Unknown artist, Canteen, mid-13th century. Syria or Northern Iraq; Brass with silver inlay, 17 3/4 x 8 1/2 x 8 1/2 in.; Freer and Sackler Galleries; inv. F1941.10

Found throughout Europe and dating mostly to the Middle Ages, historical “Black Madonnas”, such as The Virgin of Montserrat from the Monastery of Santa Maria de Montserrat in Spain, were often ascribed miraculous powers. The cause of the dark skin varies in each case. Scientific analyses on The Virgin of Montserrat reveal that the original color of the wood darkened over time. The sculpture has been subsequently repainted black throughout the centuries.

Unknown artist, The Virgin of Montserrat, also known as La Moreneta, 12th century; Polychromed wood, 37 1/2 in.; Monastery of Santa Maria de Montserrat, Spain; Photograph: Album/Art Resource, NY

This 12th century canteen from the Freer and Sackler Galleries was produced in the Middle East. The canteen features at its center an image of the enthroned Madonna and Child, surrounded by scenes from the life of Christ. Aside from Jesus, Mary is depicted most often, appearing three times on the front.

Unknown artist, Canteen, mid-13th century. Syria or Northern Iraq; Brass with silver inlay, 17 3/4 x 8 1/2 x 8 1/2 in.; Freer and Sackler Galleries; inv. F1941.10

Like the Virgin Mary, the Buddhist divinity Guanyin (known in Japan as Kannon) is often portrayed holding a child, as seen in this porcelain piece from the Peabody Essex Museum. As trade with Europe increased during the 17th century, artisans in China began modifying Guanyin figures to represent the Madonna and Child. They added a crucifix to the woman’s chest and positioned the child’s hand in a gesture of benediction.

Unknown artist, Madonna and Child, 1690–1710; Porcelain, 15 x 3 1/2 x 3 in.; Peabody Essex Museum; Museum Purchase, 2001; inv. AE85957

