Remix: The Collection

NMWA’s collection holds more than 6,000 works of art dating from the late sixteenth century through today. Made by women and nonbinary artists from six continents, these paintings, prints, photo-based works, and sculptures demonstrate an exceptional range of approaches and mediums.

The museum shares its collection in thematic groupings rather than chronological order. Historical and contemporary works are groups together around fundamental topics. This presentation emphasizes themes that have engaged artists across time and place as well as each maker’s distinctive viewpoint and methods. These galleries express NMWA’s powerful mission to shift conventional thinking about art and gender and write a new and ever-evolving history of art.

NMWA’s “Create Connections” digital kiosk, located on this floor, enriches the in-gallery experience by highlighting intriguing connections among artworks on view and inviting visitors to share personal reflections.

Remix: The Collection is organized by the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

The exhibition is sponsored by Lugano Diamonds.

Additional funding is provided by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Sue J. Henry and Carter G. Phillips Exhibition Fund, and the Clara M. Lovett Emerging Artists Fund.

The “Create Connections” interactive kiosk is produced by the National Museum of Women in the Arts in collaboration with Art Processors and is made possible through the generous support of Denise Littlefield Sobel.

Photo Credit

While photography by women has been historically underrepresented in museum collections and major exhibitions, NMWA has represented and advocated for women photographers since its founding. The photographs in this gallery offer a wider understanding of the possibilities of the medium and the ways in which artists have used photography to experience the world. Whether they depict penetrating portraits of American subcultures, dreamy landscapes and nostalgic interiors, or searing critiques of colonial narratives through ornamented, fragmented bodies, these images have the power to excite, provoke, transfix, and transport viewers.

Red Ice, 2000

Deborah Paauwe (b. 1972, West Chester, Pennsylvania)

Chromogenic color print; Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

Lather, 1998-99

Deborah Paauwe (b. 1972, West Chester, Pennsylvania)

Chromogenic color print; Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

I Listened as the World Became Silent, from the series “Bloodline—Stories of my Grandmothers | nôhkominak âcimowina,” 2022

Meryl McMaster (nêhiyaw/Métis from Red Pheasant Cree Nation and member of Siksika Nation, British, and Dutch, b. 1988, Ottawa, Canada)

Pigment print on archival paper mounted to aluminum composite panel; Gift of the Canada Committee of the National Museum of Women in the Arts

McMaster explores her Indigenous and Euro-Canadian identities through semi-fantastical self-portraits. Here, she references the 1885 hangings of eight Plains Cree men who were publicly executed for killing several government representatives during an uprising against the Canadian government for its oppression of Indigenous peoples. The artist’s great-great-grandmother may have been part of a group who were forced to witness this event as a warning against future dissent. McMaster’s fencing attire evokes resistance and protection while the butterflies—species native to Saskatchewan—signify the souls of ancestors in Cree culture.

Mrs. Longdon as Persephone, from the series “Goddesses,” 1935

Yevonde (b. 1893, London; d. 1975, London)

Pigment transfer print; Gift of Joyce and Michael Axelrod Collection

A pioneer of color photography, Yevonde (born Yevonde Philone Cumbers and also known as Madame Yevonde) experimented with the new Vivex color process in the 1930s, placing colored gels and filters over lights and her camera lens. In 1935, inspired by the Olympian Ball, a costume charity gala at Claridge’s Hotel in London, Yevonde photographed fashionable society women dressed as figures from Greek mythology. Modifying the costumes, props, and lighting to her specifications, Yevonde set out to establish color photography as a critical medium for portraiture.

Escape Artist (Primary Colours), 2008

Sam Taylor-Johnson (b. 1967, Croydon, United Kingdom)

Chromogenic color print; Gift of Tony and Trisja Podesta Collection

Escape Artist is part of a series of photographs made in response to the artist’s personal battle with cancer. Taylor-Johnson said, “I have to hide my face in the pictures. It is a combination of hiding the grimacing pain—because I think that destroys the photograph—but it is also because I don’t think you need to see my face.” Suspended in midair from brightly colored helium balloons, the artist alludes to a sense of physical freedom from the constraints of illness.

Ice Pedestal #1, 2000 (printed 2015)

Ice Pedestal #2, 2000 (printed 2015)

Ice Pedestal #3, 2000 (printed 2015)

Kirsten Justesen (b. 1943, Odense, Denmark)

Chromogenic color prints; Gift of Peter J. Lassen

Since the 1980s, ice has been a pivotal medium in Justesen’s practice. A pioneer of body art, Justesen explores the transient nature of ice and alludes to the human body’s own impermanence. In performances and staged photographs, Justesen poses atop massive blocks of ice, donning only black rubber boots and gloves. Through tactile encounters of her mostly naked body with the frozen pedestals, the artist investigates sculptural concerns including form, volume, and surface and considers the ways that nature and humanity act on one another.

Cuatro Pescaditos, Juchitán, Oaxaca, 1986 (printed later)

Graciela Iturbide (b. 1942, Mexico City)

Gelatin silver print; Gift of Charles and Teresa Friedlander, in honor of his mother, Jacqueline S. Friedlander

Third World Blondes Have More Money: Krystel Tiara, 2002

Daniela Rossell (b. 1973, Mexico City)

C-print; Gift of Tony and Trisja Podesta Collection

Rossell’s ongoing exploration of Mexico City’s newly wealthy class blurs divisions between society portraiture, fashion photography, and ethnographic photography. Her portraits typically depict women with significant disposable incomes who dress extravagantly, live in lavish, kitschy environments, and engage in provocative or sacrilegious behaviors. Viewers of Rossell’s work have often denounced these images of idle women, which undermine the maternal, demure, and domestic roles expected of them.

Fiber Optics

Artists often encourage us to see things in a different way. Through their work using fiber—whether thread, felt, crochet, or textiles—artists offer new perspectives on materials that surround us in our everyday lives. Historically marginalized as “women’s work,” fiber-based art has been devalued within with the gendered hierarchy of art, which places the traditionally male-dominated fields of painting and sculpture at the top. Contemporary artists who use fiber-based techniques in their work engage directly with this history: they emphasize labor-intensive methods and advocate for the value of the textile arts as a form of artistic expression.

