Introduction

Between 1600 and 1750, women played a vital role in the artistic life of the Low Countries (present-day Belgium and the Netherlands)—but their stories have long gone untold.

In an era that produced some of the most renowned figures in art history, such as Rembrandt van Rijn, Peter Paul Rubens, and Johannes Vermeer, countless women artists also lived and worked. This exhibition presents the work of many of those women, demonstrating the breadth of their contributions to the visual culture of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Women painters, printmakers, sculptors, and even paper cutters were widely recognized and praised for their achievements during their lifetimes. These women artists, mainly from the middle and upper classes, had access to professional training through family members or teachers. Also featured are textiles such as lace and embroidery, generally produced by women from the lower classes whose names were not recorded. While their individual stories are no longer known, their intricate and expensive handiwork is visible in countless portraits from the period, as sitters sought to demonstrate their wealth.

Presented within unifying themes, this exhibition explores the presence of women artists across class, material, and genre; their training and contributions to the local and global artistic economy; and how and why their legacies have been obscured. It offers a survey of the many ways in which women helped to shape and define the visual culture of one of the most dynamic periods in history.

Judith Leyster

b. 1609, Haarlem, the Netherlands; d. 1660, Heemstede, the Netherlands

Self-Portrait, ca. 1630

Oil on canvas; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, inv. 1949.6.1

Leyster clearly identifies herself as a painter in this self-portrait she holds her palette and brushes while gesturing to her work in progress on the canvas. The artist depicts herself dressed fashionably, in high-quality clothes, to convey her social status and professionalism. Leyster was admitted into the painters’ guild in the city of Haarlem around the same time she created this self-portrait. Membership enabled her to take on clients and run a workshop of her own, which also included training apprentices.

Maria van Oosterwijck

b. 1630, Nootdorp, the Netherlands; d. 1693, Uitdam, the Netherlands

Vanitas Still Life, 1668

Oil on canvas; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, inv. 5714

Van Oosterwijck was a renowned painter in Amsterdam, and her patrons included Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, for whom she painted this work. Although she specialized in floral still lifes, her vase of flowers is not the center of attention here. Rather, it is one of many elements in this “vanitas” still life, so-called because of symbols alluding to the brevity of life, such as a human skull and an hourglass. In the reflection of the glass bottle labeled “Aqua Vitae” (“Water of Life”), Van Oosterwijck painted her only known self-portrait.

Presence

Portraits of women artists, their signatures, and existing works in a wide range of mediums and genres attest to their presence during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

Through self-portraits and prominent signatures, women identified themselves as artists. Whether they depicted themselves with the tools of their trade or conspicuously and proudly placed their signatures on their work, women were not hesitant to declare their roles as creators. Portraits of them by others indicate the respect and renown they enjoyed in society. Some were immortalized in paint by peers or family members, and others enshrined within the pages of published biographies, which ostensibly ensured their legacies far and wide.

Women created art in a variety of materials—paintings, lace, sculptures, paper cuttings, and more—and addressed diverse subject matter. In the next gallery, and throughout the exhibition, works on view exemplify this versatility.

Maria Schalcken

b. ca. 1645/50, Dordrecht, the Netherlands; d. ca. 1700, likely Dordrecht, the Netherlands

Self-Portrait in Her Studio, ca. 1680

Oil on panel; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo, in support of The Center for Netherlandish Art, inv. 2019.2094

Schalcken, like her compatriot Judith Leyster earlier in the century, leans assuredly over the back of her chair and gestures toward her easel, which holds a completed landscape painting. While no such painting by Schalcken is known today, its appearance demonstrates that she was proficient in this genre as well as portraiture. She was trained by her brother, Godefridus Schalcken (1643–1706). As their painting styles are very similar, Schalcken’s art, including this work, has been mistakenly attributed to her brother in the past.

Maria Faydherbe

b. 1587, Mechelen, Belgium; d. after 1633, location unidentified

Virgin and Child, ca. 1632

Palm wood; M Leuven, inv. C/706

Carved into the wood at the base of this sculpture are the Latin words “MARIA FAYDHERBE ME FECIT.” Translated as “Maria Faydherbe made me,” this signature is remarkable not just for its unapologetic declaration of authorship, but also because it was rare for any sculptor in the city of Mechelen at the time to sign their work. Faydherbe was not born into an artistic family, but she and two of her brothers became sculptors, and together they formed a family business.

Judith Leyster

b. 1609, Haarlem, the Netherlands; d. 1660, Heemstede, the Netherlands

Self-Portrait, ca. 1640

Oil on panel; Private collection

Presented here for the first time alongside her earlier and better-known self-portrait, this image of Leyster is likely the one listed in the inventory of her husband, artist Jan Miense Molenaer (1609/10-68), after his death. As it was still in his possession, this self-portrait was probably a more private, personal work, in contrast to the larger and more exuberant image of ca. 1630. In this later painting, only rediscovered in 2016, Leyster still presents herself as an artist at midlife.

Wenceslas Hollar

b. 1607, Prague; d. 1677, London

Portrait of Anna Francisca de Bruyns, 1648

Engraving on paper; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Gift from Frank Raysor, inv. FR.4135.1

Compared with many other women artists of the period, De Bruyns’s life was well documented, thanks to the writings of her son, Jacques Ignace Bullart. He was likely also the person who ensured that this print was created, copied from a self-portrait (now lost) that his mother painted in 1629, at twenty-four years old. De Bruyns also painted many historical and religious scenes, including a large altarpiece still in place at the church of Notre Dame de Bon Vouloir in Havré, Belgium.

Geertruydt Roghman

b. 1625, Amsterdam; d. 1651/57, Amsterdam

A Young Woman Ruffling, from the series

“Five Feminine Occupations,” ca. 1640–57

Engraving on paper; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1956, inv. 56.550.3

Although we can no longer identify many of the countless women who produced textiles during this period, artists commonly depicted them. Sewing was considered industrious and virtuous for women of all social classes, and images of women engaged in the task often had moralizing overtones: here, the skull symbolizes the brevity of life. This image of a woman preparing a length of fabric for “ruffling,” or gathering folds of fabric for decorative effect, is one of five prints by Roghman from a series of women carrying out domestic duties.

Princess Louise Hollandine of the Palatinate

b. 1622, The Hague, the Netherlands; d. 1709, Val-d’Oise, France

Self-Portrait, ca. 1650–55

after Gerard van Honthorst

Oil on canvas ; Private collection, through the Hoogsteder Museum Foundation, The Hague

Louise Hollandine, Princess of the Palatinate, was the daughter of Elizabeth Stuart and Frederick V of the Palatinate and lived with them in exile in the Dutch Republic. Born and raised in The Hague, she received instruction in painting from the established artist Gerard van Honthorst (1592–1656). This portrait of her is a copy that the princess made of one painted by Honthorst, now in the collection of the National Trust, U.K. Copying the work of their teachers was a common training technique for painters at the time.

Unidentified artist (GM)

Northern Netherlands

Embroidered darning sampler, 1761

Silk on linen ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, From the collection of Mrs. Lathrop Colgate Harper, bequest of Mabel Herbert Harper, 1957, inv. 57.122.144

The maker of this darning sampler proudly embroidered her initials, “GM,” along with the date she presumably completed it. It demonstrates her skill in several different stitches, including a small circle of needlepoint lace at the upper left. The border, embellished with an embroidered vine of flowers, is typical of the decoration found on high-quality clothing of the period. This type of delicate textile only rarely survives; its maker and her family likely took great pride and care in its preservation.

Gesina ter Borch

b. 1631, Deventer, the Netherlands; d. 1690, Zwolle, the Netherlands

Materi-Boeck, 1648

Pen and brush on paper; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Purchased with the support of the Rembrandt Association, inv. BI-1890-1950-10

When she was just fifteen, Ter Borch inscribed the title page of this album, which she then filled with calligraphy and sketches. Using her childhood nickname, “Geesken,” she identifies this book as hers while also displaying her calligraphic skills. Albums such as these, of which three by Ter Borch survive, were used by artists to preserve their work and often include inscriptions by friends and admirers.