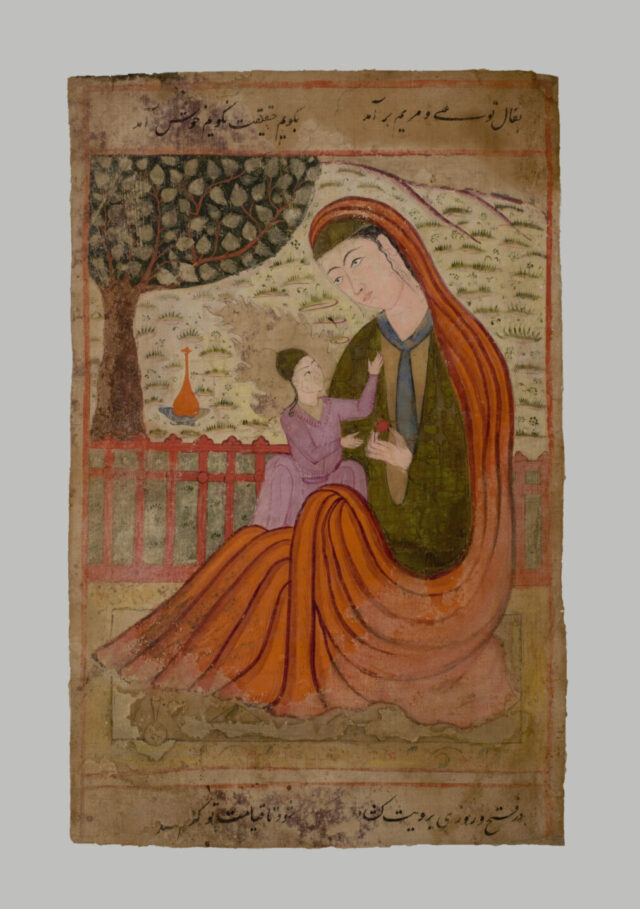

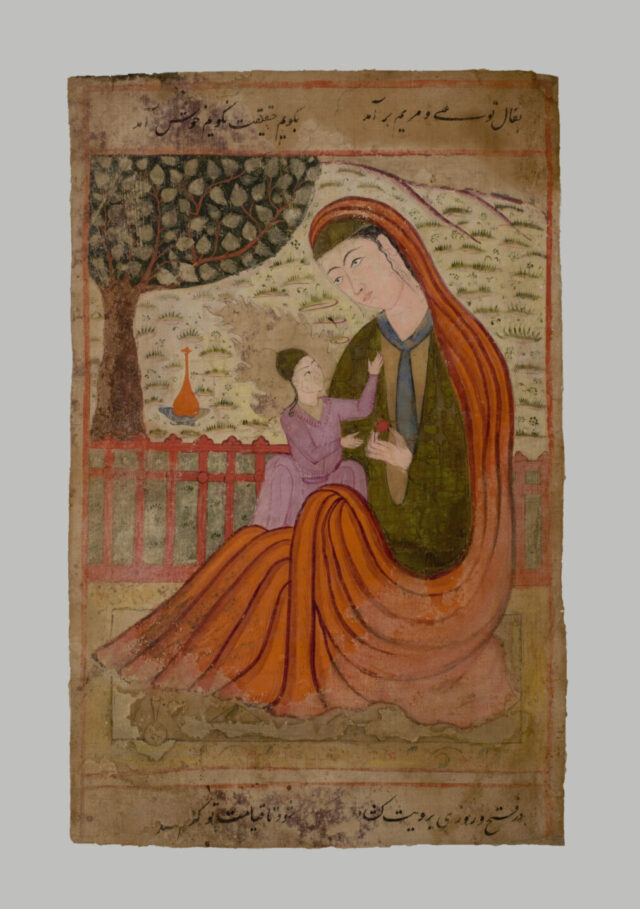

Unknown artist, Virgin Mary and Baby Jesus from a Falnama (Book of Divination) Manuscript, ca. 1600; Gouache on cloth, 13 x 8 1/3 in.; Courtesy of Sam Fogg, London

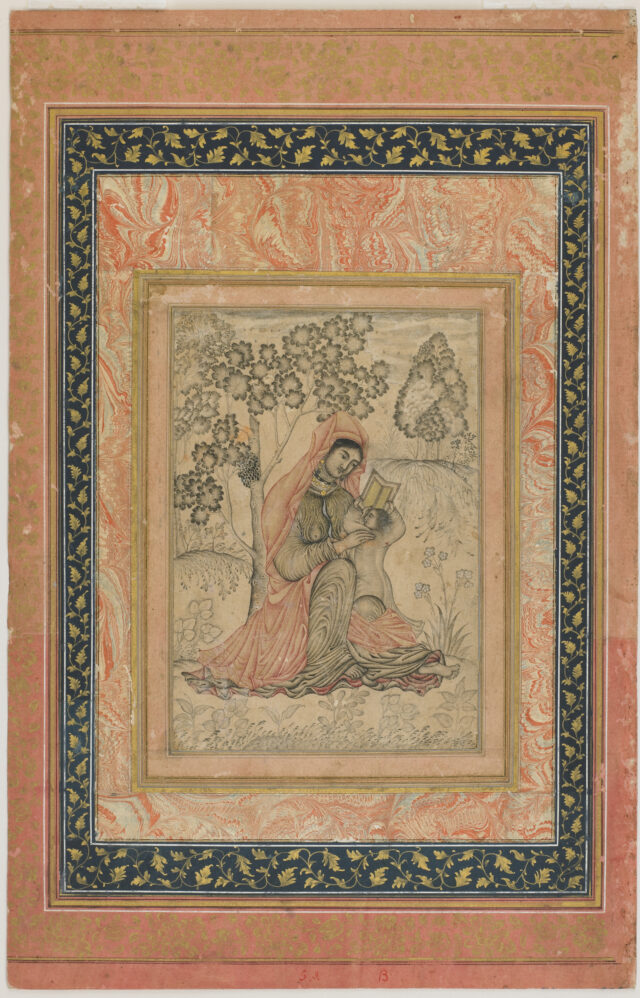

The celebrated artist Farrukh Beg likely based his image, The Madonna and Child, on a European print, which rulers of the Islamic Mughal Empire collected in quantity. While the subject is Christian, the artist’s depiction of the Madonna and Child reflects the aesthetic traditions of Indian art.