Viriato, 2005

Joana Vasconcelos (b. 1971, Paris)

Faience dog and handmade cotton crochet; Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

Hillary, 2002

Andrea Higgins (b. 1970, Kansas City)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

Higgins layers thick brush marks to emulate the stitch- by-stitch patterns of fabric swatches, creating dynamic abstractions. Hillary is from the artist’s series “The Presidents’ Wives,” which explores the relationship between women, fashion, and power through abstractions based on the wardrobes of first ladies of the United States. The minute strokes—matte and glossy black paint over a nearly obscured pink ground—evoke the black pantsuit and pink blouse that Hillary Rodham Clinton wore to welcome incoming First Lady Laura Bush to the White House in December 2000.

The Founder, 2020

LaToya M. Hobbs (b. 1983, Little Rock, Arkansas)

Acrylic, collage, and relief carving on wood panel; Museum Purchase: Funds provided by friends of Lisa Claudy Fleischman in her memory, with additional support from the artist

In The Founder, Hobbs depicts Tanekeya Word, a Milwaukee-based artist and founder of Black Women of Print, an organization focused on promoting Black women printmakers. A textile-like pattern behind Word features a moon-in-star shape that also appears on her shirt. It is one of many emblems known as adinkra in Ghana’s Asante culture. Often found on textiles, the moon-in-star shape, nsoromma, symbolizes God watching over all people.

Jackie (India), 2003

Andrea Higgins (b. 1970, Kansas City, Missouri)

Acrylic on canvas; Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

One Night Stand, 2002

Pacita Abad (b. 1946, Basco, Philippines; d. 2004, Singapore)

Oil and batik cloth on canvas; Gift of Jack and Kristiyani Garrity

This work, part of Abad’s “Endless Blues” series, was inspired by the blues, a musical genre that powerfully and beautifully expresses life’s hardships. Abad layered many materials and techniques into her work; here, she stitched batik cloth in strips onto canvas, then painted her colorful abstract forms. Created after the September 11 attacks and her cancer diagnosis, Abad channeled the pain and beauty of life into celebratory color.

Plaid Houses (Maquettes): Blue Japan House, Blue Art Deco House, Red Deconstructivist House, White Hut, Acid Green Dome House, Brown Usha Hut, Pink Tower, Turquoise Blue Colonial House (Barbados), and Orange Breton House, 2005-11

Laure Tixier (b. 1972, Chamalières, France)

Wool, felt, and thread; Gift of Les Amis du NMWA

The Meeting of Passion and Intellect, 1981

Harmony Hammond (b. 1944, Chicago)

Mixed media; Gift of Lily Tomlin and the artist

Aiming to break down divisions between painting and sculpture, art and craft, Hammond uses an array of materials to create works such as The Meeting of Passion and Intellect, in which she wraps wooden armatures with fabric and then covers them with latex and paint. In combining textiles, traditionally associated with women, with the historically masculine realms of painting and sculpture, Hammond questions such binaries, suggested in the two halves of the work as well as its title.

American Collection #4: Jo Baker’s Bananas, 1997

Faith Ringgold (b. 1930, New York City)

Acrylic on canvas with pieced fabric border; Museum purchase: Funds provided by the Estate of Barbara Bingham Moore, Olga V. Hargis Family Trusts, and the Members’ Acquisition Fund

Ties That Bind, 2013

Sonya Clark (b. 1967, Washington, D.C.)

Wood and thread; Museum purchase: Gift of Susan Fisher Sterling

Clark, whose maternal grandmother was a tailor, uses thread in this work to stitch a map of the world onto the surface of a block of wood. Below, the individual threads are gathered and knotted together in a visualization of humanity’s interconnectedness.

Home, Maker

Throughout history, women artists have persisted despite facing barriers to formal artistic training. Obligations in the home, which fell disproportionately to women, were another obstacle in their pursuit of independent careers. Paintings, prints, and works in silver and ceramic spotlight women’s shifting domestic roles and celebrate their ever-growing agency as makers.

In particular, women silversmiths of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries often learned the trade within their families and built successful careers as designers and businesswomen. Contemporary artists confront and play on stereotypes of women as homemakers with unexpected materials and bold, witty twists on traditionally “feminine” themes. These artists sculpt, paint, and build as makers of their own futures.

Stepping Out, 2000

Elizabeth Catlett (b. 1915, Washington D.C., d. Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2012)

Bronze; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Sugar Basket, 1777

Hester Bateman (b. 1708, London; d. 1794, London)

Silver and glass; Silver collection assembled by Nancy Valentine, purchased with funds donated by Mr. and Mrs. Oliver R. Grace and Family

Cast Sugar Tongs, 18th century

Hester Bateman (b. 1708, London; d. 1794, London)

Silver; Silver collection assembled by Nancy Valentine, purchased with funds donated by Mr. and Mrs. Oliver R. Grace and Family

Berry Spoon with Griffin, 1798

Ann Bateman (b. 1748, England; d. 1813, England)

Silver; Gift of Ann Harper Bein in honor of Edna Seitz Harper

Berry Spoon, 1798

Ann Bateman (b. 1748, England; d. 1813, England)

Silver; Gift of Ann Harper Bein in honor of Edna Seitz Harper

Madame de Pompadour (née Poisson), Tea Service, 1990

Cindy Sherman (b. 1954, Glen Ridge, New Jersey)

Limoges porcelain with silkscreen and china paint; Produced by Artes Magnus; Gift of Steven Scott, Baltimore, in memory of National Museum of Women in the Arts Founder Wilhelmina Cole Holladay

Sherman fashioned this tea service set after an original 1756 design commissioned from the Manufacture Royale de Sèvres by Jeanne Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour, commonly known as Madame de Pompadour. An image of Sherman dressed as Madame de Pompadour is silkscreened onto the porcelain, along with hand-painted designs. Sherman and her collaborators produced the design in yellow (as seen here) as well as apple green, royal blue, and Pompadour pink, all traditional colors for eighteenth-century porcelain dinnerware.

A-E-I-O-U and Sometimes Y, 2009

Mickalene Thomas (b. 1971, Camden, New Jersey)

Rhinestones, acrylic, and enamel on wood panel; Gift of Deborah Carstens

Thomas explores and expands traditional notions of female identity and beauty through her bejeweled depictions of Black women. Working from a digital projection of her model, Fran, she outlined her subject’s contours in black rhinestones using chopsticks. For Thomas, rhinestones are a surrogate for the masking, dressing up, and beautifying that women often undertake. She tells her own story through photography and painting, describing her art as “a radical and revolutionary act” that rebuffs Eurocentric, male representations of Black women.

