Audio Files

Curator’s Introduction

Audio Guide 201#

Hi, this is Katie Wat, chief curator here at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Welcome to the exhibition Sonya Clark: Tatter, Bristle, and Mend. This is the artist’s first survey exhibition, a look at her entire career. So you’ll see in full the wide array of materials with which she works—ranging from hair, thread, and pocket combs to all kinds of intriguing found objects. Clark is trained as a textile artist, and she uses those techniques to transform everyday materials and create signs and symbols of social inequities and the inspiring legacy of her ancestors. She was born right here in Washington, D.C., and her works have been a part of our museum’s collection for several years. I hope you’ll enjoy learning more about Sonya Clark.

Sonya Clark discusses Blued

Audio Guide 202#

Sonya Clark, Blued. This piece was inspired by carved wooden African headrests made for married couples. It’s an older work, and in fact I started the work just around the time that my husband and I decided that we wanted to be married. Often those African headrests would have a linkage between them—a chain—that would stand in for unity and connection. Here, the chain can also stand in for that shared history and heritage of coming from people who were once free, and then enslaved, and then had the resilience to become free again and again and again, and fighting against any sort of un-freedom. The title comes from the color blue, as in the blues and the musical tradition, and the word “glued” as in coming together.

Sonya Clark discusses Mom’s Wisdom or Cotton Candy

Audio Guide 203#

Sonya Clark, Mom’s Wisdom or Cotton Candy. This piece is an homage to my most recent ancestor, my mother, Lilleth Ruby (McHardy) Clark, who passed away

in 2018. She routinely saved her hair for me, and I would separate the dark strands from the white to preserve her wisdom. Much in the way that the Yoruba people say that when one’s hair turns white, it’s an example that your soul has become truly wise. My maternal grandmother, my mother’s mother, also had this beautiful white afro, and I long for one myself, but clearly I haven’t earned that wisdom yet. And the reference to cotton candy, both that of the sugarcane fields of our homeland, Jamaica, and the sweetness of her wisdom that was sometimes pleading as she aged. Now this piece might seem like a personal piece, but I also believe the personal is universal. Yes, it’s an image of my mother’s hair, but it’s also this sense that not only was her hair a repository of her DNA, but all people are tangled up in the roots of our DNA. Hair—its texture and type—separates us, but it also connects us. Go back far enough, and all your relatives are in that tangle, too. Let’s be wise about that and see each other’s humanity.