Farrukh Beg, The Madonna and Child, ca. 1605–10; Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 6 3/8 x 4 3/8 in.; Freer and Sackler Galleries; inv. F1907.155

Luisa Roldan learned her craft in her father’s sculpture studio and was appointed court sculptor in 1692 by King Charles II of Spain. In the tradition of Spanish polychrome sculpture, Roldan imbued her figures with a life-like quality through convincing flesh tones and tender interaction between mother and baby.

Luisa Roldan (La Roldana), Nursing Madonna, 17th century; Painted terracotta, 15 in. high; Private Collection, Madrid; Photograph: Album/Art Resource, NY

Falnama manuscripts were books used for divination throughout the 16th-century Islamic world. They contain images that refer to the Qur’an, the Bible, and Islamic legends. The Persian inscription on this page reads, “Jesus and Mary have been drawn as your lot, I speak the truth, I do not speak flattery: the door of conquest and fortune has been opened in front of your face.”

Unknown artist, Virgin Mary and Baby Jesus from a Falnama (Book of Divination) Manuscript, ca. 1600; Gouache on cloth, 13 x 8 1/3 in.; Courtesy of Sam Fogg, London

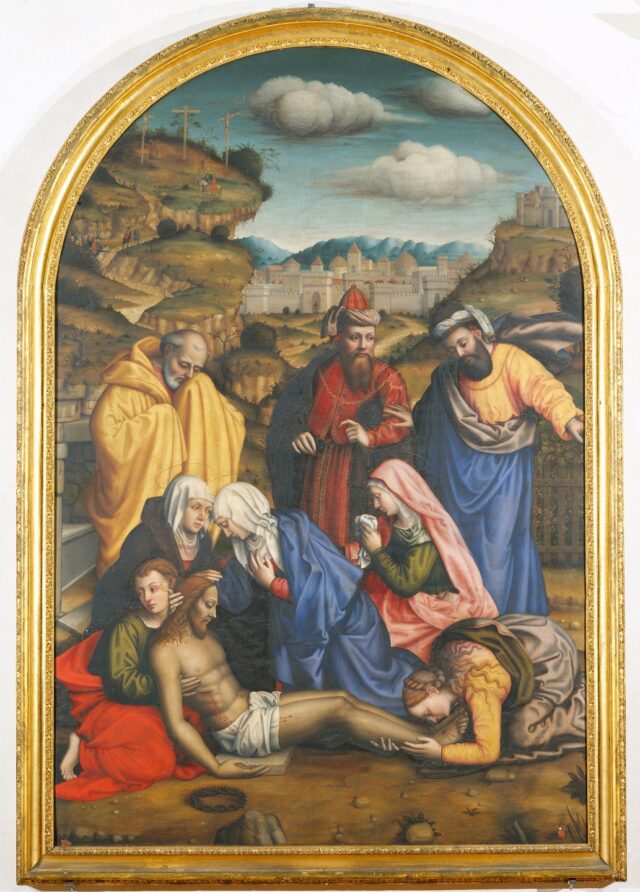

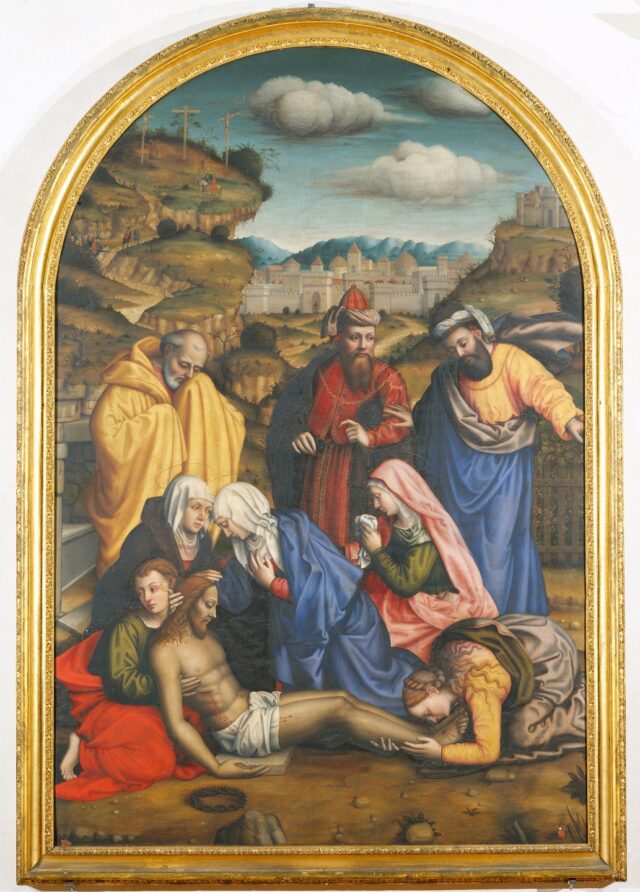

Suor Plautilla Nelli, Lamentation of Christ, 1550; Oil on panel, 113 3/8 x 75 1/2 in.; Convent of San Marco, Florence

Typical of Andean painting during the colonial period, this image, Our Lady of Sorrows from the Joslyn Art Museum, displays Mary in a stage-like setting. The pyramidal form of Mary’s cloak, a common element in these paintings, evokes the shape of the mountains in this region. It also relates her to Pachamama, the indigenous female earth deity.

Unknown artist, Our Lady of Sorrows, 19th century; Oil on canvas, 32 3/4 x 23 3/4 in.; Joslyn Art Museum; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Fred Lowell; inv. 1964.113

