(Click here for Part 1 of 2!)

On view at NMWA through November 10, in Awake in the Dream World, Audrey Niffenegger’s work includes an array of fantastical, surreal, and dreamlike creatures. One of Niffenegger’s artistic and conceptual predecessors highly renowned for his creation of grotesque fantasy creatures was early Renaissance Netherlandish painter Hieronymus Bosch (1450–1516), best known for his larger-than-life triptych Garden of Earthly Delights, 1503–04. The three panels of the triptych depict a strange and horrifying realm vacillating between heaven and hell. Bizarre creatures and inexplicable behaviors symbolize the follies and excesses that lead humankind to perdition. Of particular interest are Bosch’s monstrous hybrid creations that seem ahead of their time, perhaps more appropriate in the pages of a fantasy novel like The Lord of the Rings than on the canvas of an early Renaissance painter.

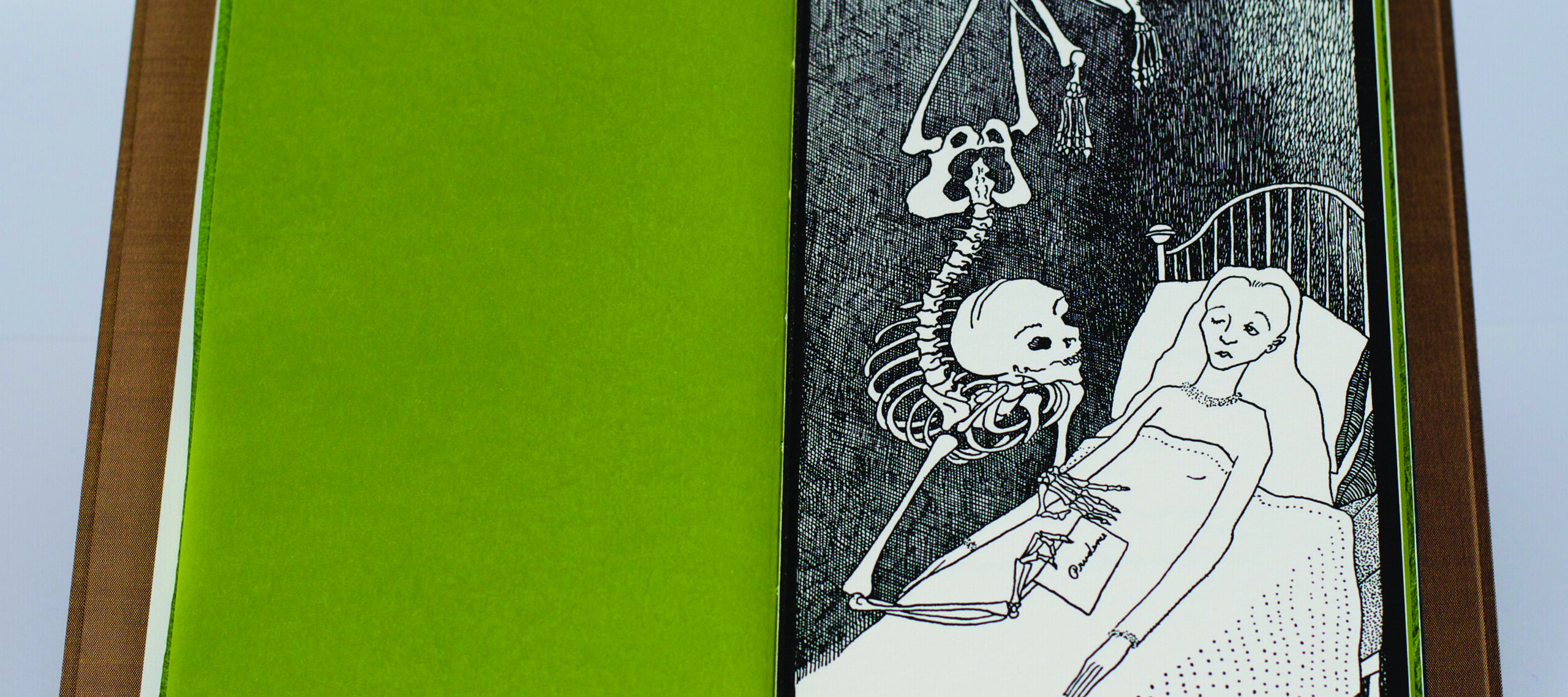

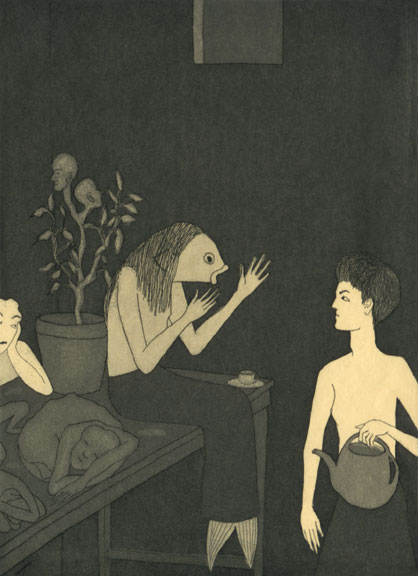

One major difference between the hybrids of Niffenegger and Bosch is that Niffenegger’s generally combine parts of familiar objects and creatures that exist in nature, like the Raven Girl, or the ghoulish, half-fish, half-human featured in Niffenegger’s first visual novel, The Adventuress (1983–85). While the appearance of both these beings is initially startling, they become less terrifying once visually dissected to reveal ordinary body and animal parts combined in curious ways. On the other end of the spectrum, Bosch’s demonic creations are often entirely unfamiliar beings with terrifyingly unfamiliar characteristics, as seen in a detail from Garden of Earthly Delights, wherein a monstrous, alien being torments a damned human. No feature of the creature is immediately recognizable, thus becoming a tool by which Bosch shocked viewers into a frightened state in order to convey his deeply held beliefs regarding mortality and the potential damnation of human souls.

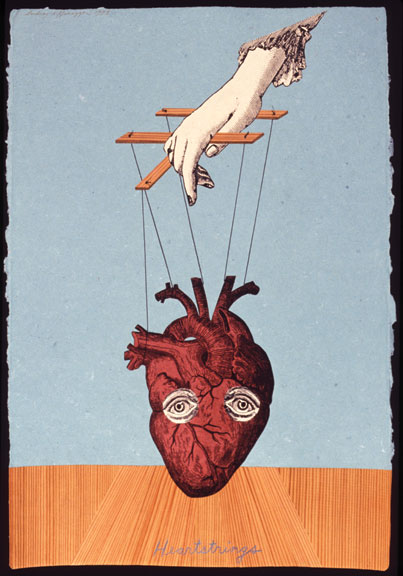

