Hung Liu: Making History

Adapting motifs and symbols from Chinese visual and cultural traditions, as well as antique photographs of Chinese society by Western observers, Liu transformed documentary-style photography into painterly, personal reflections on canvas and paper.

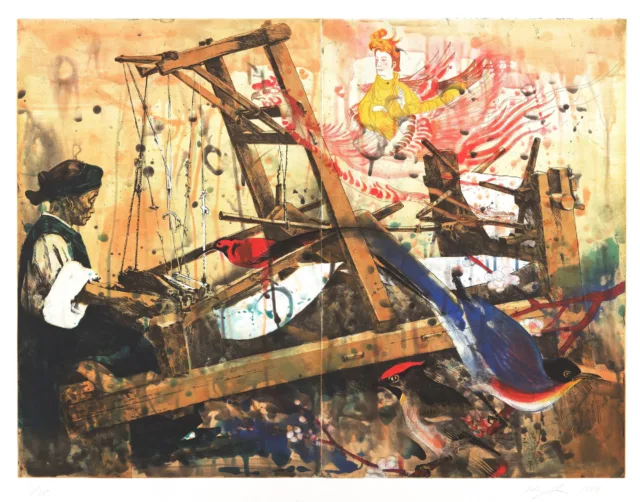

Hung Liu, Women Working: Loom, 1999; Softground etching, spitbite aquatint with scraping and burnishing on paper, 31 1/2 x 41 3/4 in.; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Steven Scott, Baltimore, in memory of the artist and in loving memory of his grandmother, Anna Kemper Albert; © 2023 Hung Liu Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Hung Liu (1948 to 2021)