Suor (Sister) Plautilla Nelli was a nun and artist in Renaissance Florence. She painted this scene of the Lamentation of Christ to hang over the altar in her convent. Rather than accentuating Mary’s grief alone, Nelli emphasized the collective grief of the women gathered around Christ’s body. Although their gestures are restrained, their reddened eyes and streaming tears communicate their sorrow.

Suor Plautilla Nelli, Lamentation of Christ, 1550; Oil on panel, 113 3/8 x 75 1/2 in.; Convent of San Marco, Florence

This truncated sculpture, Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows, is startling because it lacks the costume that once adorned it. However, even when clothed and veiled, this representation of Mary’s grief over the loss of her son would have been riveting. Her mournful expression and realistic tears, along with the anatomically approximated heart, convey her visceral pain.

Unknown artist, Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows, 18th century; Polychromed wood, 17 3/4 x 17 3/4 x 9 3/4 in.; Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels

Unknown artist, Virgin of Quito, ca. 1750; Paint, wood, gold, and silver, 18 in. high; Denver Art Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John Pogzeba; inv. 1974.265

Likely made for home veneration, this portable folk art panel (retablo) from the Smithsonian American Art Museum depicts a solemn, prayerful Virgin known as Our Lady of Guadalupe. Her image, said to have miraculously appeared on the cloak of a newly converted Mexican shepherd in 1531, has enduring significance in the lives of Catholic Mexicans. Fresquís combined European Immaculate Conception imagery such as a blue mantle, halo, and crescent moon, with indigenous materials to create a humble work that resonates with local worshipers.