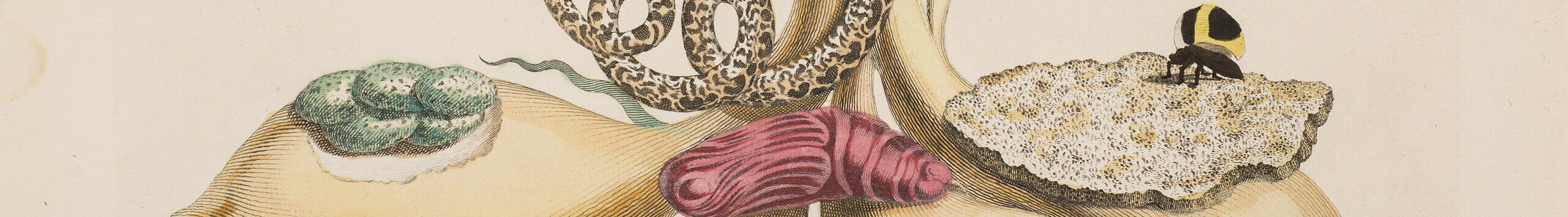

Maria Sibylla Merian

b. 1647, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; d. 1717, Amsterdam

Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandelung und sonderbare Blumennahrung (The Wondrous Transformation of Caterpillars and Their Strange Diet of Flowers), vol. 2, 1683

Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, Virginia

In the frontispiece for the second volume of her book on the life cycle of caterpillars, Merian created a decorative floral wreath upon which insects alight, crawl, and hover. Her signature at the bottom (using her married surname) and the Latin word “sculpsit” indicate that she also made the engraving. The publication features one hundred illustrations by Merian that faithfully reproduce the life stages and host plants of a variety of moths, butterflies, and their larvae, which she observed from life.

Arnold Boonen

b. 1669, Dordrecht, the Netherlands; d. 1729, Amsterdam

Portrait of Catharina Backer, 1713

Oil on canvas; Amsterdam Museum, Long-term loan from Foundation Backer, inv. AM SB 2530

Backer was born into one of the wealthiest families in Amsterdam and grew up surrounded by her parents’ art collection. Along with being educated in multiple subjects and languages, she received artistic training. An album on view in this exhibition contains many of her drawings, including nudes, various anatomical studies, and images of ancient sculptures. In this portrait, Backer is portrayed as a painter of floral still lifes, a genre which she seems to have preferred.

Maria Theresia van Thielen

b. 1640, Antwerp; d. 1706, Antwerp

Still Life with Parrot, 1661

Oil on canvas; Milwaukee Art Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John Schroeder in memory of their parents, inv. M1967.41

Van Thielen, along with her sisters, Anna and Francisca, was praised during her lifetime by the writer Cornelis de Bie in 1662 as “artistically rich and virtuous.” All three sisters were trained by their father, although no works by Anna or Francisca are known today. Only a few works by Van Thielen have been identified, and this example demonstrates her considerable skill. She signed and dated it on the stone ledge below the parrot’s perch, an indication that Van Thielen found success and pride in her art.

Maria Sibylla Merian

b. 1647, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; d. 1717, Amsterdam

Erucarum Ortus (The Birth of Caterpillars), 1718

Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, Virginia

Merian used her artistic talents to document the natural world. The portrait of her visible here, engraved after one by her son-in-law, Georg Gsell (1673–1740), appears in the posthumous Latin publication of her work on the metamorphosis of caterpillars, which she had published in German and Dutch during her lifetime. Although she died shortly before the Latin edition was published, Merian was highly involved in the process, knowing that publishing her work in the lingua franca of the scientific community would ensure a wider audience.

Arnold Houbraken

b. 1660, Dordrecht, the Netherlands; d. 1719, Amsterdam

Left to right:

Portraits of Maria Sibylla Merian and David van der Plaas

Portraits of Anna Maria van Schurman, Rembrandt van Rijn, and Jacob Adriaensz Backer

De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (The Great Theatre of the Netherlandish Painters and Paintresses), 1753

National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, D.C., inv. ND652.H86

Houbraken wrote and published three volumes of biographies of Dutch and Flemish artists of the era.

His inclusion of women is apparent from the title, which uses the feminine form of “painters” in Dutch:

schilderessen. While his inclusion of twenty-four women was significant—more than any other biographer to that point—they represent just a small fraction of the more than five hundred artists he profiled. The portraits of Anna Maria van Schurman and Maria Sibylla Merian, seen here, were included, as was a portrait of Johanna Koerten on view in the “Legacy” section of this exhibition.

Cornelis de Bie

b. 1627, Lier, Belgium; d. ca. 1712–15, Lier, Belgium

Van Thielen sisters in Het Gulden Cabinet vande edele vry schilder-const (The Golden Cabinet of the Noble Liberal Art of Painting), 1662

National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, D.C., inv. N6972. B5

After the Italian artist and writer Giorgio Vasari published a compilation of artist biographies in the sixteenth century, other writers throughout Europe began to do the same, focusing on artists of their regions. De Bie, writing in the Southern Netherlands, used Vasari and other earlier writers as sources, but also made additions that he believed merited inclusion. He gave the Van Thielen sisters their own heading and lauded their skill in the genre of flower painting.

Michiel van Musscher

b. 1645, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; d. 1705, Amsterdam

Allegorical Portrait of an Artist in Her Studio, ca. 1675-85

Oil on canvas; North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, Gift of Armand and Victor Hammer, inv. G.57.10.1

While the identity of this sitter has not been confirmed, Van Musscher is known to have collaborated with still-life painter Rachel Ruysch on a portrait of her now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This woman may also portray Ruysch or another painter such as Maria van Oosterwijck, or she may be an allegorical figure representing the art of still-life painting. Either way, this large and detailed work glorifies the genre of still life and its practitioners.

Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen

b. 1593, London; d. 1661, Utrecht, the Netherlands

Portrait of Anna Maria van Schurman, 1657

Oil on panel; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Gift of Joseph F. McCrindle, inv. 2002.35.1

This grisaille, or monochrome, portrait of Van Schurman was made as a model for the print also on view here. One of the most celebrated individuals of her time, Van Schurman was renowned for her erudition. The objects that surround her allude to her many achievements in painting and drawing, embroidery, music, literature, and more. In the background, Utrecht’s cathedral tower references the city where Van Schurman lived and attended university.

Cornelis van Dalen the Younger

b. 1638, Amsterdam; d. before 1664, location unknown

Portrait of Anna Maria van Schurman, after 1657

after Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen

Engraving on paper; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Gift of the Estate of Leo Steinburg, inv. 2011.139.43

This print was made after the preparatory monochrome painting of Van Schurman. Here, the blank space left by the artist in the painting has been filled in with a laudatory inscription in Latin written by one of the most prominent luminaries in the Dutch Republic, Constantijn Huygens. Van Schurman’s fame, already considerable, would have been significantly enhanced by the circulation of this print.

Anna Maria van Schurman

b. 1607, Cologne, Germany; d. 1678, Wieuwerd, the Netherlands

Left to right:

Self-Portrait, 1640

Engraving on paper; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay, inv. 1986.339.1

Self-Portrait, 1640

Drypoint on paper; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay, inv. 1986.339.2

By the time Van Schurman made these self-portraits at age thirty-three, she was already famous for being the first woman to attend university in the Dutch Republic and for knowing multiple languages, including ancient Greek, Arabic, and Hebrew. Van Schurman was an accomplished artist not only in printmaking, but also in painting, carving, and wax work. Despite her talents, the inscription below these prints modestly asks the viewer to “perfect the work where art has failed.”

Jacob Cats

b. 1577, Brouwershaven, the Netherlands; d. 1660, The Hague, the Netherlands

Alle de wercken, so oude als nieuwe (All Works, Both Old and New), 1655

National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, D.C., inv. PT5630. H8 164

The writer Jacob Cats was a friend to Van Schurman and her family; he included this colored reproduction of one of her self-portraits in the publication of his collected works. Below the image, the inscription written by Cats reads, “Whoever comes to see this beautiful image, / Be assured that you see here a glory for all women. / From that time the world arose to this day / Not one resembles her or could be compared to her.”

Wallerant Vaillant

b. 1623, Lille, France; d. 1677, Amsterdam

Portrait of Maria van Oosterwijck, 1671

Oil on canvas; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, inv. SK-A-1292

Van Oosterwijck, whose Vanitas Still Life is on view nearby, studied with the preeminent floral still-life painter Willem van Aelst (1627–1683). Throughout her lifetime, she received many prominent commissions and was praised in laudatory poems by the Amsterdam literati. Van Oosterwijck’s rich satin jacket and lace-trimmed chemise indicate her social status, while the items in her lap—a book as well as palette and brushes—underscore the different aspects of her education.