Mirror Mirror: Mulatta Seeking Inner Negress II, 2014

Alison Saar (b. 1956, Los Angeles)

Woodcut on chine collé; Promised gift of Steven Scott, Baltimore, in honor of Dr. Leslie King-Hammond, Dean Emerita of Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore

Saar’s figurative prints explore race, identity, and the many roles women hold in the home and in society. Mirror Mirror depicts a barefoot female figure from the back, her face visible only in the reflection of the frying pan in her hand. Though the work primarily explores racial identity, this perspective emphasizes how domestic work by women often goes unnoticed. Here, Saar’s use of two different flesh tones, lighter on the figure and darker in her reflection, relates to the term “mulatta” in the work’s title and the artist’s own experience as a biracial woman.

Sarah Weighing Laurie, 8 Months, 2023

Caroline Walker (b. 1982, Dunfermline, Scotland)

Oil on board; Gift of the Zakir Patel Collection, U.K.

Sarah Weighing Laurie, 4 Weeks, 2024

Caroline Walker (b. 1982, Dunfermline, Scotland)

Oil on board; Gift of the Zakir Patel Collection, U.K.

In compositions based on her own documentary photographs, Walker explores the everyday lives of women and the often-overlooked jobs they perform. These two paintings depict a visiting public health aide who weighs baby Laurie at four weeks and eight months old. These aides, common in the United Kingdom, support families of young children from pregnancy through age five. Walker’s tender portraits illustrate the way childcare and welfare are managed through both paid and unpaid labor.

Lying House, from the series “Lying Objects Print Portfolio,” 1992

Laurie Simmons (b. 1949, Queens, New York)

Off-set print (photolithograph); Gift of Steven Scott, Baltimore, in honor of the artist and the twenty-fifth anniversary of the National Museum of Women in the Arts

With dramatic lighting and distorted scale, Simmons uses dolls and miniature objects to explore domesticity, objectification, and American consumerism—in particular, the way these phenomena affect women. In Lying House, a woman (represented only by long, slim legs) and a house metamorphose into one, linking womanhood and homemaking. The photograph’s angle may also suggest that the woman is trapped beneath the house, representing the crushing constraints of domestic responsibilities.

Tupperware—Transforming a Chaotic Kitchen, 2008

Honor Freeman (b. 1978, Adelaide, South Australia)

Slip-cast porcelain; Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

Apron, 1997

Ursula von Rydingsvard (b. 1942, Deensen, Germany)

Cedar wood, stain, and graphite; Gift of Tony and Trisja Podesta Collection

SoHo Women Artists, 1977-78

May Stevens (b. 1924, Boston; d. 2019, Santa Fe, New Mexico)

Acrylic on canvas; Museum purchase: The Lois Pollard Price Acquisition Fund

Stevens created this work as a contemporary version of an academic history painting, a genre that typically excluded women as both artists and subjects. Inspired by Linda Nochlin’s 1971 essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” the painting recognizes feminist artists, thinkers, and residents of New York City’s SoHo neighborhood, where Stevens lived and worked. Pictured from left to right are Signora d’Apolito (owner of a local bakery); two men from the neighborhood’s Italian American community; Stevens herself; artists Harmony Hammond, Joyce Kozloff (with her son Nikolas), Marty Pottenger, Louise Bourgeois (in one of her wearable sculptures), and Miriam Schapiro; critic Lucy Lippard; and artist Sarah Charlesworth.

Elemental

In historical art, the female form often stands as an allegorical representation of earth or the seasons. Rejecting this conventional “muse” model, today’s artists share their clear view of earth—along with water, fire, and air—as creative tools and forces of life and purification. Carving and cutting wood or digging into the ground to make their art, artists refute gendered ideas about strength, handwork, and labor. Their impressions of snow, waterfalls, ocean waves, and tangled vines reflect their respect for the power of gravity and time. Experimenting with the substances that compose our planet, artists visualize the formidable transformative powers of humankind.

Yam Story ’96, 1996

Emily Kame Kngwarreye (Anmatyerre language group, b, 1910, Alhalkere, Australia; d. 1996, Alice Springs, Australia)

Acrylic on canvas; Gift of the Collection of Margaret Levi and Robert Kaplan

At age seventy-eight, Kngwarreye began portraying her impressions of patterns and textures in the landscape around her home. Yam Story ’96 alludes to the generative function of the earth in nurturing the pencil yam (kame), The tangled lines of red, orange, and pink may convey the yam’s twining vine or its thicket of roots and tubers snaking through the ground. Within her community’s kinship structure, Kngwarreye was a senior custodian of the yam Dreaming, the English word used to describe Indigenous Australian narratives about the creation of the universe.

Untitled (Wood Picture), ca. 1970

Mildred Thompson (b. 1936, Jacksonville, Florida; d. 2003, Atlanta)

Wood; Gift of Camille Ann Brewer in honor and memory of Mildred Thompson

Thompson confounded gendered ideas about the muscular actions of building and construction in “Wood Pictures,” her series of compositions made from machine-cut wood segments. This work has a strong rectangular structure, but the swirls and shades within each piece of wood add an organic quality. Thompson applied her deep scientific knowledge to her visual art. She observed universal patterns while also alluding to the varied rhythms that exist throughout nature, music, and architecture.

La llamada (The Call), 1961

Remedios Varo (b. 1908, Anglès, Spain; d. 1963, Mexico City)

Oil on Masonite; Gift from a private collection

Acqua Alta 3, 2010

Janaina Tschäpe (b. 1973, Munich)

Chromogenic color print; Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

Images of aquatic worlds recur across Tschäpe’s work. In her photographic series “Acqua Alta,” the city of Venice stands in for an imaginary realm floating in water and navigated by female figures wearing biomorphic costumes created by the artist. Tschäpe grew up in Brazil, and the characters she develops reflect Afro-Brazilian belief systems as well as the artist’s personal mythology, which presents the female body as a vessel for transformation.