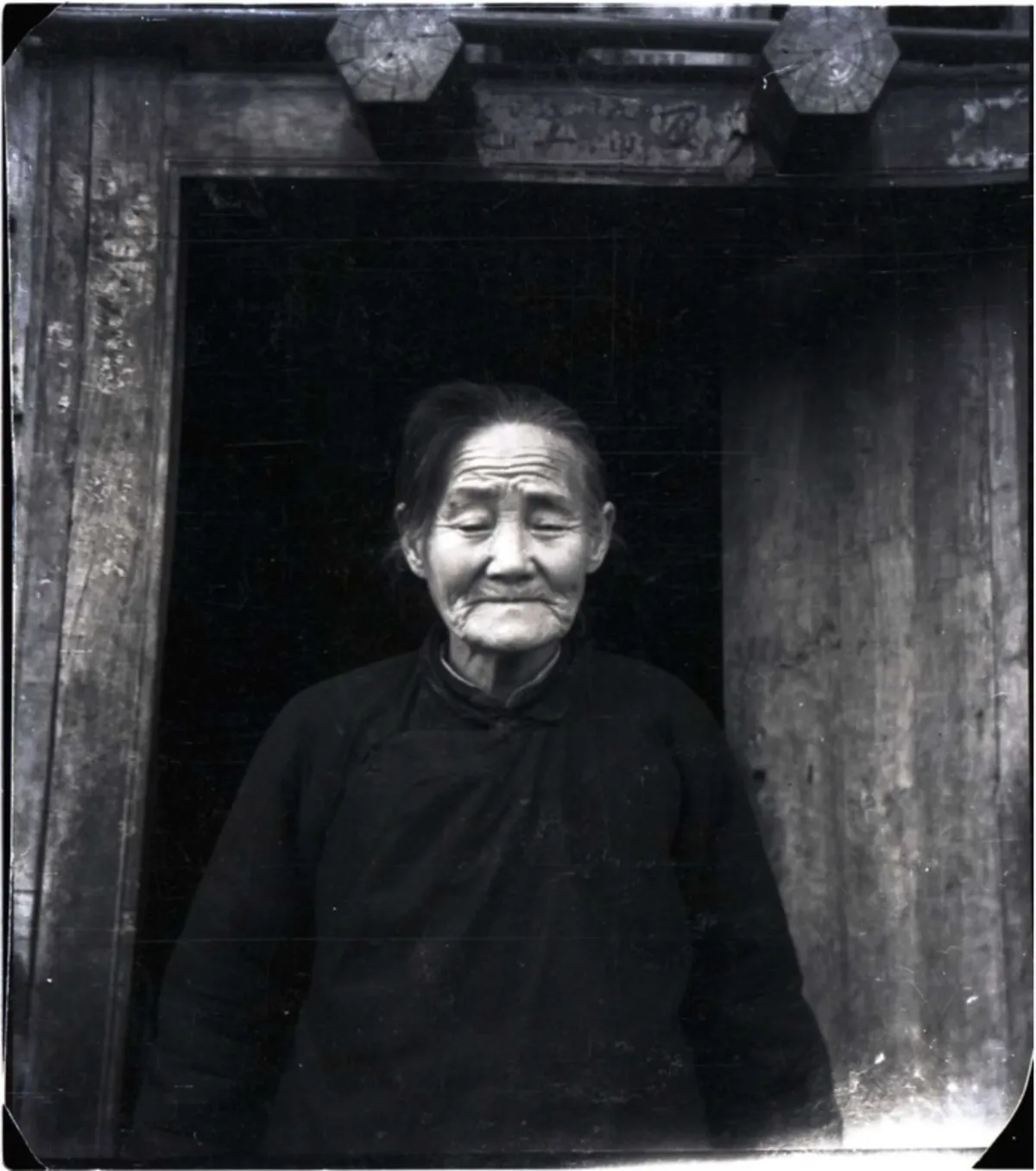

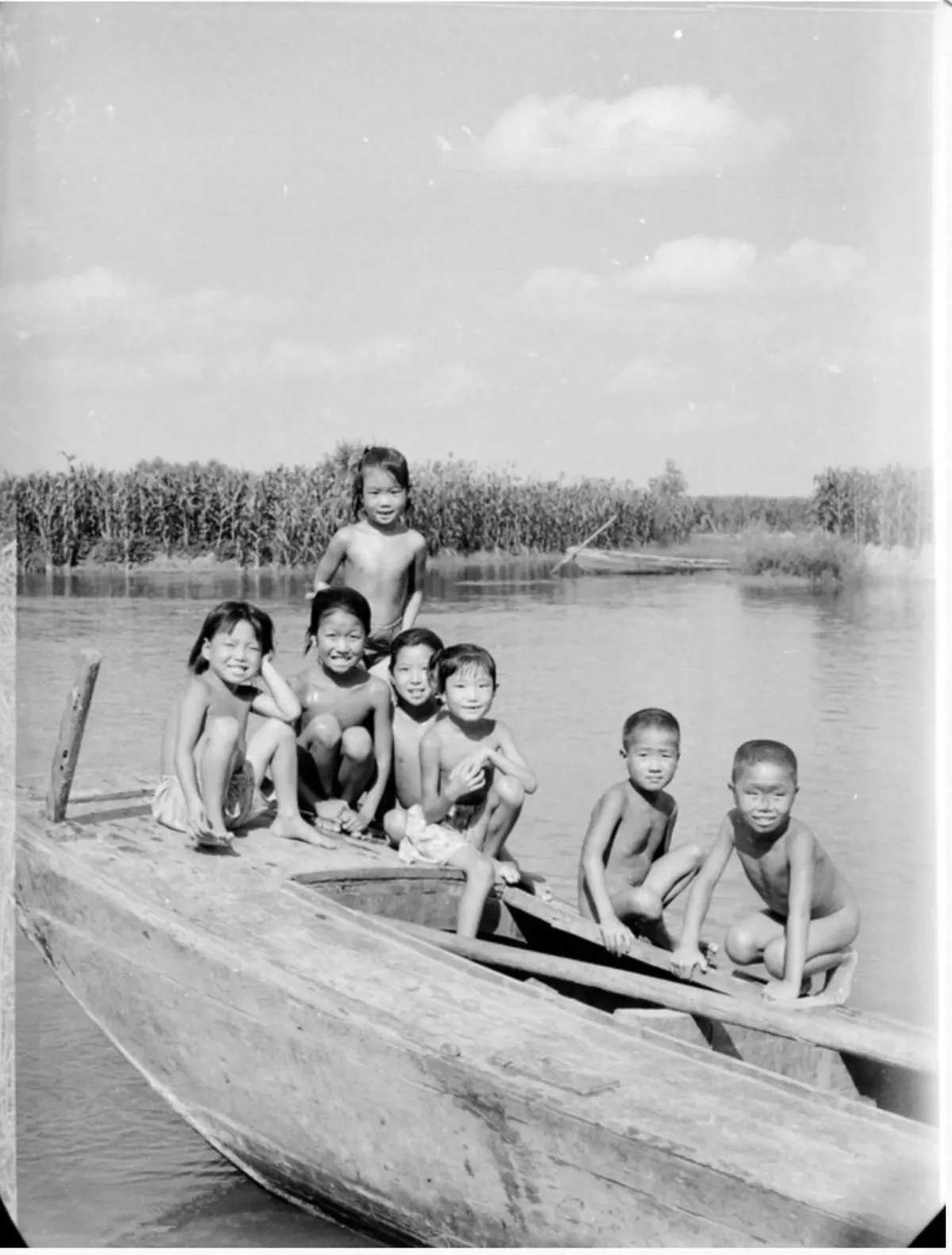

Coming of age during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, Hung Liu (1948 to 2021) was profoundly affected by the plights of the poor and oppressed. Photography played a critical role in the artist’s life and career, from candid shots that she took of villagers in the countryside to the 19th-century portraits of women that became source imagery for her works. She was even inspired by Dorothea Lange’s images of the American Dust Bowl. Liu’s own poetic imagery stirs a collective memory of her country while re-centering the narrative on the most vulnerable in society.

Portraits of Women

Liu’s art has always focused on the human condition, particularly that of women under male-dominated regimes. Her archives of source materials include photographic portraits of empresses, mistresses, laborers, and migrant women. Many of these photographs were hidden in the Beijing Film Studio during the Cultural Revolution. Liu took snapshots of the photographs to bring the images back to the United States, where she had moved in 1984 to continue her art training.

Photographs of Women

Use the left and right arrow keys to navigate through the slides.