Gabriel Metsu

b. 1629, Leiden, the Netherlands; d. 1667, Amsterdam

Portrait of Maria de Grebber, ca. 1660

Oil on panel; Stedelijk Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden, Gift, 2004, inv. S 5417

Metsu offers a candid glimpse of his mother-in-law, Maria de Grebber, at work painting. De Grebber came from a well-known artistic family in Haarlem. This portrait, created when she was in her late fifties, indicates that she was still painting. The writer Arnold Houbraken stated that De Grebber “practiced art with great distinction and [was] also competent in architecture and perspective.” Today, however, only one work is known by her, a portrait of Augustinus de Wolff on view in the “Choices” section of this exhibition.

Nicolaas Juweel

b. ca. 1639, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; d. 1704, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Portrait of a Paper Cutter, possibly Alijda Juweel, in Rotterdam, 1696

Oil on panel; Rotterdam Museum, inv. 67112

Paper-cutting art was one of the most expensive and fashionable types of luxury objects of the period, and its practitioners were widely celebrated. The woman portrayed here, who may be artist Nicolaas Juweel’s daughter, holds aloft a highly detailed and intricate three-dimensional paper cutting, as the man behind her looks on in amazement. Due to the fragility of such works, many have not survived.

Gerrit van Goor

b. 1645, Amsterdam; d. 1695, Amsterdam

Portrait of Cornelia de Rijk, 1689

Oil on canvas; Private collection, Netherlands

Cornelia de Rijk was known for her paintings of fowl such as geese and chickens, as well as exacting drawings of insects, examples of which are on display in this exhibition. This portrait was painted by her first husband around the time of their marriage. De Rijk is shown in her studio, gesturing to the painting on her easel, while the folios in the background may include her preparatory drawings.

Networks

Works by women were essential to the artistic economies of the Low Countries: they found eager consumers and patrons locally, across Europe, and around the globe.

Objects on view here demonstrate that women artists were connected to each other and to their wider artistic communities. They made technical and stylistic innovations, and patrons bought their work through the open market as well as through important commissions.

Women artists were also active in early scientific networks, creating accurate and detailed images of plants and insects, which in turn were often published. In an era before photography, such illustrations and publications were crucial in sharing knowledge of species, particularly those previously unknown to Europeans.

Echoes of the vicious colonial expansion that engendered the influx of wealth into the Low Countries are evident in the subject matter, imagery, and materials of the works on view. Some women also produced work specifically for export to colonies in the Americas. Women artists, like their male counterparts, took advantage of and grappled with their rapidly changing world.

Susanna van Steenwijck-Gaspoel

b. after 1602, London; d. 1664, Amsterdam

View of the Lakenhal, 1642

Oil on canvas; Stedelijk Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden, inv. S 410

The earliest known woman to specialize in architectural painting, Van Steenwijck-Gaspoel here depicted the Leiden cloth merchants’ guild, the Lakenhal. She painted this view without a commission and offered it to the city council several times before they purchased it, for the large sum of 600 guilders. Having likely learned architectural painting from her husband, Hendrik van Steenwijck the Younger (ca. 1580-1649), she continued after his death and, as a biographer noted, “earned so much [from her art] that [her family] could support themselves well and honestly.”

Magdalena van de Passe

b. 1600, Cologne, Germany; d. 1638, Utrecht, the Netherlands

Top, left to right.

Coastal Scene with a Ship at Sea and a Fire in the Background, from the series “Four Landscapes with Scenes from the Story of Elijah,” ca. 1620–30

after Adam Willaerts

Engraving on paper; The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: The Print Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Rocky Landscape, ca. 1620–30

after Paul Bril

Engraving on paper; The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: The Print Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations, Samuel Putnam Avery Collection

Landscape with a Stable, ca. 1620–30

after Paul Bril

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: The Print Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Bottom, left to right.

The Prophet Elijah on a Rock in a Landscape with Mountains and a River, from the series “Four Landscapes with Scenes from the Story of Elijah,” ca. 1620–30

after Roelant Savery

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: The Print Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

The Prophet Elijah on a Beach with Fishers Cutting Up a Whale, from the series “Four Landscapes with Scenes from the Story of Elijah,” ca. 1620–30

after Adam Willaerts

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: The Print Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

The Prophet Elijah Receiving Bread from the Raven in a Landscape with Mountains and a River, from the series “Four Landscapes with Scenes from the Story of Elijah,” ca. 1620–30

after Roelant Savery

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: The Print Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Van de Passe was trained in the family business of printmaking, along with her brothers, by their father, Crispijn van de Passe the Elder (1564–1637). She frequently collaborated with her father, as seen in these prints which carry both of their signatures. Van de Passe specialized in landscapes, reproducing paintings by famous artists of the day, for which there was a large market. She also taught Anna Maria van Schurman the art of engraving.

Johanna Koerten

b. 1650, Amsterdam; d. 1715, Amsterdam

Portrait of Peter the Great, Tsar of Russia, 1697–1715

Paper cutting; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, On loan from the Royal Archaeological Society, inv. KOG-ZG-1-18A-117

One of the visitors Koerten welcomed to view examples of her work was Tsar Peter the Great of Russia, an indication of her international reputation. Koerten created his portrait, as she did with many other illustrious people of the time, including King William III of England, also on view in the exhibition. In this portrait of the Russian Tsar, Koerten skillfully uses shading cuts to render different materials, such as his soft ermine stole and rigid armor.

Attributed to Anna Maria van Schurman

b. 1607, Cologne, Germany; d. 1678, Wieuwerd, the Netherlands

Cut-out artwork with Star of David and AM monogram, ca. 1650

Paper cutting; Museum Martena, Franeker, inv. S0005

This intricate paper cutting was either made by Van Schurman or for her by a friend or admirer. At the center is a Star of David (Hebrew was one of the many languages that Van Schurman studied), while her monogram, “AM,” appears at the bottom. Items such as this were often exchanged as tokens of friendship and admiration.

Elisabeth Seldron

b. 1681/82, Brussels, Belgium; d. 1761, Brussels, Belgium

Festivities After Taking a City, 1741–48

Oil on canvas; STAM, Ghent, inv. 00519.4-5.c

A painter of landscapes populated by merry-making figures, Seldron was admitted into the Brussels painters’ guild in 1702. She was court painter to Maria Elisabeth of Austria, governor of the Southern Netherlands. Seldron continued to paint and sign her work with her own name after marrying sculptor and architect Nicolaas Simons.

Clara Peeters

b. ca. 1587, Mechelen, Belgium; d. after 1636, Ghent, Belgium

A Still Life of Lilies, Roses, Iris, Pansies, Columbine, Love-in-a-Mist, Larkspur and Other Flowers in a Glass Vase on a Tabletop, Flanked by a Rose and a Carnation, ca. 1610

Oil on panel; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay, inv. 2016.30

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Peeters and other artists created detailed floral still lifes, reflecting the growing popular interest in the natural world across artistic and scientific communities. Likely observing her subjects directly from life as well as from published botanical illustrations, Peeters opted for the innovative approach of realism. She presents the flowers overlapping each other and depicts the undersides of some. In contrast, the compositions of her artistic predecessors tended to be idealized and highly stylized.

Maria Sibylla Merian

b. 1647, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; d. 1717, Amsterdam

Der Rupsen Begin, voedzel en Wonderbaare/Verandering (The Birth of Caterpillars, Their Food and Wondrous Transformation), 1713–17

National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, D.C., inv. N44. M561 A5125 1713

This Dutch edition of Merian’s book on the life cycle of caterpillars, a volume she first published in German in 1679 while living in Nürberg, indicates the popularity of her scientifically exacting work in the Dutch Republic, her adopted home. Merian’s documentation of the metamorphoses of butterflies and moths–both written and illustrated–were observed from specimens that she raised for study. While living in Amsterdam, Merian was part of a wide network of artists, collectors, and scientists interested in studying the natural world.

Margareta de Heer

b. before 1603, Leeuwarden, the Netherlands; d. before 1665, Leeuwarden, the Netherlands

Still Life with Flowers and Small Animals on a Ledge, 1642

Transparent and opaque watercolor and black chalk on parchment; The Maida and George Abrams Collection, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Gift of George Abrams in memory of Justice Ruth I. Abrams, Radcliffe ’53, Harvard, Law School ’56, inv. 2023.635

De Heer, like Maria Sibylla Merian and others later in the seventeenth century, used her artistic skills to document the natural world around her. While she also painted other subjects, such as barnyard scenes, much of her extant oeuvre depicts insects including butterflies, moths, and beetles. De Heer’s work and talent were praised in many contemporary poems; and she likely executed work for a botanist in the city of Groningen.