Après la tempête (After the Storm), ca. 1876

Sarah Bernhardt (b. 1844, Paris; d. 1923, Paris)

Marble; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Waterfall of a Misty Dawn, 1990

Pat Steir (b. 1940, Newark, New Jersey)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Yuban Coffee Warehouse, Water and Dock Streets, Brooklyn, NY, 1936 (printed later)

Berenice Abbott (b. 1898, Springfield, Ohio; d. 1991, Monson, Maine)

Gelatin silver print; On loan from the Helen and Saul Levi Estate

Science (Magnetic), 1958 (printed later)

Berenice Abbott (b. 1898, Springfield, Ohio; d. 1991, Monson, Maine)

Gelatin silver print; Gift of Jordan and Devinah Finn

Best known for her documentary photographs of New York City made in the 1930s, Abbott later revolutionized the use of photography in documenting scientific phenomena. This print presents a negative image of iron filings scattered above a bar magnet and pulled into the bar’s magnetic field. In collaboration with scientists, Abbott produced images of a variety of objects—from magnets and mirrors to insects and roots—which were included in scientific textbooks.

Sale Neige, 1980

Joan Mitchell (b. 1925, Chicago; d. 1992, Paris)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Sheep Shearing, from the series “The Farmer’s Year,” 1933

Clare Leighton (b. 1898, London; d. 1989, Watertown, Connecticut)

Wood engraving on paper; Gift of Sylvia Stein

Landing, from the series “Canadian Lumber Camp,” 1931

Clare Leighton (b. 1898, London; d. 1989, Watertown, Connecticut)

Wood engraving on paper; Gift of Sylvia Stein

Jar, ca. 1939

Maria Martinez (b. 1887, San lldefonso Pueblo, New Mexico; d. 1980, San lldefonso Pueblo, New Mexico) and Julian Martinez (b. 1879, San lldefonso Pueblo, New Mexico; d. 1943, San lldefonso Pueblo, New Mexico)

Blackware; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Blackware was a style of pottery made by ancestors of the Pueblo people, but knowledge of how to create it was lost until Maria Martinez and her husband Julian perfected their process for making black-on-black pottery around 1921. Maria made this jar with clay found on her pueblo. Once she polished the dried jar with a small stone, Julian painted on the design with slip (liquid clay). They fired the pot in an outdoor pit, turning its surface black.

Seed Pot, undated

Dorothy Torivio (b. 1946, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico; d. 2011, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico)

Black-on-white pottery; Bequest of Lorna S. Jaffe

The Large Family Group, 1957

Marisol (b. 1930, Paris; d. 2016, New York City)

Painted wood; Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Gift of Mr. and Mrs. C. M. Lewis)

Kelly’s Cove, 2002

Mary Heilmann (b. 1940, San Francisco)

Etching on paper; Promised gift of Steven Scott, Baltimore, in honor of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the National Museum of Women in the Arts

Heavyweight

The intrepid artists shown in this gallery confound expectations that women work on a more delicate scale than their male counterparts. Sculptural practices such as smelting, welding, and chiseling were historically associated with men, due to the mistaken assumption that women were incapable of manipulating heavy materials. The sculptors here defy this gendered stereotype, casting bronze, crushing aluminum, and wrangling found materials such as rubber and steel.

In two dimensions women are equally bold. Some use unexpected, even hazardous materials like bomb fuses. Others probe institutional power by exploring architectural spaces. Investigating themes of the environment, animals, abstraction, and more, these artists are not afraid to take up space and pull their weight.

Big Horn, 2006

Deborah Butterfield (b. 1949, San Diego)

Cast bronze; Gift of Jacqueline Badger Mars in honor of Wilhelmina Cole Holladay

Butterfield has created her iconic sculptures of horses for more than forty years. A skilled equestrian, she centers her practice on works that, while semi-abstract, demonstrate her knowledge of equine anatomy. More than seven feet tall and nine feet long, Big Horn is named after an area in Bozeman, Montana, close to where Butterfield lives part-time, and where she sourced the materials to create the sculpture. Her creation of Big Horn involved a characteristically labor-intensive process: casting bronze from wooden branches, then assembling and welding them into the structure of the horse, evoking movement, shape, and color.

Orange, 1981

Joan Mitchell (b. 1925, Chicago; d. 1992, Paris)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay; Conservation funds generously provided in honor of Ed Williams by his family

Eridanus, 1984

Lynda Benglis (b. 1941, Lake Charles, Louisiana)

Bronze, zinc, copper, aluminum, and wire; Gift of AT&T Inc.

In Benglis’s hands, heavy becomes light and hard becomes soft. Eridanus, titled after a constellation that alludes to a river in Greek mythology, is part of a series of “knot” sculptures Benglis began in the 1970s. The earliest works in this series were made of plaster-coated chicken wire and covered with paint and glitter. By the 1980s, Benglis embraced a sleeker aesthetic, plating corrugated steel or aluminum wire infrastructures with layers of nickel, zinc, copper, and chrome. These sculptures offer the masterful illusion that metal has been effortlessly pleated, rolled, twisted, or tied as though made of fabric.

Spider III, 1995

Louise Bourgeois (b. 1911, Paris; d. 2010, New York City)

Bronze; Gift of Wilhelmina Cole Holladay

Pasadena Lifesavers Red #5, 1970

Judy Chicago (b. 1939, Chicago)

Sprayed acrylic lacquer on acrylic; Gift of Elyse and Stanley Grinstein

Pasadena Lifesavers Red #4, 1969-70

Judy Chicago (b. 1939, Chicago)

Sprayed acrylic lacquer on acrylic; Gift of MaryRoss Taylor in memory of Carlota S. Smith

Prior to creating consciously feminist art, Chicago contributed to the “look” art movement in Southern California, which paralleled the popular practice of customizing cars and surfboards. Her early techniques—such as the clean shapes, meticulously applied finishes, and luminous, gradated hues visible in this painting—laid the aesthetic foundations for her later work. The series marks Chicago’s initial development of imagery that signifies the essence of the female body but allows for multiple interpretations.