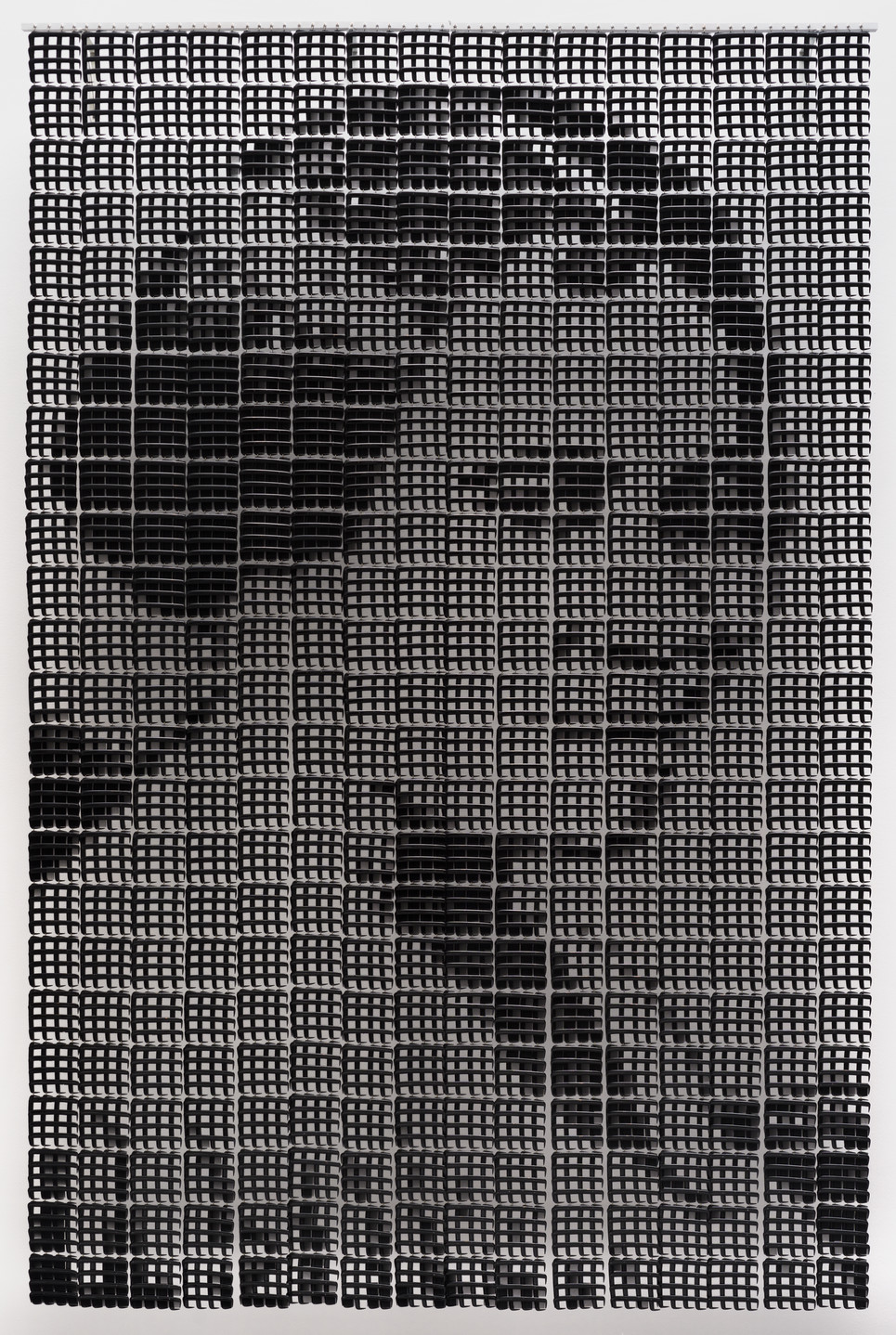

Sonya Clark discusses Madam C. J. Walker

Audio Guide 204#

Sonya Clark, Madam C. J. Walker. I made this as an homage to one of the first self-made women millionaires in this nation. Often, you’ll hear people say she was one of the first Black women millionaires. But while that’s true, it’s also true that she was one of the first women millionaires. She came from the cotton fields of the South and made her own business—became an entrepreneur, a chemical engineer of sorts—in the business of hair care. She navigated a man’s world. I like to think that these fine-tooth combs that I’ve made her portraits of are gendered in that way. And even though they are stamped with the word “unbreakable,” even though they are intended for straight-haired men, she broke those teeth, and she appears. She broke all sorts of barriers, and she appeared.

Sonya Clark discusses Hair Craft Project Hairstyles (Jamilah)

Audio Guide 205#

Sonya Clark, The Hair Craft Project. Imagine having 11 or 12 amazing artists turn you into an artwork. That’s what happened with The Hair Craft Project. For years, I have been thinking about this phrase that my friend Bill Gaskins had said—that hairdressing is a primordial textile art form. So I wanted to make this connection between textiles and hairdressing. I do that a lot in my work, but I wanted to extend that to the people who are working with hair all the time. These amazing women worked their magic on my scalp. And so you see them, their faces there, in the left-hand side of each of these photographs, as a signature of their identity. Do you see the artists there? And then the back of my head, the evidence of their artistry. It was my great honor to be both their art and their walking gallery. Everywhere that I went, I would carry their cards and celebrate their artistry, celebrate this skill that has been how long held in the African diaspora and in African American culture.