Alida Withoos

b. 1660/62, Amersfoort, the Netherlands; d. 1730, Hoorn, the Netherlands

Forest Floor Still Life with Butterflies and a Lizard, ca. 1700

Oil on canvas; The Maida and George Abrams Collection, Boston

Withoos, like Maria Sibylla Merian, Cornelia de Rijk, and Rachel Ruysch, painted floral still lifes and illustrated specimens. So-called “forest floor” scenes, such as this one, comprised a distinctive genre that was a specialty of her father, artist Matthias Withoos (1627–1703). This painting reflects Withoos’s attention to detail in the distinct foliage of each plant and markings of the butterflies and salamander. Along with other artists, including Merian and her daughter Johanna Helena Herolt, Withoos was commissioned by wealthy naturalist Agnes Block (1629–1704) to record plants she cultivated.

Rachel Ruysch

b. 1664, The Hague, the Netherlands; d. 1750, Amsterdam

Still Life of Flowers, with Butterflies, Insects, a Lizard and Toads, beside a Pool, 1687

Oil on canvas; The Klesch Collection

Ruysch spent her early years surrounded by the scientific collections of her father, the anatomist and botanist Frederik Ruysch (1638–1731), where she became attuned to the power of minute observation. This is reflected in all of her work, including early“forest floor” still-life paintings such as the one on view here. In this composition, Ruysch suffuses her detailed renderings of plants, insects, and amphibians with dramatic tension: the green lizard at the bottom center is about to make a meal out of the unsuspecting butterfly.

Cornelia de Rijk

b. 1653, Delft, the Netherlands; d. 1726, Amsterdam

Fowl in a Garden Landscape, ca. 1685–90

Oil on canvas; Private collection, the Netherlands

De Rijk specialized in depicting fowl. This motif was popular in the late seventeenth century, particularly with the wealthy, for whom hunting was a mark of social status. Her close observation of birds anatomy and plumage—as well as her meticulous drawings of insects—places De Rijk at the intersection of art and science, along with the other artists on view in this gallery.

Clara Peeters

b. ca. 1587, Mechelen, Belgium; d. after 1636, Ghent, Belgium

Left to right:

Still Life with Fish, ca. 1612–21

Oil on panel; Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA)–Flemish Community Collection, Antwerp, inv. 834

Still Life of Fish and Cat, after 1620

Oil on panel; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay, inv. 1986.263

Painting for the first open art market in Antwerp, where buyers could procure finished paintings (instead of having them commissioned), Peeters relied on skill and technique to reproduce her popular imagery quickly. She strategically repeated motifs, such as the carp in the center of each of these paintings. Collectors would have appreciated the verisimilitude with which Peeters depicted varied textures in these seafood still lifes, a genre in which she was a pioneer.

Michaelina Wautier

b. 1614, Mons, Belgium; d. 1689, Brussels, Belgium

Boy with Tobacco, ca. 1650–55

Oil on panel; The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Wautier had a successful studio practice in Brussels alongside her brother Charles Wautier (1609–1703), also an artist. She painted portraits, history paintings, floral compositions, and genre scenes such as this example, likely from a series depicting the five senses. Here, Wautier depicts tobacco, which was imported into Europe from the British colony of Virginia, where it was cultivated on a massive scale through enslaved labor. This painting attests to Wautier’s artistic skill as well as international trade networks that made colonial products commonplace in the Low Countries, affecting nearly every part of daily life.

Unidentified artist

Southern Netherlands, Antwerp

Lace border with cauliflower or peony design, ca. 1650

Linen; On loan from Laurie Waters

As colonial expansion rapidly widened the global trade network, demand for lace grew among wealthy expatriates. This was especially true in the Spanish colonies in the Americas, which led to the shipping of vast quantities of lace from Flanders (and France), traveling overseas via the port of Cádiz. This example is typical of the style of lace that was produced in Flanders by women specifically for export to Spanish colonies.

Cornelia van der Mijn

b. 1709, Amsterdam; d. 1772, London

Still Life with Flowers, 1762

Oil on canvas; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, inv. SK-A-3907

Throughout Van der Mijn’s childhood, her father, painter merman van der Mijn (1684–1741), moved his family to Düsseldort and Antwerp before finally settling in London. There, father and daughter, along with Van der Mijn’s aunt, Agatha van der Mijn (1700–after 1777), also an artist, worked for courtly patrons. The biographer Johan van Gool, who visited the family there, observed that Cornelia van der Mijn “practices art with great fame in London, and has much to do.”

Johanna Vergouwen

b. 1709, Amsterdam; d. 1772, London

Left to right:

Samson and Delilah, 1673

after Anthony van Dyck

Oil on copper; Museo Nacional de San Carlos Collection, INBAL–Secretaría de Cultura, Mexico City, inv. SIGROPAM 9219

The Meeting between David and Abigail, 1673

after Peter Paul Rubens

Oil on copper; Museo Nacional de San Carlos Collection, INBAL–Secretaría de Cultura, Mexico City, inv. SIGROPAM 9132

Vergouwen was a member of the painters’ guild in Antwerp and ran a shop with her older sister, Maria, where they sold paintings on copper, cartoons for tapestries, and other works. These two paintings made by Vergouwen, after well-known compositions by Rubens and Van Dyck, were almost certainly made for export to the Spanish colonies, where merchants specifically requested copies of famous Flemish paintings. Copper was an ideal support for works made for transatlantic transport, as it was more durable than canvas.

Maria de Wilde

b. 1682, Amsterdam; d. 1729, Amsterdam

On screen:

Illustrations of antique sculptures from Signa antiqua e museo Jacobi de Wilde (Ancient Symbols from the Museum of Jacob de Wilde), 1700

In case:

The visit of Tsar Peter the Great on December 13, 1697, to the art cabinet of Jacob de Wilde in Signa antiqua e museo Jacobi de Wilde (Ancient Symbols from the Museum of Jacob de Wilde), 1700

Engraving on paper; National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, D.C., inv. NB71. A47 W55 1700

Like many upper-class women, De Wilde had the opportunity to study and become proficient in many art forms, including music, poetry, drawing, engraving, and painting. For this publication of objects from her father’s art collection, she illustrated fifty-five antique Egyptian, Greek, and Roman sculptures. On the page exhibited here, De Wilde records the visit of Tsar Peter the Great of Russia in 1697 to her father’s renowned art collection.

Maria Sibylla Merian

b. 1647, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; d. 1717, Amsterdam

All from Dissertatio de generatione et metamorphosibus insectorum Surinamensium (Dissertation on Insect Generation and Metamorphosis in Surinam), 1719

Hand-colored engravings on paper; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay, inv. 1986.219

Unlike the stationary and specimen-like depictions of insects by her contemporary, Cornelia de Rijk, Merian’s illustrations of flora and fauna of the Dutch colony of Suriname are teeming with life. Merian, who had previously published illustrated volumes on the metamorphoses of caterpillars, traveled to Suriname in 1699 to observe its ecosystem directly. During her two years there, she was aided in her research by enslaved Africans and Indigenous people. From them, she learned and recorded the local uses of many plants, such as the peacock flower, which has abortifacient properties.

Top, left to right:

Guava tree with Army Ants, Pink-Toed Tarantulas, Huntsman Spiders and a Ruby-Topaz Hummingbird, Plate 18

Pineapple, with the life cycle of a Dido Longwing Butterfly, Plate 2

Bananas with the life cycle of a Teucer Owl Butterfly, and a Rainbow Whiptail Lizard, Plate 23

Bottom, left to right:

Peacock Flower, Plate 45

Pomelo Tree with the Green-Banded Urania Moth and an Unidentified Caterpillar, Plate 29

Cassava Root with a Garden Tree Boa, a Rustic Sphinx Moth, the Caterpillar and Chrysalis of the Tetrio Sphinx Moth and a Treehopper, Plate 5

Maria Moninckx

b. ca. 1676, The Hague, the Netherlands; d. 1757, Amsterdam

Azadirachta indica (Neem), Plate 76 from Horti Medici Amstelodamensis Rariorum, vol. 1, 1697

Hand-colored engraving on paper; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Print collection assembled by Nancy Valentine, purchased with funds donated by Mr. Oliver R. Grace, inv. 2009.90

Known as neem or margosa, Azadirachta indica is a tree native to tropical regions of Asia. Moninckx made this illustration, along with one hundred others, from various specimens being cultivated in Amsterdam at the Hortus Medici (now the Hortus Botanicus). Along with Moninckx and her relative Jan Moninckx, who spearheaded the project, artists including Maria Sibylla Merian, Johanna Helena Herolt, and Maria Withoos contributed illustrations that would eventually be published in nine volumes. Later in the century, this Moninckx Atlas was instrumental to the studies of famed botanist Carl Linnaeus.

