In a celebration of high jinks and jokes, take a look at pranksters in NMWA’s collection. Among art tricksters’ tools of deception are optical illusions, unconventional materials, and trompe l’oeil techniques.

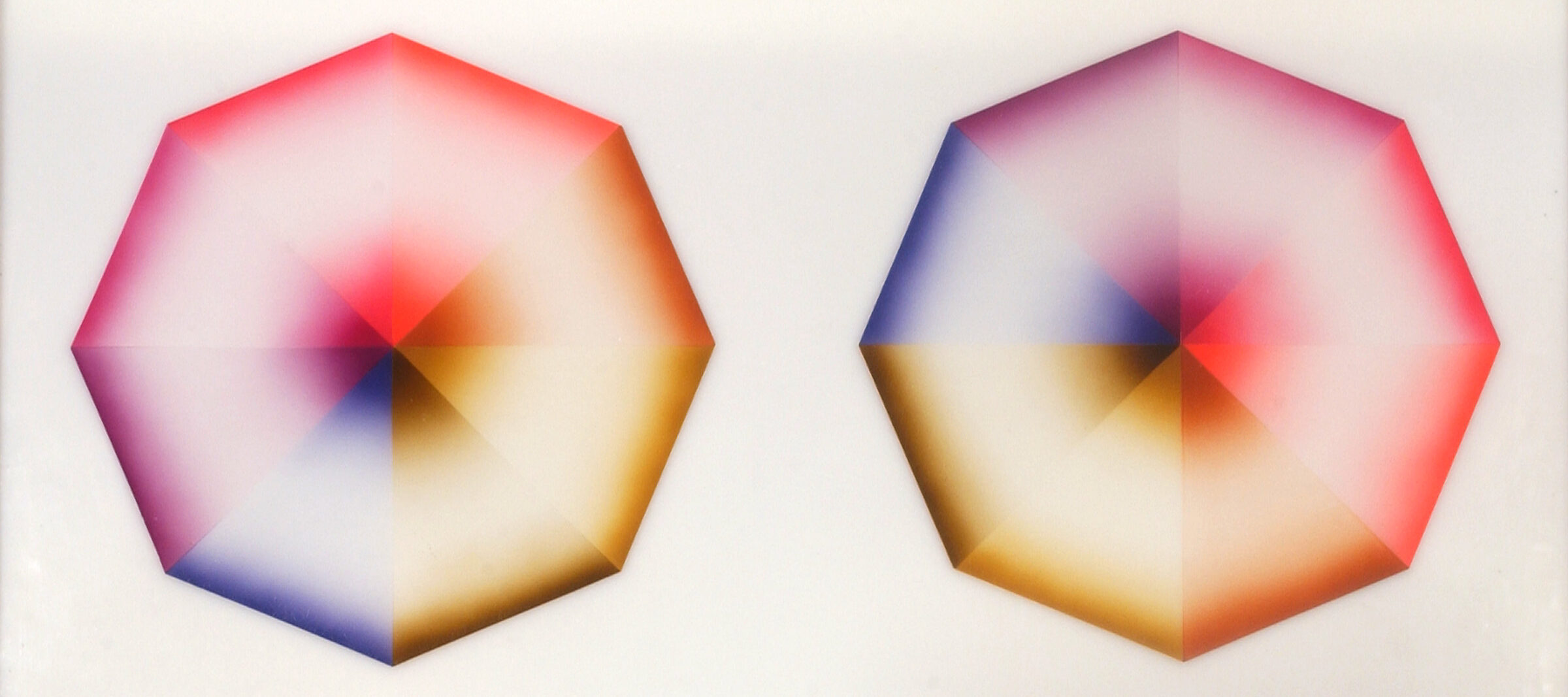

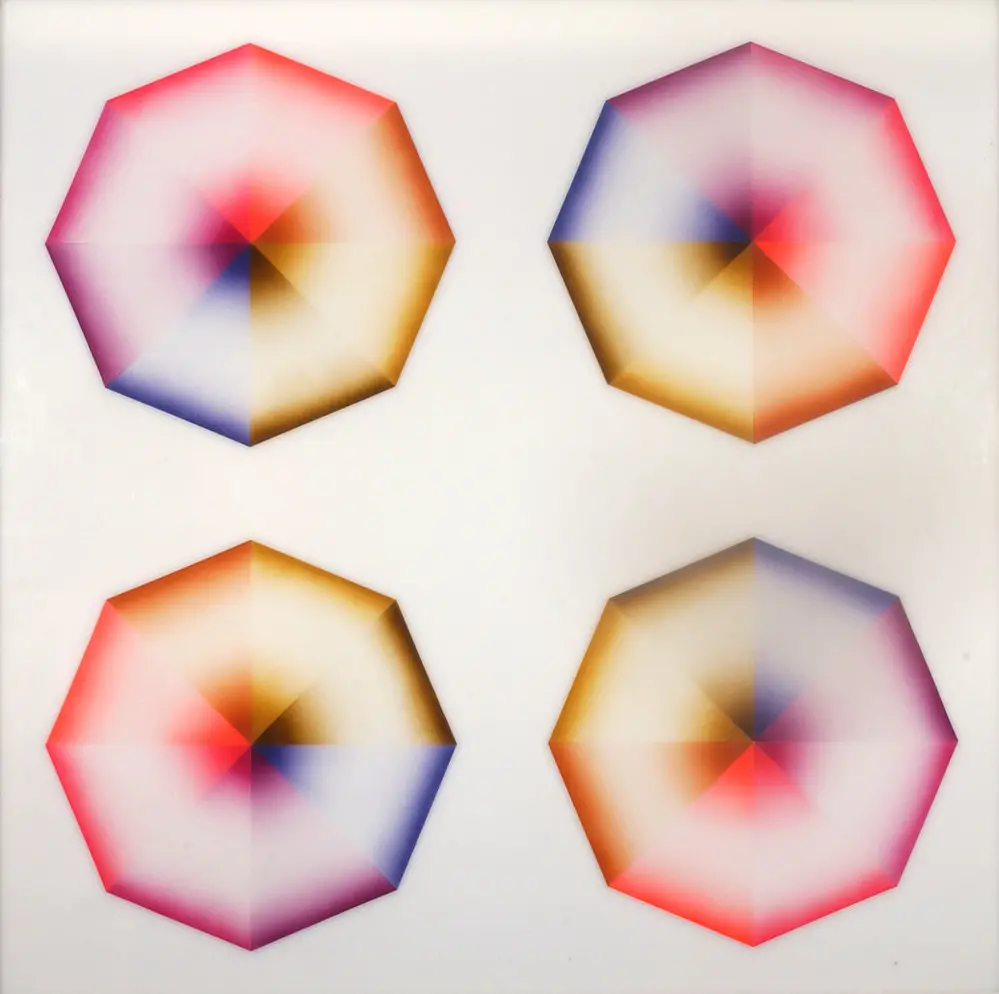

Viewers may see a brown square in the center of Judy Chicago’s vibrant Pasadena Lifesavers Red #5, although none truly exists.

Gestalt theory explains that the human brain has a tendency to create a “whole” image from individual elements. Instead of seeing only the four octagonal shapes, the human mind perceives a brown square, thus linking the separate pieces together.

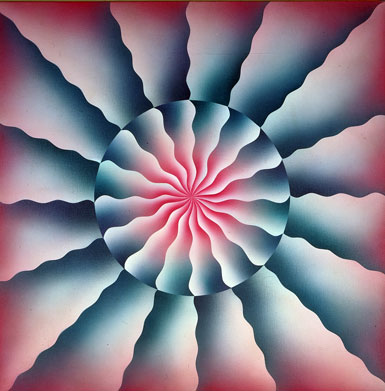

Another perceptual puzzle is Chicago’s Queen Victoria. The colorful spiraled circle at the center of the composition appears to move, creating a dizzying effect.

A variation of the “Rotating Snakes” illusion, this painting’s apparent motion is seen in an observer’s peripheral vision. The illusion is strongest when the design contains repetitive color gradations that follow curved edges. This illusion adds to the painting’s dynamism, making it more mesmerizing than disorienting.