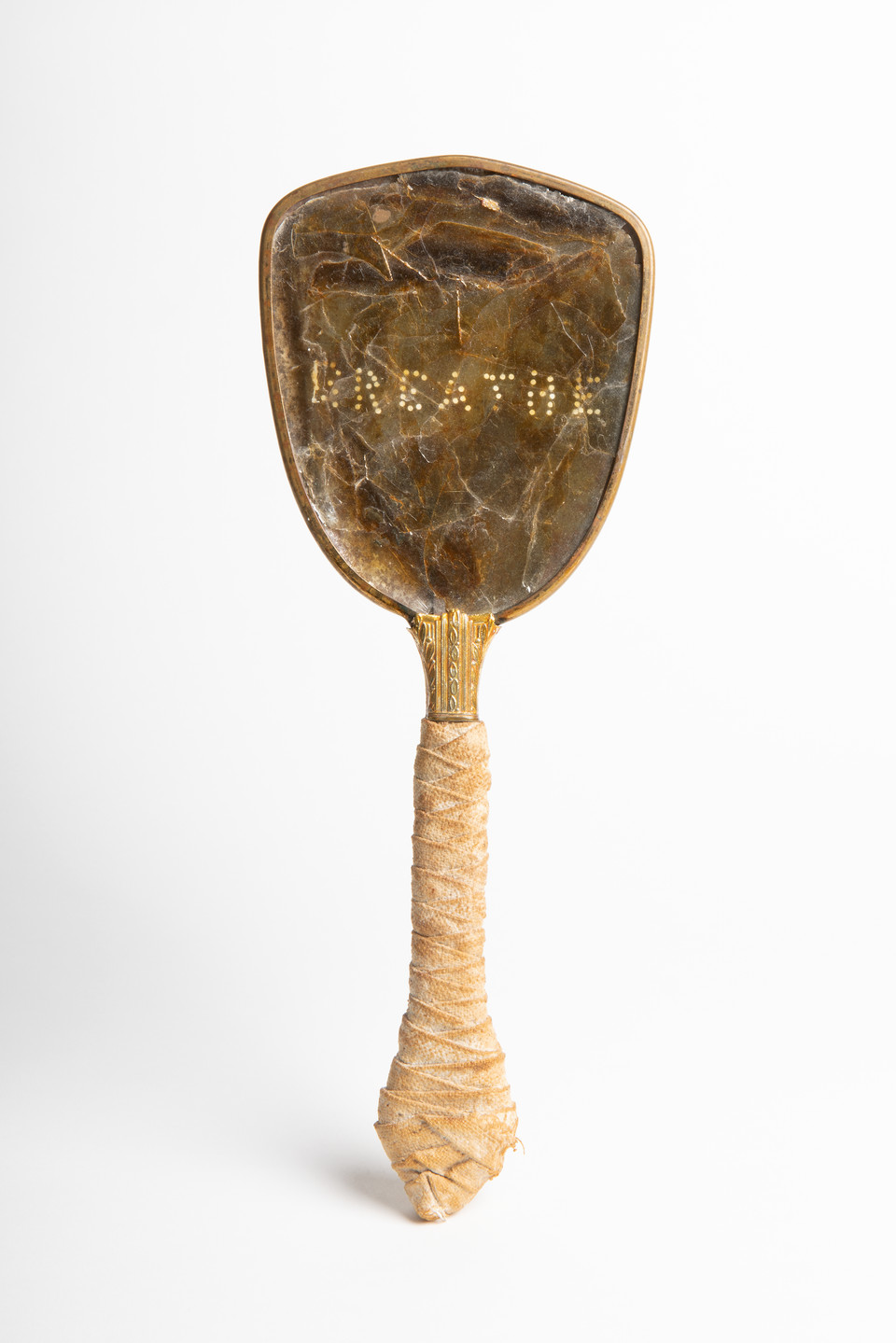

Sonya Clark discusses BREATHE

Audio Guide 206#

Sonya Clark, BREATHE. BREATHE is from 1994. It’s one of the oldest pieces that is in this survey exhibition. It’s a handheld mirror. The original mirror has been replaced with mica, the substance used for the oldest, most ancient mirrors that were found in ancient Egypt—5,000, 6,000 years ago. The handle has been wrapped as if it’s like a mummy. This piece is about life. This piece is about death. This piece is about representation. Can we see ourselves in this mica surface? Do we see ourselves clearly? Do we see our humanity clearly? When we hold this mirror up to the light, its title appears: BREATHE. When a mirror is held under the nose of someone, you can tell whether they’re breathing or not. When we see the word “breathe,” right now, we are reminded of those lives that have been taken through the injustices of this nation. And yet, we continue to breathe.