Unidentified artist(s)

Southern Netherlands, Brussels

Cover in bobbin lace, point d’Angleterre, 1730–50

Linen; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Albert Blum, 1953, inv. 53.162.45

This work incorporates motifs from the Americas and Asia, such as the palm trees, pineapples, and figures drinking tea at the center and lower corners. Made for the European market, it demonstrates the influence of colonial expansion on myriad designs of the period.

Unidentified artist

Northern Netherlands

Cotton hat with Zaans stitchwork, ca. 1700–50

Embroidered cotton; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Gift of Mrs. Quarles de Quarles-van Ewijck, The Hague, inv. BK 14701

The expansion of enslaved labor in the American colonies resulted in an influx of cotton textiles into the Low Countries, which allowed women working as seamstresses and embroiderers to ply their trade in this material. This cotton child’s cap is embroidered with floral motifs in a technique known as Zaans stitchwork; it would have been more expensive than one made from locally produced linen.

Catharina Backer

b. 1689, Amsterdam; d. 1766, Leiden, the Netherlands

Fan with allegorical scene, before 1711

Oil on leather; Amsterdam Museum, Long-term loan from Foundation Backer, inv. TB 5957

Hand-held fans, which were introduced into Europe from Asia in the sixteenth century, became an increasingly popular accessory toward the end of the seventeenth century. This fan leaf by Backer would have been adhered to carved ivory or bone fan sticks imported from Asia. Her design, however, is distinctly European: a classical garden inhabited by gods, goddesses, putti, and, enthroned on a dais, the allegorical personification of painting, Pictura.

Cornelia de Rijk

b. 1653, Delft, the Netherlands; d. 1726, Amsterdam

Left to right:

Two Butterflies, folios 5 and 6

Four Insects, folios 85 and 86

Two Insects, folios 111 and 112

All from Album of Surinamese Insects, ca. 1703–1710

Gouache over graphite on paper; Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Stockholm, inv. KVA:s bildarkiv

These highly detailed studies of insects by De Rijk, presented as though mounted specimens, are from an album containing more than one hundred drawings of butterflies and beetles from the Dutch colony of Suriname. De Rijk most likely accessed them in the collection of her second husband, Simon Schijnvoet. In turn, Schijnvoet probably procured the collection through De Rijk; her stepson may have brought the specimens back to the Dutch Republic after visiting his sister, who lived in Suriname.

Legacy

While many Flemish and Dutch women artists were acclaimed during their lifetimes, they have largely been forgotten or excluded from art history in the intervening centuries.

Works by women artists, such as paintings, paper cuttings, and lace, were highly sought-after during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. For a variety of reasons, they have been disregarded, misidentified, or neglected from art historical scholarship over time. A traditional artistic hierarchy, which holds representational art such as painting and sculpture at the apex, has long excluded mediums in which women were prominent, such as textile works. However, even paintings, drawings, and prints by women have been commonly misattributed to male artists and overlooked for conservation and research.

Recovering and recognizing Dutch and Flemish women’s artistic contributions provides a fuller appreciation of the past, while also shedding light on forces that have shaped our unbalanced understanding of the period. In recent years, museums and collections have begun to acknowledge past biases and to acquire, exhibit, and preserve work by historical women.

With this renewed interest, the work of more women is being rediscovered, with many more undoubtedly left to find.

Josina Margareta Weenix

b. 1684/85, Amsterdam; d. 1724, Amsterdam

Still Life with Fruit and Vista, ca. 1720–24

Oil on canvas; Museum of Fine Arts (MSK), Ghent, inv. 2023-AT

Weenix belonged to an artistic family: her grandfather Jan Baptist Weenix (1621–ca. 1659) specialized in landscape painting, her father, Jan Weenix (1641–1719), was a still-life painter, and her younger sister, Maria Weenix (1697–1774), was also an artist. Her work has suffered from misattribution, due primarily to the misinterpretation of her signature. It was not until 2020 that her name was linked with a small group of paintings, including this one, which was acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent, Belgium, in 2023.

Judith Leyster

b. 1609, Haarlem, the Netherlands; d. 1660, Heemstede, the Netherlands

Boy Holding Grapes and a Hat, ca. 1629

Oil on panel; Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire, Henry Melville Fuller Fund, inv. 2022.29

Leyster, one of few female members of the painters’ guild in Haarlem, was absent from popular memory within years after her death. Her works, which were misattributed to male artists for two centuries, only began to attract serious scholarly attention in the late twentieth century. This painting was deaccessioned by a U.S. museum in 1977, even though it was known to be by Leyster. While second-wave feminist art historians were beginning to recover the work of historical women artists in the 1970s, it took longer for their work to be valued in museums. In 2022, this painting was acquired by the Currier Museum of Art.

Adriaan Blok

b. ca. 1653, location unidentified; d. 1726, Amsterdam

Het stamboek op de papiere snykunst van Mejuffrouw Joanna Koerten, Huisvrouw van den Heere Adriaan Blok (The “stamboek” of the paper cutting art of Madame Johanna Koerten, wife of Sir Adriaan Blok), Amsterdam, 1735

Houghton Library, Harvard University, Endowment Fund for Donald and Mary Hyde Collection and Arthur and Charlotte Vershbow Book Fund, 2024, inv. 2024-1147

Internationally renowned during her lifetime, Koerten welcomed visitors into her home to view examples of her work. Many wrote short poems of praise and admiration after their visits. Koerten’s fame lasted for a time after her death; her husband, Adriaan Blok, published this collection of laudatory poems written in her honor. Despite her fame, Koerten’s legacy and work faded from popular memory as women artists and the art forms they were associated with were excluded from the art historical canon.

Johanna Koerten

b. 1650, Amsterdam; d. 1715, Amsterdam

Roman Freedom, 1697

Paper cutting; Westfries Museum Collection, Hoorn, inv. 20307

Koerten is one of few paper-cutting artists whose work is still extant today. Roman Freedom exemplifies her technique, with countless thin incisions creating the illusion of volume and depth. She kept this work as a showpiece in her home gallery, where she welcomed admirers. One of her biographers wrote that the Elector Palatine of Germany offered her 1,000 guilders for three works, which she declined. Koerten’s refusal to sell for this enormous sum speaks to her attachment to this work as well as her wealth and status.

Arnold Houbraken

d. 1660, Dordrecht, the Netherlands; d. 1719, Amsterdam

De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (The Great Theatre of the Netherlandish Painters and Paintresses), 1718, Vol. 3

National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, D.C., inv. ND652.H86

Houbraken’s inclusion of Johanna Koerten (pictured here) in his tome of important Dutch and Flemish painters indicates his respect and admiration for her paper-cutting skills. His entry on her extends to a significant length, including nine pages dedicated to a poem in her honor written by the (woman) poet Gezine Brit (1669–1749). Koerten was one of only four women artists to have her portrait illustrated in Houbraken’s first edition and the only one to appear on a page by herself.

Catrina Tieling

b. 1670, Northern Netherlands; d. date and location unidentified

Cows in an Italianate Landscape, ca. 1700

Oil on canvas; Private collection, the Netherlands

Rising interest in Dutch and Flemish women artists over the past fifty years has led to more scholarly attention which, in turn, has led to the identification of more works by women. At least four works by Tieling, who was entirely unknown to art historians until recently, have now been identified; they range from barnyard scenes to landscapes. This painting is particularly important, as it is one of few known Italianate landscapes by women artists of the era, further evidence that women worked across a broad spectrum of genres.

Reproduction of Portrait of Empress Maria Theresa, Sovereign of Austria, Bohemia, and Hungary (1748), by Martin van Meytens (1695–1770)

Unidentified artist(s)

Southern Netherlands

Sleeve fragment of bobbin lace, 1740–50

Linen; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Henrietta Seligman Lace Collection, bequest of Mrs. Jesse Seligman, 1910, inv. 10.102.31

In 1744, the Flemish city of Ghent commissioned local lacemakers—possibly residents of an orphanage—to make a lace dress for Empress Maria Theresa, then governor of Flanders. It was meant to fulfill, in part, back taxes owed to the Habsburg court. It took numerous lace makers five months to create, and it was valued at 25,000 guilders, an astonishing sum (annual wages were a few hundred guilders). Maria Theresa commissioned at least two full-length portraits of herself wearing the gown, as seen in the reproduction nearby. While the dress is no longer extant, this sleeve fragment is likely its only surviving remnant.