Pedro Antonio Fresquís, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe), ca. 1780–1830; Water-based paint on wood, 18 5/8 x 10 3/4 x 7/8 in.; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; inv. 1986.65.113

First created by Ecuadorian sculptor Bernardo de Legarda in 1734, the Virgin of Quito became a prevalent, culturally specific representation of Mary. Also called Dancing Madonna, the artwork is distinguished from more static European Madonnas through active gestures. The popularity of Legarda’s work spurred artists throughout the northern Andes to create countless replicas. Today, the largest of these overlooks Quito from a high hilltop, El Panecillo. This dynamic piece from the Denver Art Museum portrays a resolute Virgin Mary battling a serpent-like Satan.

Unknown artist, Virgin of Quito, ca. 1750; Paint, wood, gold, and silver, 18 in. high; Denver Art Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John Pogzeba; inv. 1974.265

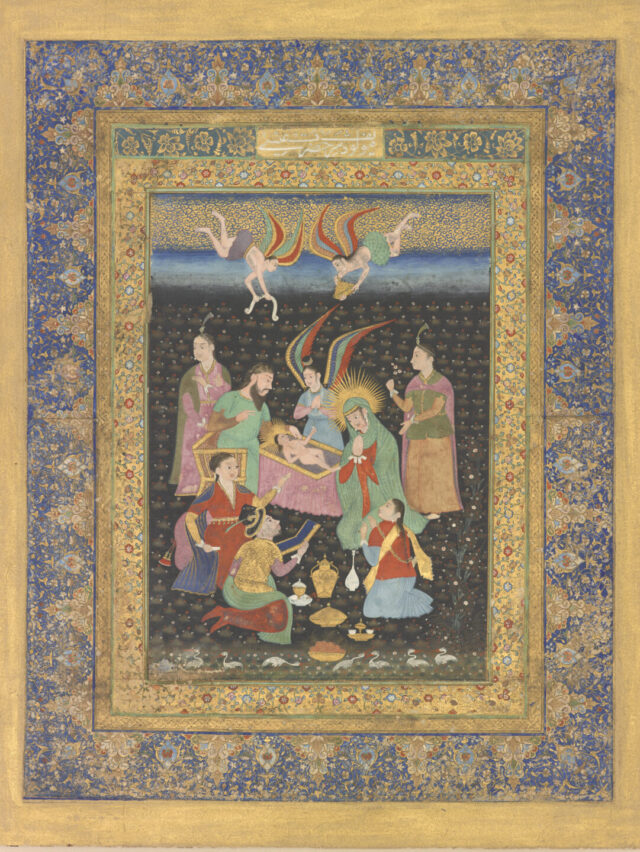

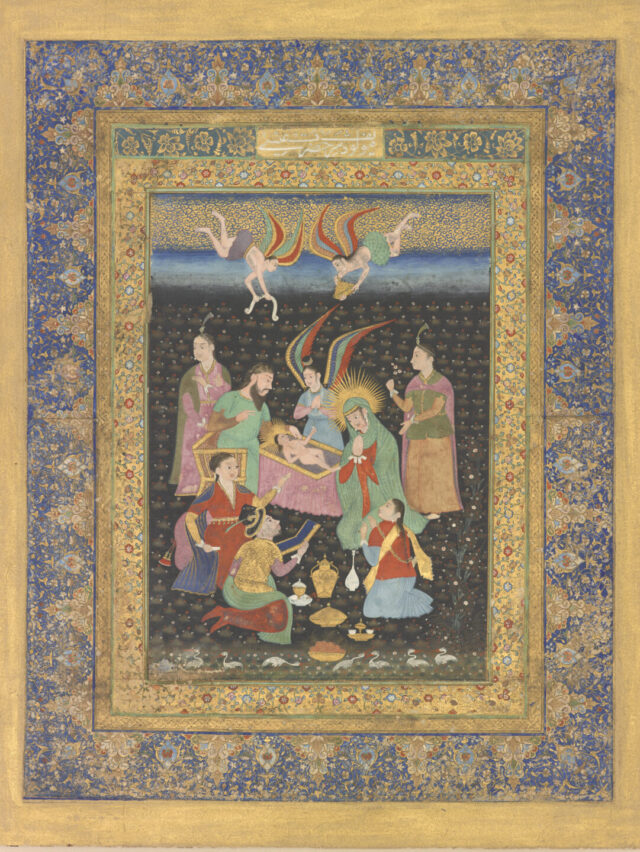

Unknown artist, Adoration of the Christ Child, ca. 1630; Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 6 1/8 x 4 3/8 in.; Freer and Sackler Galleries; inv. F1907.267