Sonya Clark discusses Hairbows for “Sounding the Ancestors”

Audio Guide 207#

Sonya Clark, Hairbows for “Sounding the Ancestors.” Do you have a beloved ancestor that you knew in your lifetime, but whose voice you can no longer recall? Maybe it was a grandmother or a great-grandmother, but a great-great-great-great-grandmother or grandfather? Now that’s a voice you may never have heard. It was probably never recorded, and you would never know it. I started wondering, “What would those voices sound like?” And so I turned to my own DNA—my hair, which is of course my DNA, but also a repository for all the DNA and all the ancestors who have come before me. Entangled in that DNA, my ancestors are your ancestors as well. So when this bow is played, we hear the sound of our ancestors.

Sonya Clark discusses Writer Type (Pen and Sword)

Audio Guide 208#

Sonya Clark, Writer Type. You can see that the very title of this piece is a twist on words. And in fact, if this typewriter typed, its font would be a font that I developed based on my curl pattern, called Twist. This piece is about the voices that are heard and the voices that are not heard, the stories that remain untold but are in fact foundational to the narrative of this nation. This typewriter is about giving voice to the voiceless. This typewriter is about using the pen as a sword. And ironically, Remington themselves as a company was known for making guns. They supplied guns to the Civil War, and then also started making typewriters—as in the business of pen and sword.

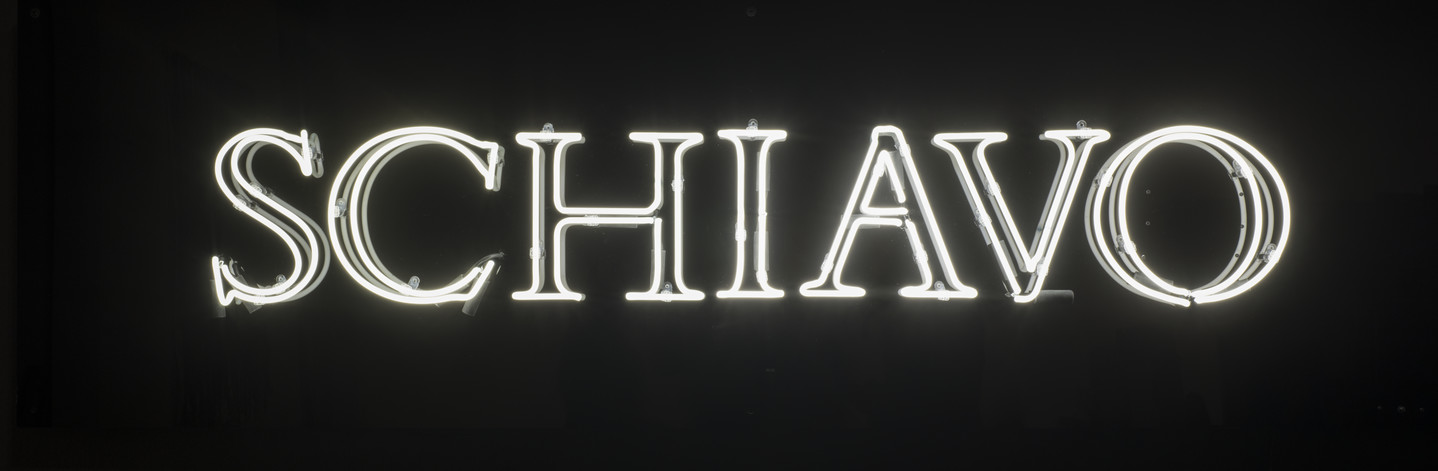

Sonya Clark discusses Schiavo/Ciao

Audio Guide 209#

Sonya Clark, Schiavo/Ciao. It’s a funny thing, words. What you’re standing before is a neon sign flashing the word “SCHIAVO,” which might not be a word that you’re familiar with unless you speak Italian. But you’re probably more familiar with the word “ciao,” a little cosmopolitan way of saying “hello” and “goodbye.” “Ciao” comes directly from the word “schiavo.” You can see that visually here. The word literally comes out of “SCHIAVO.” They have roots together; one might even say they are from the same tree. “Schiavo” means slave, and when we are saying “ciao” to one another, we’re saying, “I am your slave. I am yours.” And in this way, we think about those deep roots of empires, and how systems and cultures built empires, and on whose back. So while many people look to the Roman Empire and think, “This is one of the seats and the foundations of Western civilization,” we think, “It’s also one of the seats and the foundations of slavery.” And that’s what the United States of America modeled itself after—how to enslave others for the benefit of the empire. Ciao to that. Goodbye to that.