Nicolaas Juweel

b. ca. 1639, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; d. 1704, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Watching a Paper-Cut Wind Toy, ca. 1697

Oil on canvas; London College of Optometrists, inv. LDBOA1999.178

Created by both men and women, paper cuttings were popular and costly art objects of the period. Women artists Johanna Koerten (1650–1715), and Elisabeth Rijberg (active 1698–1710) were two of the most celebrated paper-cutting artists in the Dutch Republic. Due to the medium’s fragility, as well as its historical exclusion from the canon of “high” art, many examples, such as the three-dimensional work pictured here, have not survived. While the older woman in this painting has not been identified, she may be another paper artist or collector of such works.

Catarina Ykens I or Catarina Ykens II

Catarina Ykens I b. 1615, Ghent, Belgium; d. after 1665, Antwerp

Catarina Ykens II b. 1659, Antwerp; d. after 1689, Antwerp

Portrait of a Woman Playing the Guitar, Surrounded by a Garland of Fruit and Flowers, ca. 1660–80

Oil on panel; Private collection

Works by women are becoming more popular to acquire—both by collectors and museums—as individuals and institutions learn about recent research into historical women artists and seek to broaden their collections. This painting has been attributed to both Ykens I and Ykens II, who, in addition to being related and sharing a name, also had similar painting styles. More research into these artists is needed to clarify their respective oeuvres.

Unidentified artist(s)

Southern Netherlands

Benediction veil in bobbin lace, ca. 1750–90

Linen; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Albert Blum, 1953, inv. 53.162.46

Textiles such as lace, some of the most expensive items to purchase in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, are, today, often valued less than works such as paintings. This devaluation is evident in their sales prices in the art market as well as their lack of visibility within art historical scholarship and many museum collections. Women can be credited with preserving lace for posterity, too. For example, women assembled many of the most important lace collections in U.S. museums. Without their efforts, much of the cultural legacy of lacemaking might have been lost.

Rachel Ruysch

b. 1664, The Hague, the Netherlands; d. 1750, Amsterdam

Roses, Convolvulus, Poppies and Other Flowers in an Urn on a Stone Ledge, ca. 1680

Oil on canvas; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay, inv. 1986.282

Works by Ruysch, one of the most successful floral still-life painters of her day, were acquired by wealthy collectors including European royalty. While many women’s legacies faded quickly after their lifetimes, sales data from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries demonstrate that Ruysch’s works remained popular. Despite this persistence, Ruysch is rarely represented in the collections of major museums, and she was omitted from much twentieth-century scholarship. In 2024, however, the first major exhibition of her work opened. The milestone marks her importance within the genre, which demanded artistic talent along with scientific accuracy.

Catharina Backer

b. 1689, Amsterdam; d. 1766, Leiden, the Netherlands

Drawing album, 1706–22

Amsterdam Museum, Long-term loan from Foundation Backer, inv. TB 5955

Backer, whose portrait and works are on view throughout this exhibition, grew up in a wealthy family with a home full of art. This carefully preserved album of sketches and finished drawings is evidence of Backer’s dedication to her practice as well as the importance she and her heirs ascribed to it. Among the drawings in this album are nude figures, such as the ones shown here, which were likely copied by Backer from other sources, such as sculptures or prints.

Willem Beurs

b. 1656, Dordrecht, the Netherlands; d. ca. 1700, Zwolle, the Netherlands

De groote waereld in ’t kleen geschildert (The Great World Painted in Small), 1692

National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, D.C., inv. ND1471. B48

Artist Aleida Greve (1670–1742), her half-sister Cornelia van Marle (1661–1698), and her cousins Anna Cornelia Holt (1671–before 1706) and Sophia Holt (1658–1734) were instructed by the painter Willem Beurs. His admiration for his students is evident in this 1692 handbook for beginning artists, in which he calls them “my highly esteemed and beloved pupils, my delight and crown.”

In 1706, artist Aleida Greve (1670–1742) and her sisters purchased this house from Pieter Soury, mayor of Zwolle, and his wife, the painter Aleida Wolfsen (1648–1692). Greve decorated it with her paintings and those of her fellow students. She stipulated in her will that the house and its contents be preserved as a charitable residence for elderly widows and unmarried women, which it was for nearly two centuries. Today, it is the Vrouwenhuis Museum (Women’s House Museum), a monument to the lives and works of these women artists.

Exterior of the Vrouwenhuis Museum in Zwolle, the Netherlands

Photo by Saskia Zwiers

Attributed to Antonina Houbraken or Jacobus Stellingwerf

Antonina Houbraken b. 1686, Dordrecht, the Netherlands; d. 1736, Amsterdam

Jacobus Stellingwerf b. 1667, Amsterdam; d. 1727, Amsterdam

Castle of Egmond op den Hoef, Holland, 1702

Pen and black ink, with gray wash; framing line in black ink; Victoria and Albert Museum, London, inv. E.1869-1920

Houbraken was the daughter of writer and artist Arnold Houbraken (1660–1719), known for his publication of artists’ biographies. Among her other works, she made more than a thousand topographical drawings for a patron compiling an atlas of the Dutch Republic. This drawing demonstrates the complexity of studying historical women artists, as it bears the signature “J. Stellinghwerf [sic],” the name of Houbraken’s husband. Recent research has shown that Houbraken signed her work with her husband’s name during their marriage and was likely his instructor in the art of drawing.

Maria Tassaert

b. 1642, Antwerp; d. after 1665

Still Life with a Garland of Fruits, ca. 1660–65

Oil on canvas; The Henry Barber Trust, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham, inv. 2022.1

Tassaert’s refined technique, which displays a masterful quality of illusionism, and prominent signature at the bottom left indicate that she worked as an independent artist. This painting is one of just two currently attributed to Tassaert, both recently discovered, and her legacy is only now coming into focus. The daughter of landscape painter Pieter Tassaert (d. ca. 1692) and niece of Catarina Ykens I (1615–after 1665), Tassaert developed her talents in a close-knit artistic family.

Choices

The options available to women artists—whether to marry, whether to pursue specialized training, and much more—depended foremost on the social class and family they were born into.

Women in artistic or wealthy families generally had access to more opportunities. Those who were born into families of painters or printmakers, for example, would often be trained in that medium and given a role within the family workshop. Middle- and upper-class women could study with professionals to hone their skills. Lower-class girls and women usually had no choice but to work, and many produced textiles such as lace, often as domestic workers, in orphanages, or in correctional institutions.

Marriage and childbearing also shaped the course of women’s lives, though its effects, again, were dependent on social class: those with the means to hire domestic help were more likely to continue their work, while others found that domestic responsibilities left little time for their art. Some women who joined religious orders or remained unmarried found independence to continue their artistic pursuits.

Johannes de Maré

b. ca. 1640, Antwerp; d. 1709, Antwerp

Portrait of Franciscus van Hildernissen and His Wife Catherina de Coninck and Orphans in the Maidens’ House, 1676

Oil on canvas; Maagdenhuis, Antwerp, inv. A178

In the room behind the portraits of the patrons of the Maagdenhuis (Maidens’ House) in Antwerp, dozens of girls are hard at work. Charitable institutions such as this one provided homes for lower-class and orphaned girls as well as training in skills for work. While reading and writing were part of the curriculum, priority was often given to the production of textile goods such as lace and embroidery, which could be sold for profit. The central group of girls focus on needlework on sewing cushions on their laps. A group in the top left corner is making lace, while a smaller group in the top right sits with books opposite a man, presumably their schoolteacher.

Aleida Wolfsen

b. 1648, Zwolle, the Netherlands; d. 1692, Zwolle, the Netherlands

Left to right:

Portrait of Johannes Battista Bartolotti van den Heuvel, Lord of Rijnenburg and Hoeckenburg, ca. 1677–83

Oil on canvas; Museum Arnhem, inv. GM 02066

Portrait of Gertruida Dorothea van Goltstein, ca. 1677–83

Oil on canvas; Museum Arnhem, inv. GM 02065

Although she lived in various cities in the Dutch Republic, Wolfsen is most closely associated with Zwolle. She was the daughter of the mayor of the city and later married another mayor. Wolfsen moved in elite social circles, and her portraits, like these, depict members of the upper class. She may have studied with Caspar Netscher (1639–1684), who in turn studied with Gerard ter Borch the Younger (1617–1681), brother of Gesina ter Borch, who also resided in Zwolle and whose work is on view nearby.

Gesina ter Borch

b. 1631, Deventer, the Netherlands; d. 1690, Zwolle, the Netherlands

Top to bottom:

Interior with Three Soldiers Smoking and Drinking, ca. 1654

Chalk and ink on paper; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, inv. RP-T-1887-A-1286

The Homeward-coming Couple, 1655

Pen and black ink, watercolor, and bodycolor on paper; Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, inv. GesT 1 (PK)

Ter Borch was raised in a family of artists led by her father, Gerard ter Borch the Elder (1583–1662). She made oil paintings as well as drawings and watercolors on paper such as these. Her works often have a particularly intimate character, focusing on themes including love, passion, and death. Ter Borch’s work mainly circulated within the private sphere of family and friends. She is also known to have collaborated on paintings with her brother, Gerard ter Borch the Younger (1617–1681).