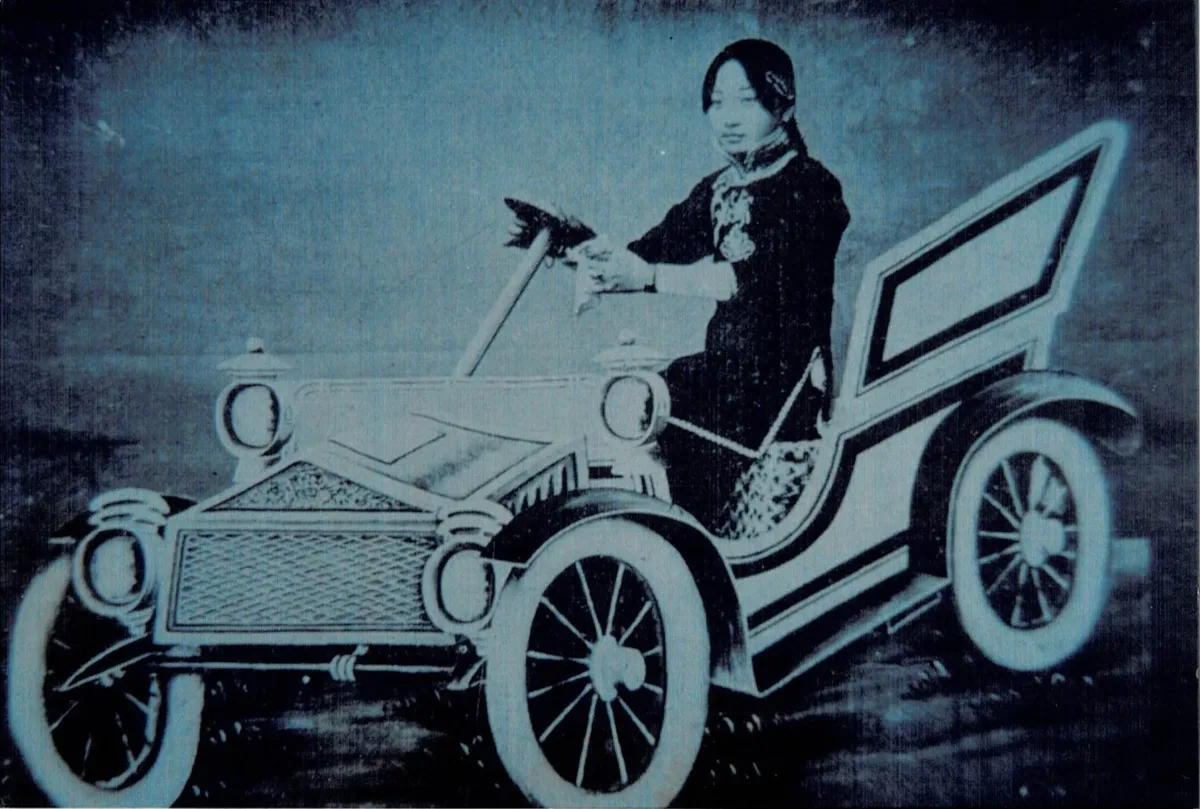

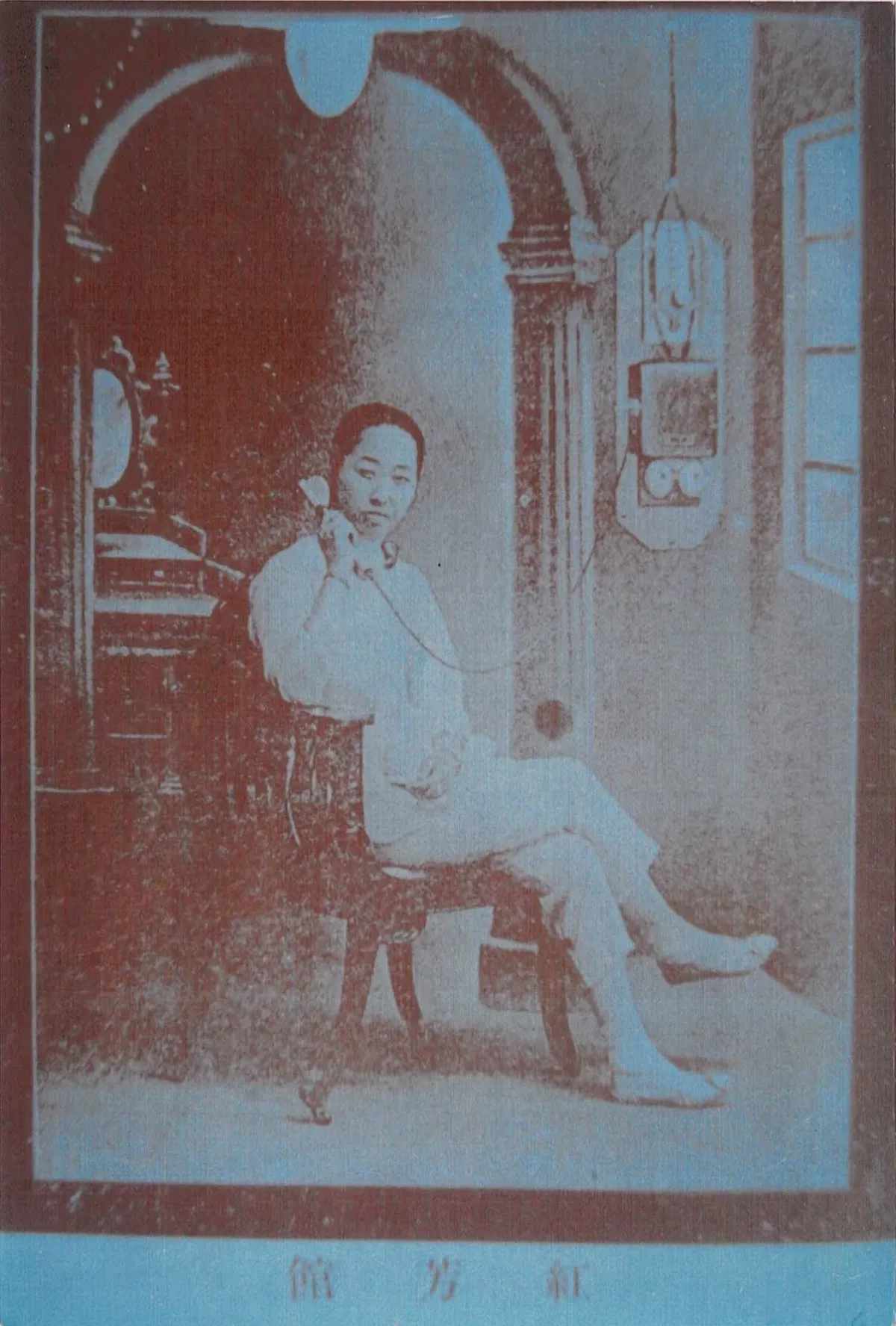

For many of her portrayals of sex workers and courtesans, Liu worked from photographs of Chinese women posed in Western costumes and on stage sets that were dated around 1900. She discovered these photographs on a return visit to China in the 1990s. The attire, props, and backdrops indicate that the archival photographs were intended for Western and upper-class Chinese clientele, while Japanese captions on some of the photographs suggest that they were also meant for Japanese tourists in China.

Anonymous Faces