Maelstrom, 2011

Beverly Penn (b. 1955, Baltimore)

Bronze; Museum purchase: Funds provided by the Geiger Family Foundation

Penn casts her bronze flora directly from the plants that she seeks to memorialize. Although the organic matter is lost during this process, the resulting metal forms endure. The rapidly changing climate threatens plant life on our planet, underscoring a need to record and memorialize its diversity. Bronze gives literal weight to the long-term, malign effects of human behavior on our environment. Penn’s work also speaks to the persistence and resilience of nature; although an individual plant may flower and fade, the collective survives as long as conditions remain favorable.

Breakwater, 1990

Dorothy Dehner (b. 1901, Cleveland; d. 1994, New York City)

Steel and paint; Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Gift of the artist)

Kennedy Center (Capital), 2001

Sarah Morris (b. 1967, Sevenoaks, England)

Gloss household paint on canvas; Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

Morris’s angular, abstract paintings investigate architecture and the psychology of urban environments. After visiting Washington, D.C., during the final days of the Clinton administration, Morris created a video work (Capital, 2000) and several paintings that depict iconic structures or power centers, including the Kennedy Center, Dulles International Airport, and the State Department. These complex and layered city portraits trace urban, social, and bureaucratic topologies.

Sunset Over Sea of Bliss, 2001

L. C. Armstrong (b. 1954, Humboldt, Tennessee)

Acrylic, bomb fuse, and resin on linen on wood panel; Gift of Tara Rudman

Blue Shift, 1996

L. C. Armstrong (b. 1954, Humboldt, Tennessee)

Acrylic and bomb fuse under synthetic resin on birch plywood; Gift of Tony and Trisja Podesta Collection

Trained in color theory and illustration, Armstrong creates her colorful compositions with acrylic paint, burn marks, and layers of shiny resin. After moving to New York in the 1980s, she struggled to find her place in abstraction, noting that forms such as stripes and right angles were already associated with other artists. Armstrong came across a coil of bomb fuse and decided to make her mark through burning. “The edgy barbed line left by the smoke residue proved potent on the canvas,” she says, and “a resin finish appealed to my background in Southern California’s car-fetish finish culture.”

Objectified

Still-life painting has long been associated with women artists; this connection grew from attitudes surrounding the supposed appropriateness of the subject matter, limited access to the academic training necessary to master the human form, and the mistaken belief that intellectual rigor was unnecessary—and unobtainable—for its practitioners. In reality, women have shaped the genre since its inception to create skillful and innovative images of food, flowers, vases, and books. These artists have pushed the genre beyond its once narrowly defined scope.

A Gentleman’s Table, after 1890

Claude Raguet Hirst (b. 1855, Cincinnati, Ohio; d. 1942, New York City)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Commissioned by a Chicago men’s club, this still life presents objects that might be found in such a place. However, Hirst’s work may also cast subtle judgment on the drinking and gambling that were common activities in these clubs; the glass at the lower left, containing a slice of lemon and sugar cubes, would have been used to consume absinthe, a potent alcoholic beverage that the artist believed was responsible for her uncle’s death.

Rolls Royce Lady, 1981 (printed 1984)

Audrey Flack (b. 1931, New York City; d. 2024, Southampton, New York)

Cibachrome print; Gift of Diane Singer

Overcrowded and highly detailed, this photograph contains stereotypically feminine luxury items, such as jewelry, perfume, and flowers, alongside a large Rolls Royce hood ornament. This work may appear to reflect an aspiration for opulence, but it is Flack’s interpretation of a vanitas still-life, a genre developed in the seventeenth century that paired the pleasures of the physical world with reminders of life’s brevity and the passage of time. Here, Flack expresses that concept through a watch, an empty wine glass, and a halved lemon, which will ultimately decay.

Doubleweave Basket, 2004

Francine Alex (b. 1950, unknown; d. 2014, Conehatta, Mississippi)

Swamp cane with aniline dyes; Gift of the Mississippi State Committee of NMWA

Leia, 2013

Jiha Moon (b. 1973, Daegu, South Korea)

Ceramic with glaze; Gift of the Georgia Committee of NMWA

Vase, ca. 1929-31

Daisy Makeig-Jones (b. 1881, Wath-upon-Dearn, England; d. 1945, Doncaster, England)

Bone china with underglaze, luster, and gilding; Produced by Wedgwood; Gift of Arthur M. Eckstein and Jeannie Rutenburg

Regency Teapot, 1816

Alice Burrows (Active 1801-ca. 1819, London)

Silver; Silver collection assembled by Nancy Valentine, purchased with funds donated by Mr. and Mrs. Oliver R. Grace and family

Breast Jar, 1990

Kiki Smith (b. 1954, Nuremburg, Germany)

Blown glass; Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Museum purchase: Funds provided by Deane and Paul Shatz)

LDS-MHB-WVBR-0118CE-12, 2018

Jami Porter Lara (b. 1969, Spokane, Washington)

Blackware; Museum purchase: Members’ Acquisition Fund

Jar with Feather Design, ca. 1958

Maria Martinez (b. 1887, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico; d. 1980, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico)

Blackware; Gift in honor of Joan M. Morris by her husband, Hugh

Seed Jar, 1982

Marie Zieu Chino (b. 1907, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico; d. 1982, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico)

Ceramic; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Still Life with a Basket of Plums, Peaches, Cherries, and Redcurrants, Together with Fraises-de-Bois in a Porcelain Bowl, Figs, and Mulberries on a Wooden Ledge, ca. 1630

Louise Moillon (b. 1610, Paris; d. 1696, Paris)

Oil on panel; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Datura, ca. 1930

Imogen Cunningham (b. 1883, Portland, Oregon; d. 1976, San Francisco)

Gelatin silver print; Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Gift of Betsy Karel)

This image exemplifies the crisp, dramatic style of photography for which Cunningham is best known. As a member of Group f/64—photographers who promoted sharp, precisely exposed images—Cunningham rejected the soft or blurred style of Pictorialism, which had been dominant since the nineteenth century. In her images of flowers, Cunningham’s interest in form is evident in the contrast of the plant’s edges against the dark background. Her close observation of her subjects and exacting detail place Cunningham in the tradition of botanical illustration, to which many women contributed.

The Cage, 1885

Berthe Morisot (b. 1841, Bourges, France; d. 1895, Paris)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Untitled (Peonies), 2001

Naomi Fisher (b. 1976, Miami)

Cibachrome print; Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

Fisher’s humorous visualization of the historical association of women and nature reflects the absurdity of the premise. Dating back to the ancient Greeks, the binary that linked women with nature and men with intellect still lies beneath the surface of many gendered stereotypes.