Magdalena van de Passe

b. 1600, Cologne, Germany; d. 1638, Utrecht, the Netherlands

Portrait of Katherine Villiers (née Manners), Duchess of Buckingham, ca. 1620–23

Engraving on paper; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Rosenwald Collection, inv. 1951.11.266

Like many other women printmakers, Van de Passe learned her trade from her family. Most of her works are reproductions of paintings by well-known artists of the day. She also, however, executed a few portraits of famous international figures, including this image of Katherine Villiers, Duchess of Buckingham. The surrounding illustrations were done by her brother, Willem van de Passe (1597/8–1636/7).

Magdalena van de Passe

b. 1600, Cologne, Germany; d. 1638, Utrecht, the Netherlands

Portrait of Katherine Villiers (née Manners), Duchess of Buckingham, ca. 1620–23

Engraved copper plate; Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, inv. Rawl.Copperplates g.140

This is the copper plate onto which Van de Passe engraved her portrait of Katherine Villiers, Duchess of Buckingham. Plates of this type rarely survive, and this is even more exceptional due to the back: in the unmistakable hand of a child, there is an attempt to replicate the portrait on the front. While Van de Passe did not have children of her own, she was likely surrounded by nieces and nephews in the family workshop. One of them might have been experimenting, perhaps with the assistance of the artist herself.

Unidentified artist

A Young Woman Drawing, 17th century

Oil on canvas; Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson Collection, 1917, inv. 506

This intimate painting of a young woman drawing a figure with chalk illustrates the type of training sometimes afforded to middle and upper-class women. Learning to draw was a foundational skill for artists and an essential part of their training. The first step was to copy two-dimensional models, such as paintings or prints. Students were then permitted to draw from three-dimensional examples, such as original sculptures or plaster models.

Catharina Backer

b. 1689, Amsterdam; d. 1766, Leiden, the Netherlands

Left to right:

Study of Feet and Hands, 1706–22

Red chalk on paper; Amsterdam Museum, Long-term loan from Foundation Backer, inv. TB 6533.43

Study of Feet, 1706–22

Red chalk on paper; Amsterdam Museum, Long-term loan from Foundation Backer, inv. TB 6533.19

While it is commonly assumed that women of this period were rarely trained in drawing the human figure, these studies of feet and hands demonstrate that some were, including Backer, who was from a wealthy family. Her teacher has not been identified, but her sketchbook contains several anatomical studies as well as sketches of sculptures and reliefs (possibly after objects in her father’s art collection), which enabled Backer to experiment with representing nudes.

Catarina Ykens I

b. 1615, Ghent, Belgium; d. after 1665, Antwerp

Still Life with Flowers and Insects, ca. 1660

Oil on canvas; The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Catarina Floquet, also known as Catarina Ykens I, was married to Frans Ykens (1601–1693), who also specialized in still lifes. She was the daughter of a painter from Antwerp who most likely trained her, along with her three brothers. She is identified as Ykens I to differentiate her from another artist, Catarina Ykens II, to whom she was related through marriage, evidence of the close-knit relationships between artistic families.

Rachel Ruysch

b. 1664, The Hague, the Netherlands; d. 1750, Amsterdam

Still Life with Flowers, ca. 1700–50

Oil on canvas; Collection of George M. and Linda H. Kaufman

Ruysch and her younger sister Anna (1666–after 1741) were trained by the renowned Amsterdam still-life painter Willem van Aelst (1627–1683). The sisters belonged to a wealthy upper-middle-class family: they were daughters of the prominent Amsterdam physician and scientist Frederik Ruysch (1638–1731), granddaughters of Pieter Post (1608–1669), court architect to the House of Orange in The Hague, and relatives of Haarlem painter Frans Post (1612–1680). These family connections likely provided models for a successful artistic career for Ruysch.

(Video Label)

Lacemaking demonstration

Video, 1 min.; Courtesy of Elena Kanagy-Loux

This time-lapse video shows lacemaker Kanagy-Loux using twenty bobbins to make an eight-inch length of lace, a nearly eleven-hour project. Bobbin lace developed out of multistrand braiding techniques that increased in complexity, which necessitated winding threads onto bobbins to keep them organized. Pairs of cylindrical bobbins—typically made of wood or bone—are hung onto pins on a firm base and moved over and under each other in the cross direction (left over right) or twist direction (right over left) to create an endless variety of patterns.

Unidentified artist(s)

Southern Netherlands, Brussels

Benediction veil in bobbin lace, 1745–60

Linen; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1938, inv. 38.53

In Flanders, lace production was centered around workshops and schools, often led by Beguines (religious laywomen) who lived and worked in small communities. Veils such as this one may have been used to cover the table on which the Eucharist was placed for benediction, or blessing, during Catholic Mass.

Quiringh van Brekelenkam

b. after 1622, Zwammerdam, the Netherlands; d. after 1669, Leiden, the Netherlands

Interior with a Woman Teaching Three Girls Lacemaking, 1654

Oil on panel; Private collection

All women, regardless of social class, were expected to be proficient in the domestic tasks of spinning, sewing, and embroidery. This training could also extend to lacemaking, which was a much more complex process. As such, some women held “schools” where girls could be trained in this skill if they could not be taught in their own households. The girls here might have used their skills for their own purposes, for supplemental income, or as domestic workers in wealthy homes.

Princess Louise Hollandine of the Palatinate

b. 1622, The Hague, the Netherlands; d. 1709, Val-d’Oise, France

Self-Portrait as a Benedictine Nun, ca. 1665–75

Oil on canvas; Private collection, through the Hoogsteder Museum Foundation, The Hague

Louise Hollandine, whose earlier portrait hangs in the “Presence” section of this exhibition, left her courtly life in The Hague in 1657 and went to France, where she converted to Catholicism and became prioress of Maubuisson Abbey in 1664. She continued to paint there, as she, like many other women, found more freedom to pursue her art within a convent.

Catarina Ykens II

b. 1659, Antwerp; d. after 1689, Antwerp

Left to right:

Garland with a Landscape, ca. 1680–1700

Oil on canvas; Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, inv. P001902

Garland with a Landscape, ca. 1680–1700

Oil on canvas; Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, inv. P001903

Ykens II was the daughter of sculptor and history painter Jan Ykens (1613–after 1680), who provided her initial training. She was also a filiae devotae, or “spiritual daughter,” a woman who took a vow of chastity and devoted herself to a spiritual life. Poised between the religious and the worldly, women such as Ykens II found some autonomy in this role. The central landscapes in these works are by another (unidentified) artist, indicating that Ykens II collaborated with a colleague or sold her paintings before the landscapes were added.

Anna Maria van Schurman

b. 1607, Cologne, Germany; d. 1678, Wieuwerd, the Netherlands

French translation of the New Testament, ca. 1625–75

Embroidered book binding; Museum Martena, Franeker, inv. S0016

Portrait of Eva van Harf, ca. 1632–37

Palm wood; Museum Martena, Franeker, inv. S0016

Carving and embroidery were just two of the many art forms Van Schurman practiced, along with painting, drawing, printmaking, glass etching, and more. Here, she carved a likeness of her mother, Eva van Harf, and embroidered floral designs on a book cover for a small volume of the New Testament using techniques such as cross stitch and French knots. The worn and frayed edges indicate constant use.

Catharina Backer

b. 1689, Amsterdam; d. 1766, Leiden, the Netherlands

Top:

Trollius, Tulip and Soapwort, 1706–22

Oil and pencil on paper; Amsterdam Museum, Long-term loan from Foundation Backer, inv. TB 5932

Bottom:

Cabbage Roses and Sorrel, 1706–22

Oil on paper; Amsterdam Museum, Long-term loan from Foundation Backer, inv. TB 5934

Right:

Opium Poppy and Variegated Sage, 1706–22

Oil and pencil on paper; Amsterdam Museum, Long-term loan from Foundation Backer, inv. TB 5931

While her sketchbook, also on view in this exhibition, demonstrates that Backer’s training included anatomical drawings and studies after classical sculptures (a common practice), her surviving oil paintings are floral still lifes. These highly finished paintings on paper might be studies for larger compositions or considered finished works. Backer’s wealthy family, particularly her father, encouraged her aptitude for art, ensuring that she received training and frequently enjoining her to paint more.

