Impress your friends with five fast facts about Berenice Abbott (1898–1991). NMWA’s collection includes 20 of Abbott’s photographs of people and places taken between 1925 and 1954.

1. Picturing Progress

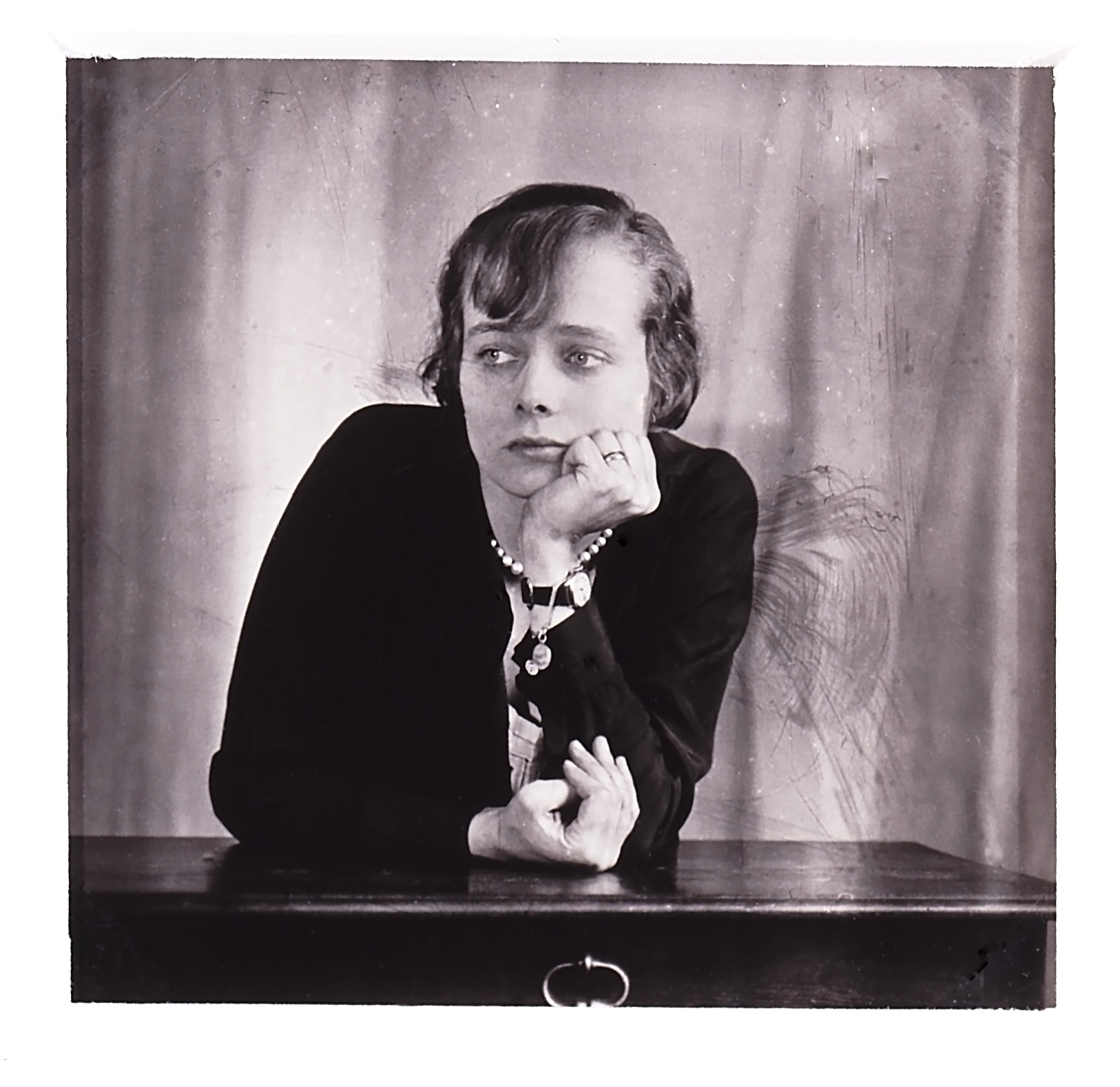

In 1920s Paris, Abbott became a sought-after photographer of progressive American women expatriates, including gallerist and artist Betty Parsons (1900–1982); Djuna Barnes (1892–1982), author of the lesbian cult classic Nightwood (1936); and poet Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892–1950), who coined the phrase “burn the candle at both ends.”