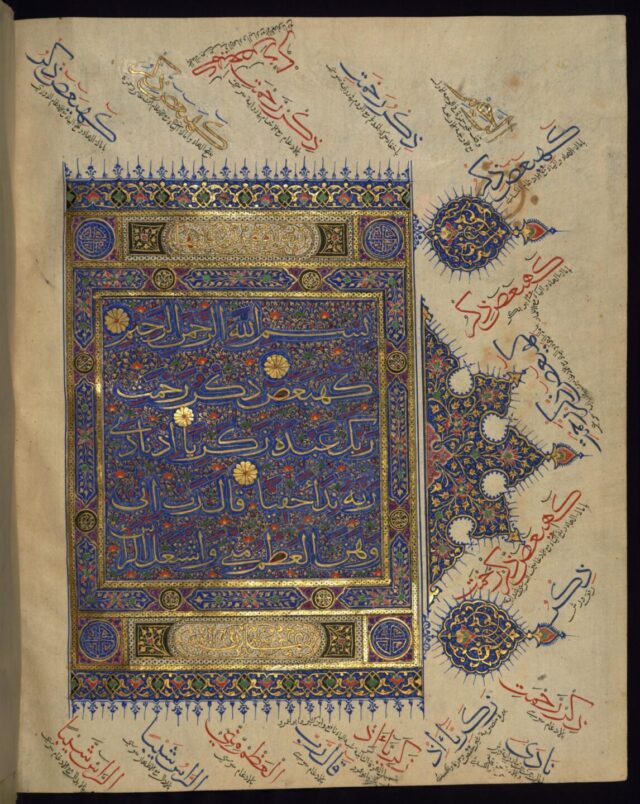

This is the second of two title pages from the “Surat Maryam,” a chapter on the Virgin Mary found in the Qur’an. Mary is a revered figure in Islam, and she is the only woman to have a chapter named after her. She is hailed as the most perfect woman in all creation; a paradigm of purity, righteousness, and obedience to God.

Unknown artist, Chapter 19 of Qur’an (Surat Maryam), 15th century; Ink and pigments on thin laid paper, 15 3/4 x 12 3/16 in.; Walters Art Museum; inv. W.563.274B

When the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier traveled to the Indian subcontinent in the 16th century, he and his followers brought with them many images of Mary, the patron saint of the Jesuits. Local artists freely interpreted Christian scenes, such as the Nativity seen here, and created vibrant compositions.

Unknown artist, Adoration of the Christ Child, ca. 1630; Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 6 1/8 x 4 3/8 in.; Freer and Sackler Galleries; inv. F1907.267