Judith Leyster

b. 1609, Haarlem, the Netherlands; d. 1660, Heemstede, the Netherlands

The Concert, ca. 1633

Oil on canvas; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay, inv. 2001.146

Leyster was a member of the Haarlem painters’ guild. This allowed her to operate a studio and sell her paintings in the city, where there was a large market for the genre scenes in which she specialized. Here, Leyster used herself as the model for the central figure, who leads her companions in song. Her future husband, the artist Jan Miense Molenaer (1609/10–68), appears as the figure in red at the right, playing a lute.

Maria de Grebber

b. 1602, Haarlem, the Netherlands; d. 1680, Enkhuizen, the Netherlands

Portrait of Augustinus de Wolff, 1631

Oil on panel; Museum Catherijneconvent, Utrecht, inv. BMH s151

From one of the most prominent artistic families in Haarlem, De Grebber was trained by her father, Frans Pietersz de Grebber (1573–1649), alongside her brothers Pieter and Albert. Her father may also have been an early teacher to Judith Leyster. This portrait, today the only confirmed work by De Grebber, features her brother-in-law, a Catholic clergyman. It attests to her skill in conveying details of light and texture, particularly in the sitter’s face and beard.

Geertruydt Roghman

b. 1625, Amsterdam; d. 1651/57, Amsterdam

Top, left to right:

A Woman Cooking and A Woman Doing Housework, from the series “Five Feminine Occupations,” ca. 1640–57

Bottom, left to right:

Two Women Sewing and A Woman Spinning, from the series “Five Feminine Occupations,” ca. 1640–57

Engraving on paper; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1956, inv. 56.550.

In this series, Roghman depicts women in the acts of sewing, cooking, cleaning, and spinning, all typical activities in the maintenance of a tidy and productive household. Whether these women are employed for wages or are in their own homes is not certain, but Roghman’s images capture the physical labor of household work: bent over and intent on their tasks, her subjects stand in contrast to the many idealized depictions of such work in paintings of the time.

Nicolaes Maes

b. 1634, Dordrecht, the Netherlands; d. 1693, Amsterdam

The Lacemaker, ca. 1656

Oil on canvas; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Friedsam Collection, bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931, inv. 32.100.5

This quiet scene of a woman making lace in a domestic interior, while not inaccurate in depicting a place where lace might be made, belies the fact that much lace of the time was made by lower-class women and girls in institutions including orphanages and houses of reform. Tranquil scenes such as this one were a popular subject in painting at the time and reinforced social expectations of virtuous housekeeping work for women.

Anna Maria de Koker

b. 1666, Amsterdam; d. 1698, Amsterdam

The Road to the Village, ca. 1680–90

Etching on paper; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1917, inv. 17.31.9

Nothing is known about De Koker’s artistic practice or training except that all of her extant works are landscape prints such as this one. From an extremely wealthy family, De Koker likely produced work for her personal enjoyment. One poet at the time praised her accomplishments in art as well as music.

Catharina Questiers

b. 1631, Amsterdam; d. 1669, Amsterdam

Left to right:

A Woman Appears Before a King on His Throne, an illustration for her play “De geheymen Minnaer,” 1655

Etching on paper; The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: The Print Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations, Samuel Putnam Avery Collection, inv. MEZAT 114836 Grolier 383

A Young Man Kneeling Before a Young Woman, plate from her poem “Van de Koddige Olipodrigo,” 1655

Etching on paper; The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: The Print Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations, Samuel Putnam Avery Collection, inv. MEZAT 112876 Grolier 382

Questiers was a successful playwright and poet whose works were performed in public to great acclaim. Also a visual artist, she often illustrated her own works. Questiers married later in life—at the age of thirty-four—specifically because she did not want to give up her freedom to create. Indeed, no work by her survives from the period after her marriage.

Magdalena Roghman

b. 1637, Amsterdam; d. date and location unidentified

Frontispiece from Jan Bara’s Herstelde vorst, ofte Geluckigh ongeluck, Amsterdam, 1650

Houghton Library, Harvard University, Robert A. Magowan Fund for English Literature, 1977, inv. GEN*EC.Sh154.Ep650b

This publication is a retelling of Shakespeare’s Hamlet in Dutch and contains the only two known engravings by Magdalena Roghman. Born into a family or printmakers, she and her sister, Geertruydt, were trained in the art of engraving by their father, Hendrick Lambertsz Roghman (1602–1647/1657), along with their brother, Roelant, who was also a painter. Many women printmakers were part of large family studios.

Maria van Oosterwijck

b. 1630, Nootdorp, the Netherlands; d. 1693, Uitdam, the Netherlands

Bouquet of Flowers and Fruit with Blue Ribbon, ca. 1680

Oil on canvas; Art Institute of Chicago, Rhoades Foundation and Julius Lewis Acquisition Endowment Fund; Josephine and John J. Louis Jr. Endowed Acquisition Fund; C. Harker and Mae Svoboda Rhodes Acquisition Fund; John A. Bross Fund in memory of Louise Smith Bross, inv. 2022.1437

Van Oosterwijck’s father, who was not an artist himself, but a minister, encouraged her talent for painting. Through extended family, she was in contact with other artists, and she apprenticed with still-life painter Jan Davidsz de Heem (1606–1684) in Utrecht before moving to Amsterdam. There, Van Oosterwijck lived and worked as a respected and sought-after painter, even training one of her maids, Geertgen Wyntges (1636–1712), in the art of painting. Van Oosterwijck remained unmarried throughout her life.

Judith Leyster

b. 1609, Haarlem, the Netherlands; d. 1660, Heemstede, the Netherlands

The Last Drop (The Gay Cavalier), ca. 1629

Oil on canvas; Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson Collection, 1917, inv. 440

Leyster specialized in dramatically lit scenes of small groups of people, which likely sold well and ensured a steady income. Here, two revelers are smoking and drinking, accompanied by a grinning skeleton that holds an hourglass in one hand and cradles a skull and candle in the other. Its ambiguous moralizing message about the brevity of life would have entertained viewers. Leyster’s use of chiaroscuro, or the contrast of lights and darks, was also a popular stylistic device of the period.

Magdalena van de Passe

b. 1600, Cologne, Germany; d. 1638, Utrecht, the Netherlands

Salmacis and Hermaphroditus, 1623

after Jacob Symonsz Pynas

Etching and engraving on paper; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay, inv. 2005.77

Born into a family of engravers, Van de Passe began signing her prints when she was only fourteen. She was admired for her landscapes featuring mythological scenes, which were copied after paintings by other artists. She dedicated this scene from Ovid’s Metamorphoses to Jacob Cats, a Dutch writer who espoused the virtues of marriage. The story of the nymph Salmacis, who assaulted Hermaphroditus and thereby fused their bodies into one with both male and female characteristics, symbolized ideal marriage.

Susanna van Steenwijck-Gaspoel

b. after 1602, London; d. 1664, Amsterdam

Lutheran Cabinet from the Nijenburg Estate, ca. 1660–80

Oil on wood and marquetry; Stedelijk Museum, Alkmaar, inv. 30757

Van Steenwijck-Gaspoel decorated this tabletop cabinet in a variety of different genres: a floral still life appears when all the drawers are closed, a scene on the inside of the hinged door depicts the biblical story of Christ and the Samaritan woman, and an architectural painting of the interior of a church appears in the bottom drawer. The rest of the drawers contain portraits of prominent religious reformers such as John Calvin and Martin Luther.

Johanna Helena Herolt

b. 1668, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; d. after 1723, Suriname

Left to right:

Two Irises (Iris latifolia), a Grape Hyacinth (Muscari botryoides) and a Tuberose (Polyanthes tuberosa), ca. 1700

Watercolor and bodycolor on vellum; Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, Virginia

Crown Imperial (Fritiallaria imperialis), Two Wild Hyacinths (Scilla non-scripta) and Insects, ca. 1700

Watercolor and bodycolor on vellum; Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, Virginia

Trained by her mother, Maria Sibylla Merian, who used her artistic talent to record her observations of the natural world, Herolt likewise made detailed renderings of flora and fauna. Visual art was inextricably linked with the growing fields of botany and biology, and women including Merian and Herolt worked at this intersection, creating images that were scientifically accurate as well as aesthetically pleasing.

Maria Sibylla Merian

b. 1647, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; d. 1717, Amsterdam

On the wall:

A Green Plover, ca. 17th–18th centuries

Watercolor on vellum; Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Bequest of Frances L. Hofer, inv. 1979.225

Maria Sibylla Merian

b. 1647, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; d. 1717, Amsterdam