Sonya Clark discusses Afro Abe II

Audio Guide 210#

Sonya Clark, Afro Abe. With this piece, I wanted to collapse 1860s and the 1960s, to think about what it meant for the great emancipator to meet the Black liberators. And Afro Abe was born. I also made the very first version of this piece before Barack Obama was elected, as a kind of hair-as-prayer. If we were truly emancipated, then certainly this nation could be ready, many years later, to elect its first Black president. And we did. And so I made 43 more, 44 in all, to celebrate our 44th president and his connections to our 16th president. We know that Abraham Lincoln made an economic decision, as well as, one might argue, of course, a moral decision, when he was freeing people who had been subjugated and made unfree. But I’ll tell you this—these five-dollar bills, these Afro Abes, they’re much more valuable with those afros. Not a one of them has sold for five dollars.

Sonya Clark discusses Gold Coast Journey

Audio Guide 211#

Sonya Clark, Gold Coast Journey. Now I grew up in Washington, D.C., in a neighborhood that was referred to as the Gold Coast, not so much because the people in the neighborhood were extraordinarily wealthy, but because it was mainly made up of Black people who were professionals, who, like my father, had attended Howard University. Gold Coast is also the name that colonizers gave the west coast of Africa in a country that is now known as Ghana. They named it after the commodity that they were extracting from that part of the continent. Also being extracted from that part of the continent were human beings, who were slave trafficked and brought across the Atlantic to places like huge enslavement ports like Richmond, Virginia. That journey is about 5,242 miles. The length of the 18-karat, hair-thin gold wrapped around this African ebony spool is scaled miles to inches. It measures 5,242 inches.

Sonya Clark discusses Cotton to Hair

Audio Guide 212#

Sonya Clark, Cotton to Hair from 2009.The materials really matter in this piece. It’s made out of human hair, which happens to be my hair, the artist’s hair, an African American woman’s hair. It is both personal and collective. It is my hair, but it stands in for the hair of all people of African descent who have been forcibly migrated or whose ancestors were forcibly migrated to this part of the world. On the other part is cotton, a cotton ball that was plucked directly from a cotton plant. And then the bronze makes up the stem of this cotton plant. Bronze is usually used for big sculptures and monuments. Here, we have a subtle monument to the labor of African Americans, the labor that we provided to this nation, and the labor that we provided globally to increase the economics of nations around the world during the transatlantic slave trade route. This is a monument to our labor. This is an acknowledgment of our humanity.