2. Government Support and Suspicion

Abbott completed Changing New York (1939), now considered the quintessential photographic record of 1930s New York City with funding from the Federal Art Project. Art critic Elizabeth McCausland (1899–1965), Abbott’s life partner, contributed text. In 1951, the FBI placed Abbott under surveillance as a “concealed communist” with “homosexual tendencies.”

3. What’s Your Angle?

Abbott captured NYC’s highs and lows. She perched atop the newly completed Empire State Building and climbed into the depths of construction excavation for Rockefeller Center. She pictured struggling storefronts and shantytowns during the Great Depression with the same reverence as posh hotels and private residences. Take a virtual tour of NYC to explore the locations of photographs in NMWA’s collection.

In the spirit of Abbott’s effort to document NYC during a tumultuous time, the Museum of the City of New York launched #CovidStoriesNYC so that New Yorkers can share their pandemic experiences first-hand.

4. Magnetic Connection

In the 1950s, Abbott created new photographic images depicting various principles of physical science, such as electromagnetism, and called this work “super sight.” Another NMWA artist, Mildred Thompson (1936–2003), similarly fascinated by that which we can’t see with the naked eye, executed a series of “Magnetic Fields” paintings in the 1990s.

5. Patently Phenomenal

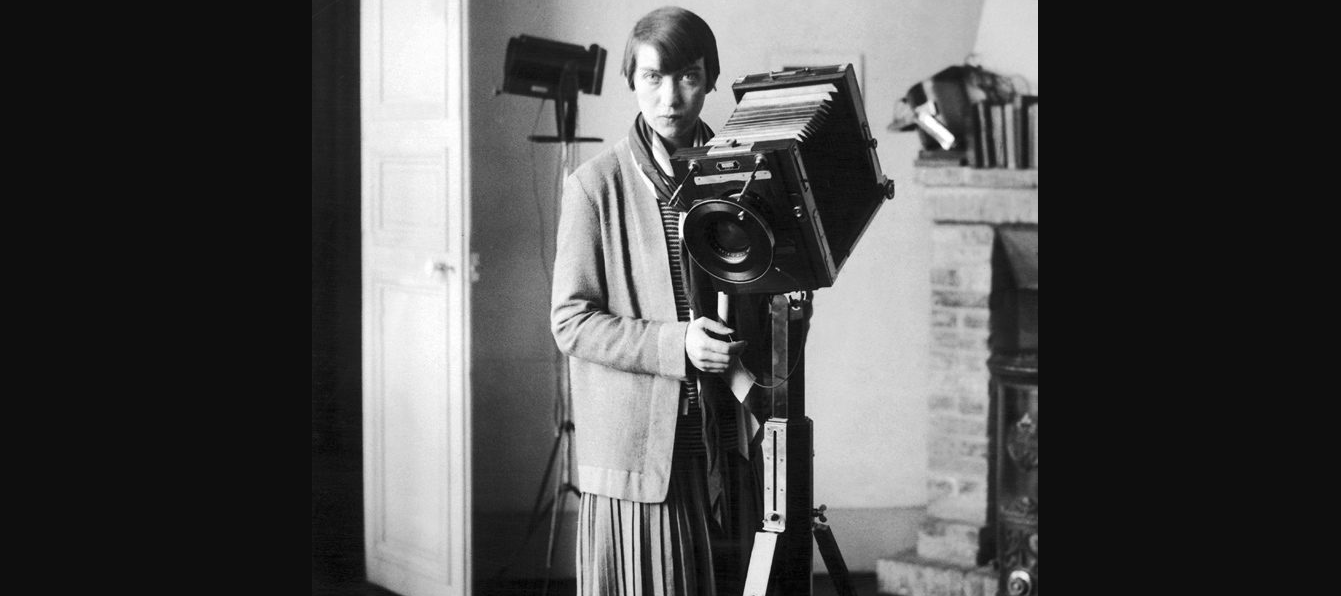

In addition to photographing creative people, changing cities, and scientific phenomena, Abbott experimented and invented. She received four U.S. patents for equipment that evolved her craft. The Distorting Easel, for instance, allowed for the manipulation of the surface that holds light-sensitive paper during development to create surreal images like this self-portrait.