While the 1960s resonate in the American cultural memory as a divisive and turbulent era, prevalent trends in contemporary art at the time offered very little indication of this national upheaval. Instead, Pop artists rose to prominence painting comics and consumer products, and Minimalists sanitized their works, eschewing emotional appeal and focusing strictly on formal elements. Instead of conforming to the abstract trend, Faith Ringgold directly engaged with the social and political shifts of the 1960s and 1970s, resolute in her belief that “artists have the job of documenting their times.”

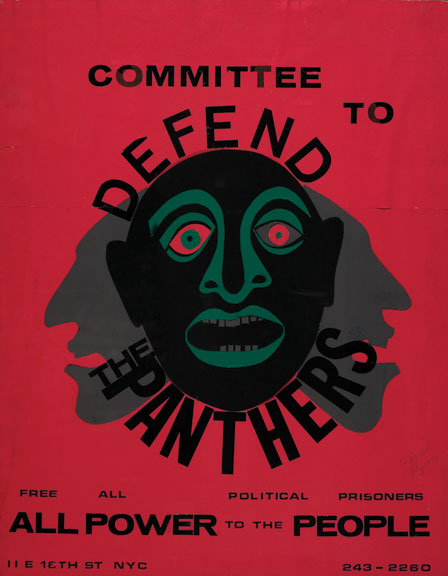

By the late 1960s, the struggle for Civil Rights had intensified. The movement’s leader, Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in 1968, and divergent political groups emerged, including those advocating “Black Power.” Faith Ringgold designed several political posters specifically for the Black Panther Party in New York.

The increasingly radical direction of several political groups, the rise of a youth “counterculture,” and widespread protest over U.S. military involvement in Vietnam all contributed to the era’s contentious atmosphere. In one such landmark instance of violence in September 1971, prisoners began to riot at the Attica Correctional Facility, a prison in upstate New York. The inmates took control of the penitentiary, demanding better conditions. Eventually, 40 people—prisoners, guards, and civilians—were killed when police stormed the facility. This unprecedented outbreak illustrated the incendiary cultural environment, causing Faith Ringgold to reflect on how violence weaved itself into the fabric of American culture.

In her political poster United States of Attica (1971–2), Ringgold presents a map of the United States that locates and enumerates riots, murders, and wars, tangibly documenting casualties of hate and violence. A fascinatingly rich and disturbing tapestry, the artist wrote in each atrocity by location, and invited viewers to do the same. Very few empty spaces exist on this map of the nation’s then-200 year history. Even the first part of the title, “United States,” seems a contradiction, with the flag divided into four parts and all available space used to record instances of disharmony and destruction. Rather than red, white, and blue, Ringgold composed her map of red and green, reminiscent of Marcus Garvey’s Black Nationalist Flag.

United States of Attica was Faith Ringgold’s most widely distributed political poster of the 1970s. Like her American People and Black Light series, the artist grappled with contemporary issues of race, identity, and violence. However, reinforcing the spirit of another poster displayed in the exhibition, “All power to the people,” Ringgold used this medium to reach a wider audience, people who would be responsive and reactive to her message. Through shifting her focus to producing political posters in the early 1970s, Ringgold was not only able to showcase societal problems, but also to encourage awareness and dialogue to begin the work of solving them.