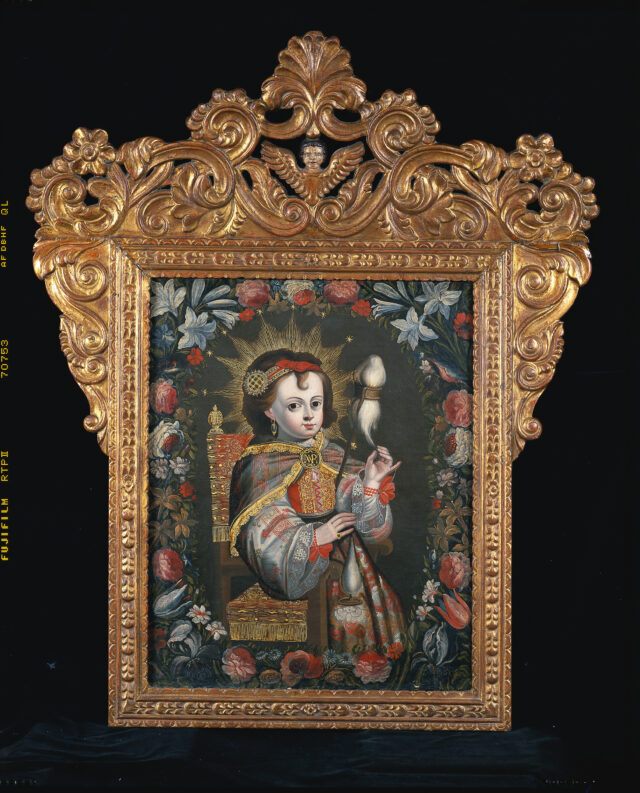

Images of the child Mary spinning wool using a typical Andean spindle intertwine European symbols with local ones. By portraying Mary in the act of spinning, the artist associates her with native Chosen Women, who were selected to make garments for the Inka king.

Unknown artist, The Child Mary Spinning, 18th century; Oil on canvas with period frame, 31 1/8 x 24 7/8 in.; Carl and Marilynn Thoma Collection

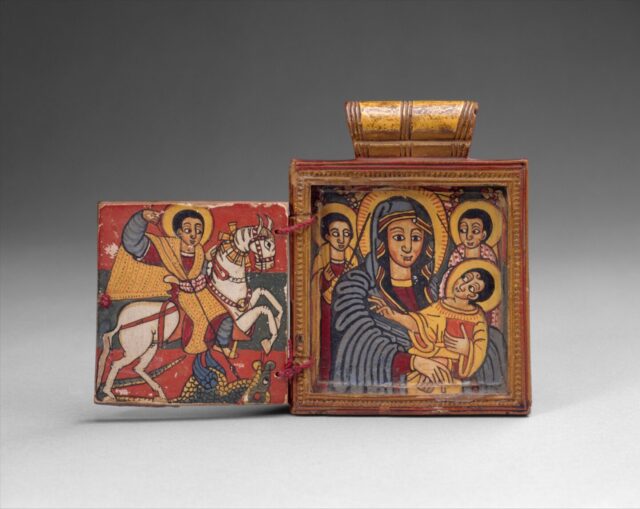

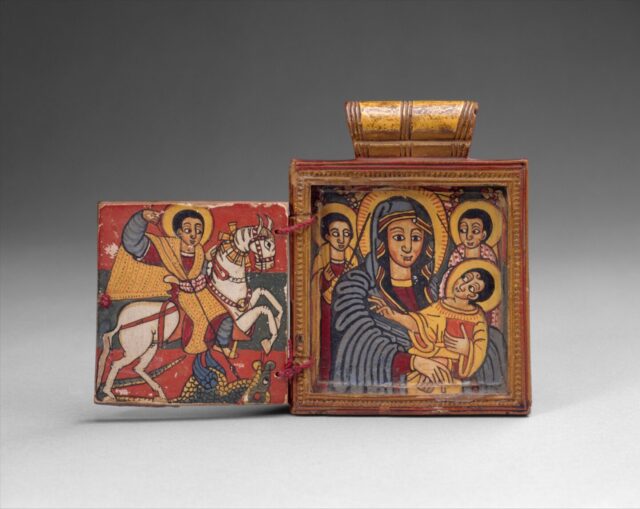

Unknown artist, Pendant Icon, 17th–18th century; Wood and tempera paint, 3 3/4 x 2 3/4 in.; Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund; inv. 1997.81.1

A nun in New Spain (now Mexico) would have worn this embroidered emblem on the shoulder of her cloak. It depicts the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, the patron saint of the nun’s monastic order, the Conceptionists. Through this object, the nun displayed not only her dedication to Mary but also her embroidery skill.