Shui Water is adapted from a historical photograph of a woman sitting on a railing and surrounded by flowerpots. Liu isolates the figure, placing her in front of a backdrop that evokes Chinese landscape paintings. Her body, layered under streaks of brown earth, may refer to the exploitation endured by working-class women.

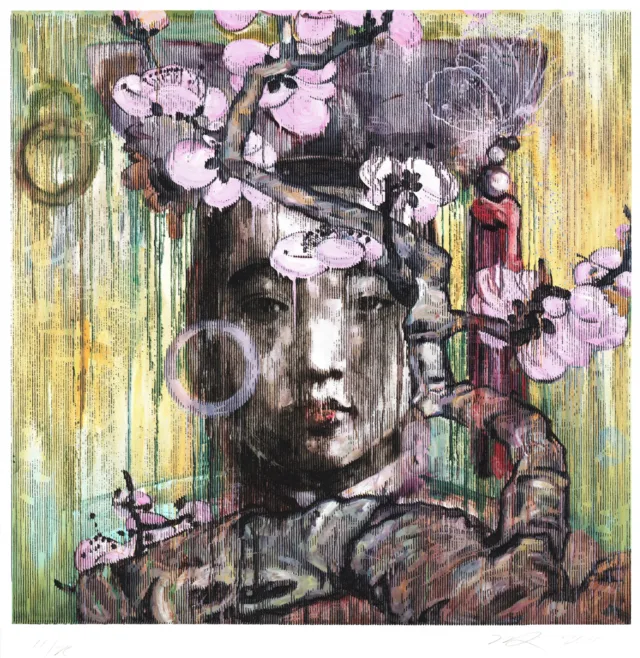

Imperial Women

Liu captures the direct, unflinching gaze of the Imperial Consort Zhen Fei (1876 to 1900), even including her elaborate tasseled headdress. But in Liu’s interpretation, Zhen Fei, who died mysteriously and tragically, is encircled by plum blossoms, a sign of fortitude.