Niffenegger’s method of combining recognizable elements found in nature to create shocking juxtapositions more closely follows the tradition of René Magritte (1898–1967), a painter and adherent (along with Sigmund Freud, André Breton, and Salvador Dalí) of the early-20th-century Surrealist movement. As a Surrealist, Magritte espoused the portrayal of off-putting, illogical scenes and figures in an attempt to express the newly minted notion of the unconscious and to comment on the supposed absurdity and incongruence of life. Magritte’s methods were unique for his time because they attempted to portray the unfamiliar with familiar objects. Instead of shocking his viewers with entirely fantastical creatures, like Bosch, Magritte produced startling relationships among ordinary objects that “would practically shriek at being together” (Dubnick 409).

In L’invention Collective, 1934, Magritte combines a woman’s legs and a fish into one peculiar figure. However ridiculous the legs/fish hybrid may be, the fish and the legs still retain their individual familiarity. In Magritte’s 1934 Le Viol (The Rape), shock value is momentarily delayed as the viewer observes what appears to be a close-up of a woman’s facial features; after a quick investigation, however, a naked female torso emerges, with breasts serving as eyes, and a pubic triangle as a mouth. In such images Magritte’s intent was not to relay a specific message, like Bosch’s heralds of impending damnation; instead, they call attention to the viewer’s futile longing to have his paintings, and life, make sense. Niffenegger’s hybrid creatures similarly shock and direct viewers’ attention to the strangeness inherent in nature and dreams.

Another powerful Surrealist influence on Niffenegger is the magical and mystical work of Remedios Varo (1908–1963). As NMWA curator Krystyna Wasserman states, “Both artists inhabit imaginary realms ruled by magic; both are fascinated by animals, birds, and insects; and both depict hybrid creatures in unstable, atmospheric worlds” (Page 16 catalogue). Known for the enigmatic locations and figures portrayed in her work, Varo often painted grisly hybrids that combine semi-recognizable features from animals and humans (such as Fantastic Beast, 1959). In doing so, both Varo and Niffenegger, as well as their artistic forerunners, embody powerful messages in their work and draw viewers into shadowy dream worlds.

Works Cited:

Randa Dubnick, “Visible Poetry: Metaphor and Metonymy in the Paintings of René Magritte.” Contemporary Literature 21, 3 (1980): 407–419.

Exhibition catalogue for Awake in the Dream World: The Art of Audrey Niffenegger; Audrey Niffenegger, Krystyna Wasserman, and Mark Pascale, 2013.