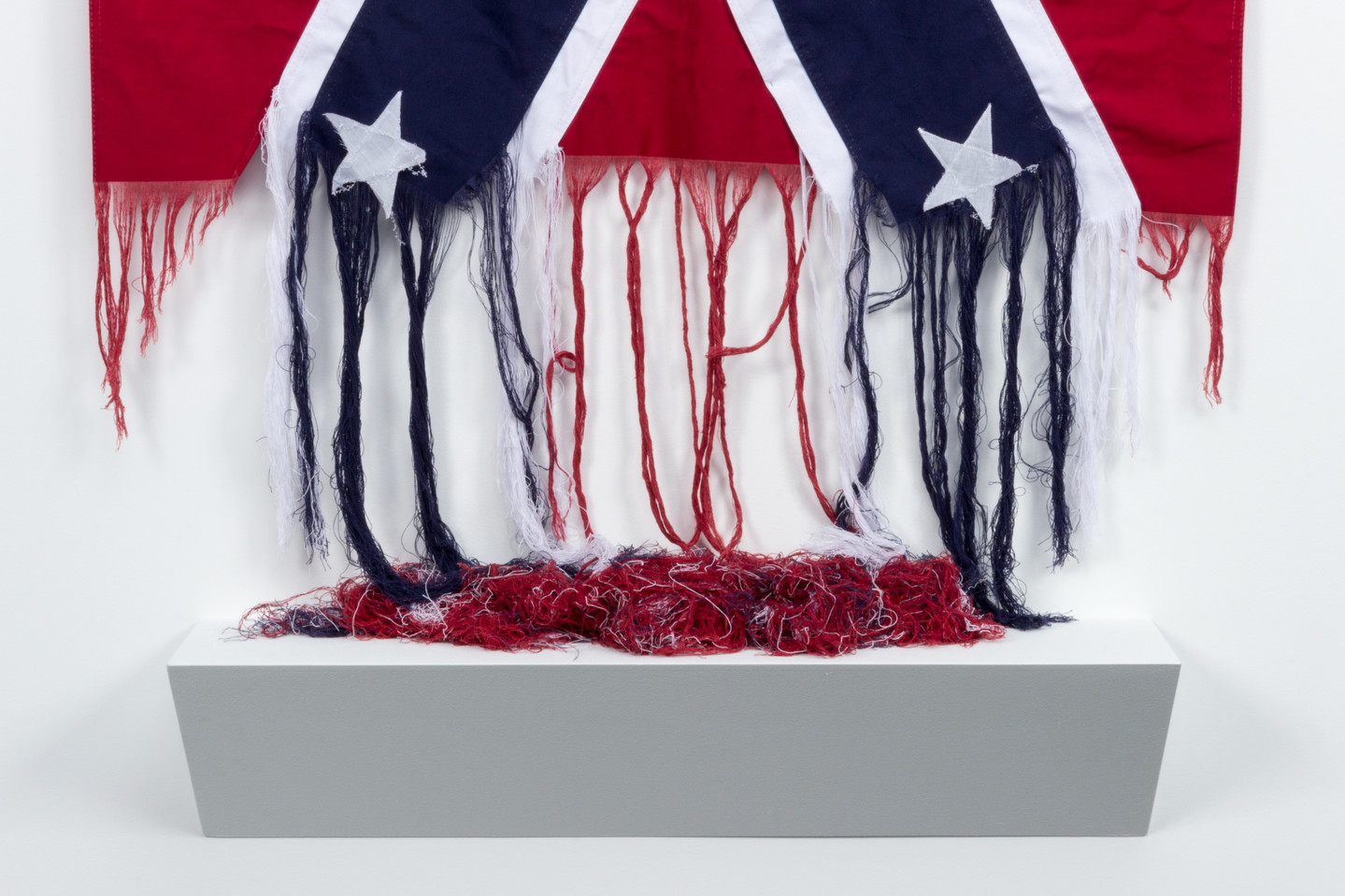

Sonya Clark discusses Monumental Cloth (Sutured)

Audio Guide 213#

Sonya Clark, Monumental Cloth (Sutured). It’s troubling, but it’s true. Most of us are painfully familiar with the Confederate battle flag. And most of us are painfully unfamiliar with the Confederate truce flag. The flag that was used to surrender at Appomattox. I myself just encountered it about a decade ago. By chance, I was walking through the American history museum at the Smithsonian, and next to Lincoln’s top hat I saw this humble, half of a dish cloth, yellowed with age, with three little red stripes. And the label read “Confederate truce flag [laughs] used at Appomattox.” And I thought to myself, “why…wait, wait, what is this? How come I don’t know this?” And then I decided that I needed to reproduce it, that this needed to be a monument. That we need to remind white supremacists [laughs] that they surrendered, that the war is over, and it’s time for the reconciliation and the reparations to take hold.