Unknown artist, Nun’s Emblem, 18th century; Silk and silver thread embroidery, 7 in. diameter; Franz Mayer Collection

Christianity flourished in Ethiopia as early as the 4th century and is still the dominant religion today. From the 15th century, Mary was a major figure in Ethiopian Christianity. Her role as an intercessor between the faithful and Jesus was reflected in numerous images. This 17th–18th century amulet from Metropolitan Museum of Art, worn around the neck, demonstrates the personal connection to Mary that many believers felt.

Unknown artist, Pendant Icon, 17th–18th century; Wood and tempera paint, 3 3/4 x 2 3/4 in.; Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund; inv. 1997.81.1

After Europeans were barred from Japan in the 1560s, those Japanese who had converted to Christianity were persecuted. Many became “hidden Christians,” practicing their faith in secret. Small statues, such as this one from Missions Etrangères Paris, were used as covert devotional aides. Outwardly they resemble the Buddhist divinity of compassion, Kannon (known in China as Guanyin), but they were venerated as the Virgin Mary and often incorporated hidden or disguised crucifixes.

Unknown artist, Statuette of Virgin Mary Disguised as Goddess Kannon, 18th–19th century; Missions Etrangères Paris; Photograph: Gianni Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY

Image permissions were supplied by the artworks’ institutions and collections.

The following are additional credits:

Creative Commons: Virgin of the Immaculate Conception (Brooklyn Museum), Virgin of the Immaculate Conception (Walters Art Museum), and Chapter 19 of Qur’an (Surat Maryam) (Walters Art Museum)

Curator: Virginia Treanor

Video Producer: Dorothea Trufelman

Editor: Elizabeth Lynch

Project Manager: Laura Hoffman

Production Coordinator: Traci Christensen

@ 2014 National Museum of Women in the Arts

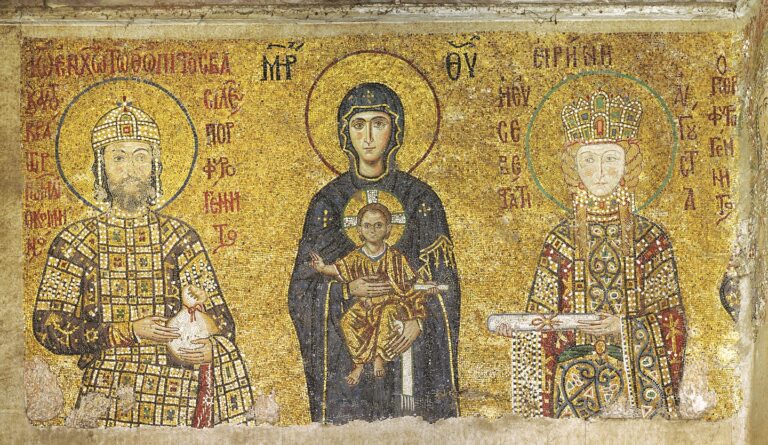

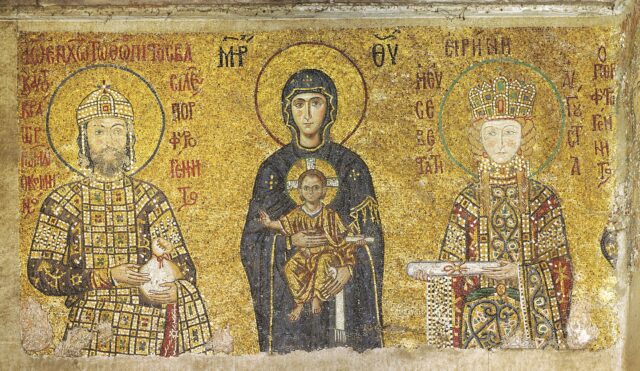

Unknown artist, Madonna and Child, flanked by Empress Irene and Emperor John II Komnenos (detail), 12th century; Turkey; Mosaic; Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, Turkey; Photograph: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York