Land Marks

Disparate cultures have linked women to the land through gendered associations with nature, eroticism, and fertility. Paradoxically, civilizations distant in time and place also deplored women’s direct engagement with the “masculine” realm of the great outdoors. Nonetheless, many women defied social constraints to explore the environment and interpret it through their art. Rendered in varied styles and mediums, terrestrial scenes embody humanity’s complex interactions with the natural world, whether portrayed as settings for human intervention, symbols of personal or national identity, or visualizations of an artist’s memories and emotions. As such, landscape art may pique curiosity, evoke subjective responses, and broach long-evaded issues related to power, ownership, and agency.

Hudson River Landscape, 1852

Abigail Tyler Oakes (b. 1823, Charlestown, Massachusetts; d. ca. 1898, unknown)

Oil on canvas; Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Gift of Jeffrey Loria in memory of Ruth and Walter Loria)

By the mid-nineteenth century, landscape imagery in the United States embodied both expansionist ideology and national identity. Whereas images of the western frontier increasingly upheld contemporary rhetoric about the nation’s predestined right to territorial dominance, Oakes’s painting of idyllic scenery almost devoid of human presence appealed to Americans’ romantic nostalgia for a pre-industrial past. Oakes, who resided mostly in New York City, spent several years in San Francisco, and is considered one of the first professional women artists in California.

View of the Connecticut River Valley, 1854

Abigail Tyler Oakes (b. 1823, Charlestown, Massachusetts; d. ca. 1898, unknown)

Oil on canvas; Museum purchase: Funds provided by Dr. Robert A. Beckman and Family in honor of Marion Forman Beckman

Highland Raid, 1860

Rosa Bonheur (b. 1822, Bordeaux, France; d. 1899, Thomery, France)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Group of Four (Cornwall), 1965

Barbara Hepworth (b. 1903, Wakefield, England; d. 1975, St. Ives, England)

Slate; Gift of Wilhelmina Cole Holladay

Neolithic standing stones in Cornwall, England, provided abundant inspiration for Hepworth. The loosely identical vertical forms in Group of Four (Cornwall) echo those mysterious Mehnirs, while also reflecting the artist’s abiding belief: “There is no landscape without the human figure.” Here, the four slate slices appear animated, leaning or turning slightly as if to engage with one another. Through such works, Hepworth sought to convey not the literal appearance of the landscape, but her experience as part of it.

Red Shack in Yellow Field, 2004

Beverly Buchanan (b. 1940, Fuquay-Varina, North Carolina; d. 2015, Ann Arbor, Michigan)

Oil pastel on paper; Gift of Anna Stapleton Henson

Staffelsee in Autumn, 1923

Gabriele Münter (b. 1877, Berlin; 1962, Murnau, Germany)

Oil on board; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Arreau, Hautes-Pyrénées, 1949

Loïs Mailou Jones (b. 1905, Boston; d. 1998, Washington, D.C.)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Gladys P. Payne

Jones first traveled to Paris in 1937, while on sabbatical from Howard University, and summered in France annually from 1946 to 1953. Her portrayal of the picturesque village of Arreau in southwestern France evokes landscape paintings by Paul Cézanne, a stylistic influence she acknowledged. Loose brushwork defines the structures of buildings and topography; the intense contrast of oranges and greens suffuses the peaceful scene with vibrancy. This work received an award from Washington, D.C.’s Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1949.

Rainy Night, Downtown, 1967

Georgia Mills Jessup (b. 1926, Washington, D.C.; d. 2016, Columbia, Maryland)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Savanna M. Clark

Through complex patterning, vivid colors, and stark lighting contrasts, Jessup captured the visual energy of a bustling downtown. The scene includes shops and a theater previously located just one block from the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Jessup, a self-described “melting pot” for her mixed African American and Native American heritage, had deep roots in Washington, D.C., and worked in the city as an artist, art educator, and arts advocate.

Slumber Party, 2000

Justine Kurland (b. 1969, Warsaw, New York)

Chromogenic color print; Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

For more than two decades, Kurland nurtured her penchant for a nomadic lifestyle by creating photographic series during extended road trips through the American Northwest and South. Working with volunteer models she met during her travels, Kurland staged scenarios that often reference nineteenth-century romantic landscapes, painting, and photography. In the series “Girl Pictures” (1997-2002), which includes Slumber Party, the artist sought to portray a world “where solidarity between girls offered intimacy and protection.”

Tableau vivant I, 2001 (printed 2005)

Mónica Castillo (b. 1961, Mexico City)

Digital print on paper; Gift of the artist

The River, 2012

Anne Appleby (b. 1954, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania)

Color aquatint with burnishing on paper; Promised gift of Steven Scott, Baltimore, in honor of the artist

Though often termed “reductive,” Appleby’s prints and paintings reveal their complexity through time and attention, not unlike the landscapes they represent. Appleby arrives at her palette and composition by distilling decades of personal experience observing the cycles of nature near her Montana home. The two nuanced color fields comprising The River evoke the tree-lined waterway on her property. Appleby contrived these precise hues by printing four plates per panel, each delivering a slight variation of meticulously mixed pigment.

The Springs, 1964

Lee Krasner (b. 1908, Brooklyn, New York; d. 1984, New York City)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Yara, Cairo, Egypt, from the series “SHE,” 2019

Rania Matar (b. 1964, Beirut)

Archival pigment print; Museum purchase: Funds provided by Sunny Scully Alsup and Elva Ferrari-Graham

In the early 2000s, Matar embraced photography to grapple with the aftermath of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-90) and respond to divisive, post-September 11 rhetoric about the Middle East. Her series “SHE,” photographed in the Middle East and United States, captures commonalities of young womanhood across religious, geographical, and cultural borders. The images portray women in their early twenties in dramatic settings, removed from the familiarity of childhood homes. Matar recalls, “It was as [though Yara] became one with the tree on her own.”