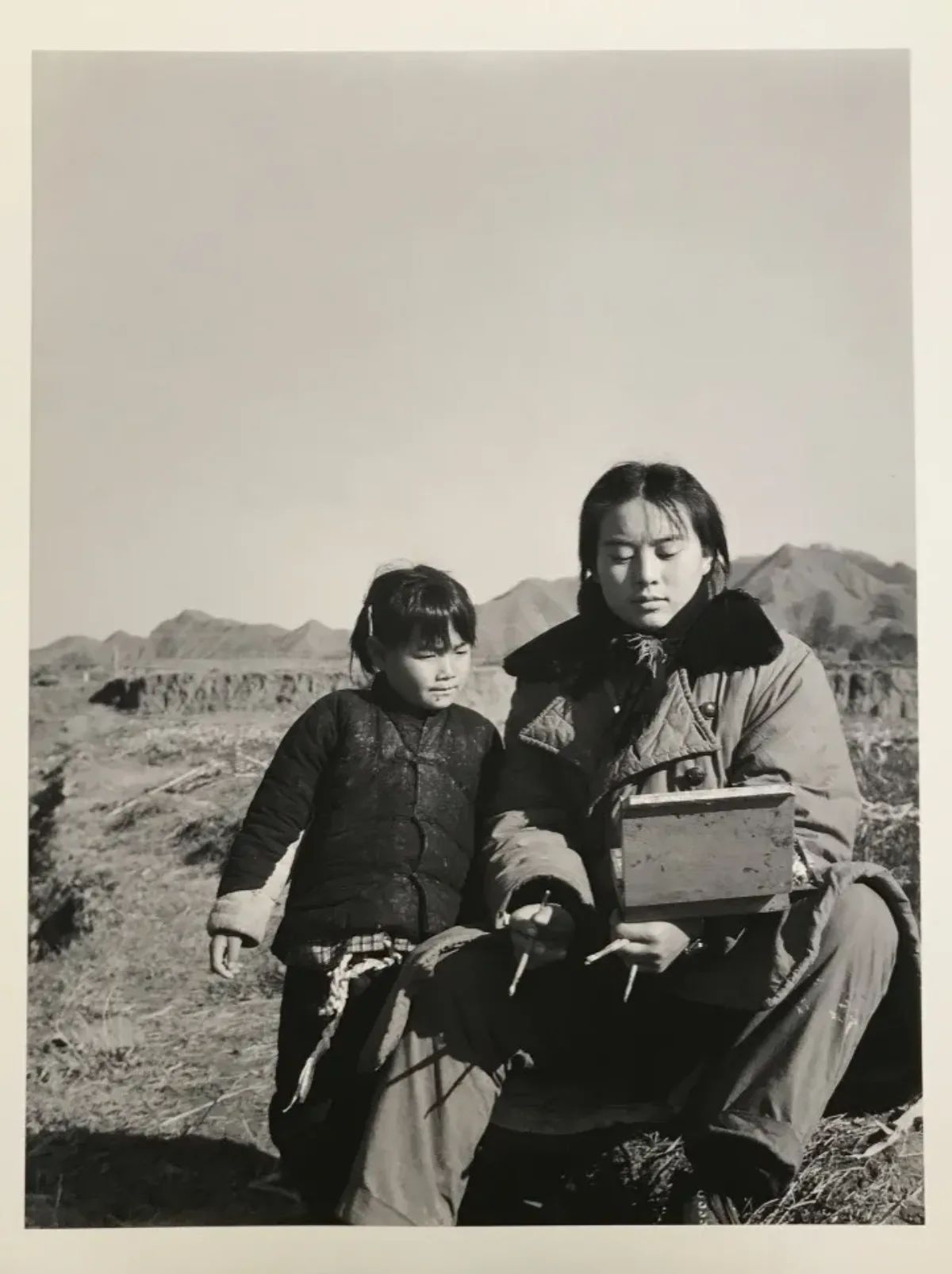

People of the Cultural Revolution

In 1968, Liu was one of ten million urban youths sent to re-education camps in the countryside during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution. She toiled in rice and wheat fields in Dadu Lianghe, a village approximately 50 miles outside of Beijing. She bonded with the other villagers and photographed them using a friend’s Karl Zeiss camera, despite restrictions on the use of the medium by the Chinese government.

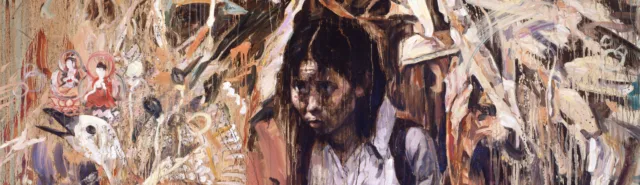

Corn Carrier

Liu’s highly expressive portraits reveal the suffering and perseverance of laborers. As this woman is burdened under the weight of the crops on her back, her face shows anguish and fatigue. Liu’s signature drip marks, which she calls “weeping realism,” further elicit an emotional response from the viewer.

A Closer Look: Bird Imagery

Liu frequently includes birds in her works with various cultural connotations. Cranes were signs of good luck, serenity, and blessings while Mandarin ducks were considered symbols of love and devotion. Images of sparrows allude to Mao Zedong’s infamous 1958 Four Pests Campaign, which aimed to eradicate mosquitoes, flies, rats, and sparrows. One of the first actions of China’s Great Leap Forward, Chairman Mao’s plan for national economic reconstruction, the campaign led to ecological disasters and mass starvation.

A Closer Look: Religious Symbols

Other religious motifs in Liu’s compositions include Bodhisattva figures, lotus blossoms, as well as the recurrent use of circles, which refers to the Zen Buddhist philosophy of wholeness, emptiness, and the cycles of life. Liu incorporates these symbols as a way to accompany, guide, and protect the men, women, and children in her works.

Village Photographs

Use the left and right arrow keys to navigate through the slides.

Women at Work

Liu examined photographs of 19th-century China by Scottish and English photographers John Thomson (1837 to 1921) and William Saunders (1832 to 1892), such as this one of a woman working on a loom. The artist was struck by the woman’s concentration on her task, refusing to return the gaze of the voyeur/photographer.