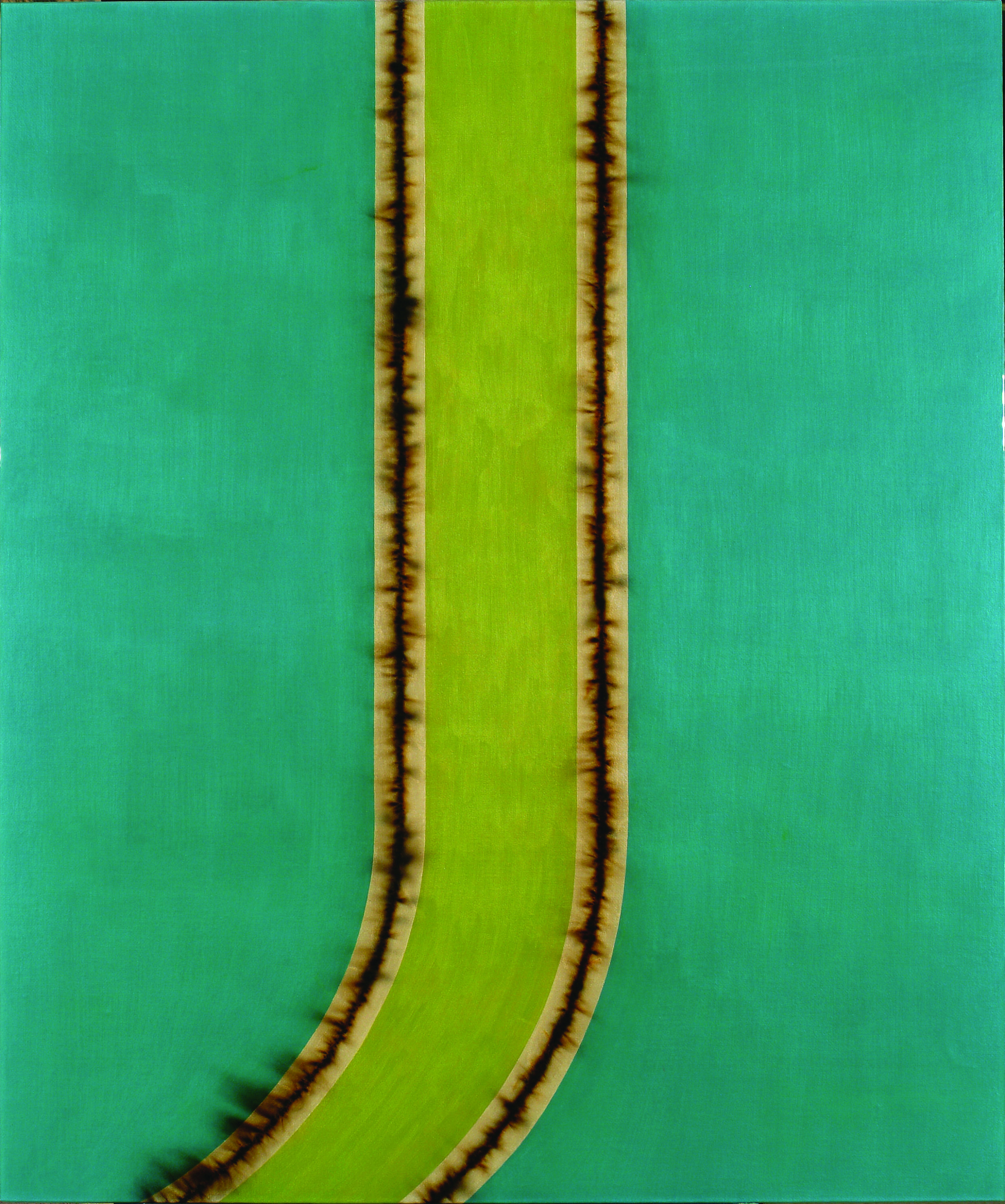

Another deceptive work is L.C. Armstrong’s Blue Shift. Not an optical illusion in the traditional sense, this work’s surprise lies in its medium.

Armstrong’s composition may simply seem like a nonobjective painting, but the artist’s materials include acrylic paint, synthetic resin, birch plywood—and a bomb fuse. In her artistic process, Armstrong first ignites the bomb fuse and then encases the piece in resin. While Armstrong can control the placement of the fuse, she cannot predict how it will mark the surface. Among her other explosive works are paintings of flowers, in which she uses bomb fuses as stems.

NMWA’s collection also contains several trompe l’oeil still-life paintings, which involve realistic imagery to create the illusion that the depicted objects are 3D. Trompe l’oeil literally translates to “tricks the eye.” Among NMWA’s illusory works are the floral still-lifes of Rachel Ruysch and Claude Raguet Hirst’s A Gentleman’s Table.

Which other visually striking works pose a cognitive conundrum?