Indian, Indio, Indigenous, 1992

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, b. 1940, St. Ignatius, Montana)

Oil and collage on canvas; Museum purchase: Members’ Acquisition Fund

Figure (Merryn), 1962

Barbara Hepworth (b. 1903, Wakefield, England; d. 1975, St. Ives, England)

Alabaster; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

No Shrinking Violet

A rich, sensual, and versatile hue, the color purple has traditionally been used in art to depict spirituality, nobility, amition, and power. The children’s author Crockett Johnson once said that “purple is the color of adventure.” And the writer Alice Walker, renowned for works including The Color Purple (1982), used the analogy, “Womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender,” to express the need for feminism to encompass the perspectives of Black women, thereby building a feminism that is “Stronger in color.”

Purple is an avenue of innovation for the historical and contemporary artists in this gallery. Rather than shy away from a male-dominated art world, they observe, experiment, originate, and make critical social commentary through the bold and inspired use of purple in all its shades.

Bennington Birches, 1994

Patricia Tobacco Forrester (b. 1940, Northampton, Massachusetts; d. 2011, Washington, D.C.)

Watercolor on paper (diptych) Bequest of the artist

Acclaimed for large-scale watercolors painted outdoors rather than in the studio, Forrester rendered scenery throughout the U.S., Europe, and the Caribbean, as well as Central and South America. She delighted in her medium: “The accidental nature of watercolor—the fact that paint moves across the paper—is my partner in the work.” Though she worked directly from life, Forrester did not rigorously imitate nature. She intensified colors, compressed perspective, and combined landscape elements from different locales within single compositions.

Purple Atmosphere, 2019

Judy Chicago (b. 1939, Chicago)

ChromaLuxe print on aluminum; Museum purchase: Funds provided by MaryRoss Taylor

Purple has a long association with the American women’s movement and efforts to achieve gender equality. In the early 1900s, it became an official color of the National Women’s Party and the suffragists campaigning for women’s right to vote. It is likewise linked to contemporary feminism and its many achievements. In her famed Atmospheres, performance works staged from 1968 to 1974, Chicago sought to “feminize” the landscape with billowing smoke in soft, pastel tones like the purple seen here. This recent work uses an image of an Atmosphere that Chicago created in 1969.

Winter with Cynical Fish, 2014

Hung Liu (b. 1948, Changchun, China; d. 2021, Oakland, California)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Fred M. & Nancy Livingston Levin, The Shenson Foundation in memory of Ben & A. Jess Shenson

Liu created these two paintings as part of an untitled series from 2012 to 2014, each representing one of the four seasons. She adapts the sullen fish imagery from the paintings of the eminent Chinese artist and calligrapher Bada Shanren (born Zhu Da, ca. 1625-1705), whose satirical pictures of birds and fish reflected moods such as sadness, anger, or cynicism. By pairing Bada’s symbols of high art and culture with poor, working-class women, Liu places the latter among those in the highest social strata.

Jeune femme en mauve (Young Woman in Mauve), 1880

Berthe Morisot (b. 1841, Bourges, France; d. 1895, Paris)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long

One of the three “grandes dames” of Impressionism, alongside Mary Cassatt and Marie Bracquemond, Morisot was an essential member of this radical art movement. Rapid, spontaneous notes of lilac and violet brushstrokes in the elegant sitter’s dress and radiating around her figure illustrate Morisot’s Impressionist handling of the vogue for the color mauve. Accidentally discovered in 1856 by a young English chemist, mauve dye became the first mass-produced synthetic color in the nineteenth century, sparking a mauve mania in Western fashion and design.

Girl on a Small Wall, 1930

Suzanne Valadon (b. 1865, Bessines-sur-Gartempe, France; d. 1938, Paris)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

La Petite Modèle, ca. 1915-20

Gwen John (b. 1876, Haverfordwest, Wales; d. 1939, Dieppe, France)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Through the Flower 2, 1973

Judy Chicago (b. 1939, Chicago)

Sprayed acrylic on canvas; On loan from Diane Gelon

T.B. Harlem, 1940

Alice Neel (b. 1900, Merion Square, Pennsylvania; d. 1984, New York City)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Carlos Negrón, the brother of Neel’s lover José Santiago, is seen here bandaged from his thoracoplasty, a procedure that collapsed and “rested” tuberculosis-infected lungs by removing ribs. Negrón had moved from his native Puerto Rico to New York’s Spanish Harlem neighborhood, where tuberculosis spread easily in the crowded urban environment. Neel is known for her bold color choices; here, her use of an otherwise neutral palette of browns, whites, and blacks makes the contrasting purple even more striking. The strong diagonal line—a classic compositional device—keeps the viewer’s eyes moving and furthers the work’s psychological intensity.

Gwendolyn Purdon Clark, ca. 1908-10

Eulabee Dix (b. 1878, Greenville, Illinois; d. 1961, Waterbury, Connecticut)

Watercolor on ivory; Gift of Mrs. Philip Dix Becker and family

Portrait of a Woman (after Antoine Vestier), ca. 1904

Eulabee Dix (b. 1878, Greenville, Illinois; d. 1961, Waterbury, Connecticut)

Watercolor on ivory; Gift of Mrs. Philip Dix Becker and familyEthel Barrymore, ca. 1905

Eulabee Dix (b. 1878, Greenville, Illinois; d. 1961, Waterbury, Connecticut)

Watercolor on ivory in ivory box; Gift of Mrs. Philip Dix Becker and family

The Coral Earrings, ca. 1910

Eulabee Dix (b. 1878, Greenville, Illinois; d. 1961, Waterbury, Connecticut)

Watercolor on ivory in wood frame; Gift of Joan B. Gaines

Me, ca. 1899

Eulabee Dix (b. 1878, Greenville, Illinois; d. 1961, Waterbury, Connecticut)

Watercolor on ivory; Gift of Mrs. Philip Dix Becker and family

Seeing Red

Red, more than other hues, commands attention. Although specific responses to it reflect personal experience and cultural influences, across time and space red consistently provokes emotional extremes and antithetical associations. Shades of crimson, cherry, ruby, and rose, among others, can seduce or warn, allude to ardent love or impassioned anger, and signify both danger and good fortune. It evokes our life’s blood as well as fire, a source of vital warmth but also fearsome energy. Some artists use red to replicate enticing details of flora; others employ it to illuminate their emotional responses and elicit ours. The color serves symbolic purposes, yet also formal ones: organizing a composition or creating visual rhythm. Artists wield red deliberately, exploiting its powerful influence on the ways we respond to and interpret their work.