Symbols and Motifs

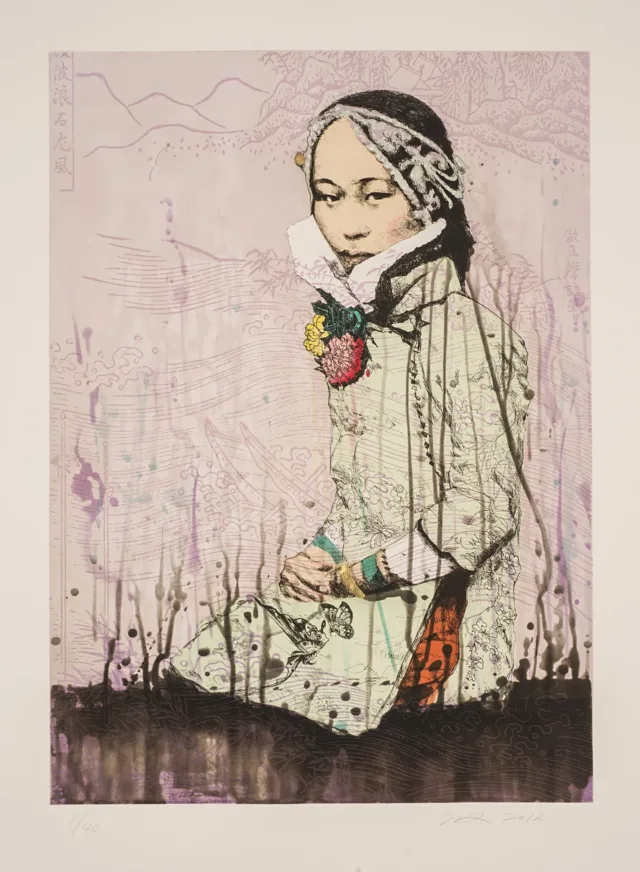

La Ran—Butterfly

Liu created a series of works that allude to La Ran, or Chinese batik, a textile dyeing method practiced in the Guizhou province of southwestern China. The woman seen in profile here has an elaborate coiffure, echoing the form of the butterfly that appears throughout the batik background.

A Closer Look: Snuff Bottle

Liu affixed a snuff bottle to this mixed-media work. Snuff, or pulverized tobacco, was imported to China from the West in the 16th and 17th centuries. Elite members of the Qing dynasty would carry around decorated pocket-sized glass bottles, which continued to be valued collectors’ items over the following centuries.

A Closer Look: Mudmen

Liu includes two sculptures of mudmen, glazed figures of wise men and more rarely, women. Individually molded, they were often portrayed reading, fishing, or holding flutes or other objects of spiritual significance. The history of these figurines in China dates back to the Tang Dynasty (618 to 907 AD). By the 19th century, mudmen remained popular in the Chinese export market; Liu purchased these in the United States.

Winter with Cynical Fish

Winter with Cynical Fish is part of a series of four diptych paintings by Liu, each representing one of the four seasons. The artist painted leaves of white bamboo, a plant noted for its ability to withstand harsh winters, over the woman’s body. Because of its hollow stalks, which yield but are difficult to break, bamboo symbolizes strength, tolerance, and integrity. These attributes made bamboo a common motif for scholar-artists in Chinese painting.

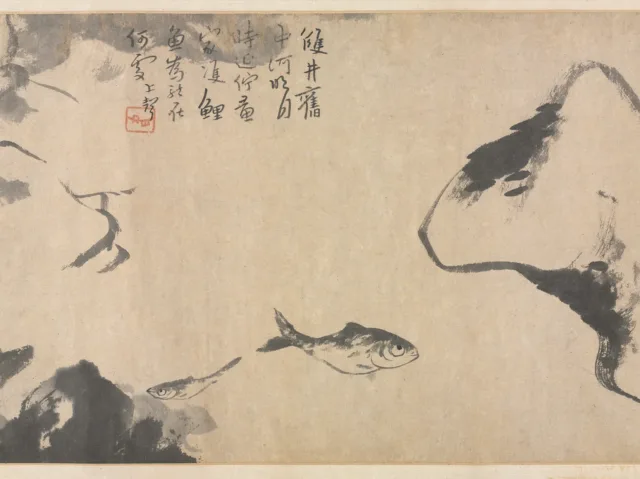

Cynical Fish

The fish imagery came directly from the paintings of the eminent Chinese artist Bada Shanren (born Zhu Da, ca. 1625 to 1705). Bada is known for his satirical images of birds and fish, which reflected moods or temperaments such as sadness, anger, or as Liu noted here, cynicism.

Scholar’s Rock

Liu includes an illustration of a scholar’s rock, a small, ornamental, naturally formed stone placed in imperial gardens and scholars’ studios for meditation or inspiration.

Special Thanks

This online resource was developed in collaboration with Dorothy Moss and the Hung Liu Estate.

Exhibition Sponsors

Hung Liu: Making History is organized by the National Museum of Women in the Arts and generously supported by Stephanie Sale and the members of NMWA.