Vase of Flowers I, 1999 (printed in 2011)

Amy Lamb (b. 1944, Burmingham, Michigan)

Pigment print on paper; Gift of the artis and Steven Scott Gallery, Baltimore, in honor of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the National Museum of Women in the Arts

Selected plates from Dissertation in Insect Generations and Metamorphosis in Surinam, 2nd edition, 1719

Plate 55: Pepper Plant with Carolina Sphinx Moth

Plate 60: Branch of Cardinal’s Guard with Giant Owl Butterfly

Maria Sibylla Merian (b. 1647, Frankfurt, Germany; d. 1717, Amsterdam)

Hand-colored engraving on paper; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Unlike most seventeenth-century naturalists, Merian studied living creatures in their native habitats rather than preserved specimens found in curiosity cabinets. Compelled to travel to satisfy her scientific curiosity, she spent two years in the Dutch colony of Suriname in South America. Merian’s meticulous watercolor studies and field notes from that trip served as source material for her influential book on insect metamorphosis, from which these hand-colored engravings derive. Both scientifically informative and aesthetically arresting, her innovative compositions present an insect’s life cycle in a continuous narrative arrayed on and around its primary food source. Portraying both the beauty and the violence of the rainforest ecosystem, Merian’s vivid illustrations introduced many American plants and insects to a European audience for the first time.

Marriage Portrait of a Bolognese Noblewoman (Livia de’ Medici Bandini?), ca. 1589

Lavinia Fontana (b. 1552, Bologna, Italy; d. 1614, Rome)

Oil on canvas; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay; Frame conservation funds generously provided by the Texas State Committee of the National Museum of Women in the Arts

A leading portraitist in sixteenth-century Bologna, Fontana painted many lavishly attired young women. Although this sitter’s identity remains provisional, the sumptuous garnet-colored gown and opulent accessories signal her circumstances. The city’s elite brides typically wore red, so this portrait likely commemorates marriage. Her jeweled cross, affectionate pet, and averted gaze verify then-requisite womanly virtues: piety, loyalty, and modesty. The richly adorned pelt of a marten (a slender mink-like creature) in the bride’s left hand was a fertility talisman, a conspicuous reminder of a married woman’s primary obligation.

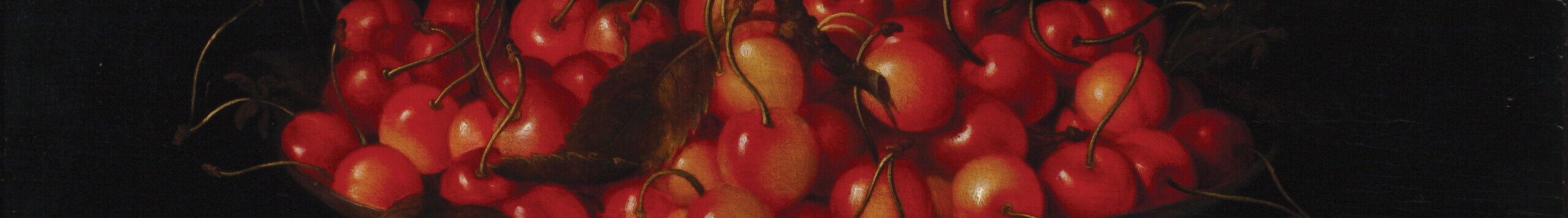

Cherries in a Silver Compote with Crabapples on a Stone Ledge and a Fritillary Butterfly, ca. 1610

Fede Galizia (b. 1578, Milan; d. ca. 1630, Milan)

Oil on panel; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Boundary Lines, 2009

Clare Rojas (b. 1976, Columbus, Ohio)

Color aquatint, spitbite aquatint, and sugar-tint etching on paper; Gift of Steven Scott, Baltimore, in memory of his graduate professor Dr. Elizabeth Johns

In the early 2000s, Rojas took inspiration from street art and folk art, blending flat planes of color with vivid patterns that recall quilting and paper-cutting. Boundary Lines features a demurely styled figure hesitating before a field of poppies, their vivid hue acting as both sensory enticement and danger signal. Rojas notes, “Poisonous people, poisonous imagery, poisonous poison. You’re just trying to protect yourself from it . . . no matter how alluring it may seem.”

Scorch Song, 2022

Alison Saar (b. 1956, Los Angeles)

Wood, found mini skillets, nails, and tar; Museum purchase: Funds provided by Steven Scott, Baltimore, in honor of the artist and the thirty-fifth anniversary of the National Museum of Women in the Arts

Pregnant Nana, 1995

Niki de Saint Phalle (b. 1930, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France; d. 2002, La Jolla, California)

Painted marble; Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Gift of Jeffrey H. Loria)

Magnetic Fields, 1990

Mildred Thompson (b. 1936, Jacksonville, Florida; d. 2003, Atlanta)

Oil on canvas; Gift of the Georgia Committee of NMWA in honor of the thirtieth anniversary of the Georgia Committee and the National Museum of Women in the Arts

In her “Magnetic Fields” series, Thompson explored scientific phenomena and forces invisible to the naked eye. This composition’s frenetic energy owes much to her command of color theory. Slashes of bold crimson spiral and arc against a luminous yellow field, creating visual vibrations. Strokes of blue, orange, and pink further intensify the optical dynamism. Thompson’s paintings were long overlooked by critics, because her interest in science and abstraction confounded their expectations for works by African American artists.

Acrylic No. 3, 1988, 1988

Fanny Sanín (b. 1938, Bogotá, Colombia)

Acrylic on canvas Gift of the artist

Orion, 1973

Alma Woodsey Thomas (b. 1891, Columbus, Georgia; d. 1978, Washington, D.C.)

Acrylic on canvas; Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

In her late seventies, Thomas developed a signature style, characterized by brightly colored, lozenge-shaped brushstrokes arranged in stripes and puzzle-like patterns. Though abstract, her paintings reflect direct experience of nature. Captivated by NASA’s Apollo missions in the late 1960s, Thomas also looked heavenward. Orion alludes to the constellation without portraying it literally. Her mosaic-like brushwork suggests flickering starlight, while the palette of varied reds signifies the heat and energy required to break Earth’s gravity.