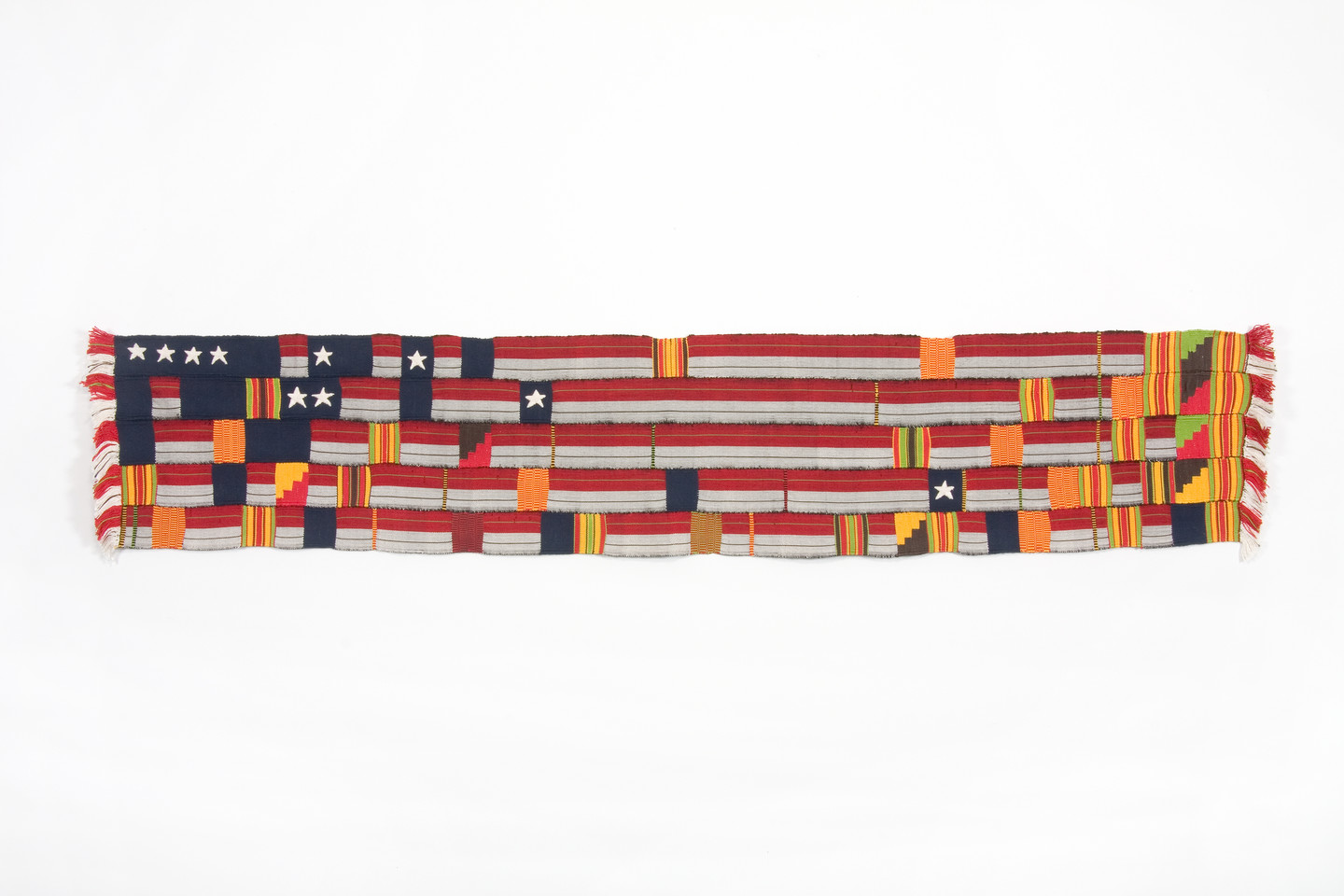

Sonya Clark discusses Gele Kente Flag

Audio Guide 214#

Sonya Clark, Gele Kente Flag. I wanted to make a piece about how textiles speak. You can hear in the word “textile” is the word “text.” That’s because the two words share a common etymology in the Greek texere, which means “to weave.” This textile is intended to speak about the way that we are named and the way that we name ourselves. Often when the word “American” is used, it refers to European Americans, and this piece I wanted to honor African Americans. So I brought together two cloths that have to do with Africanness and Americanness. Kente cloth, which is a strip-woven cloth with these beautiful insets of color. These beautiful insets of color are also stand-ins for proverbs and have deep and rich stories in and of themselves. And of course you can see the American flag is embedded there as well. The word “gele” not only refers to a cloth, but refers to a way that a cloth is worn—specifically, a head tie that you would find among the Yoruba people in Nigeria. When I made this piece I happened to be in conversation with the great painter Sam Gilliam, and he said to me, “Others look to a monument. We look to a piece of cloth.” He was referring to his own use of freeing canvas from stretcher bars and allowing his paintings to drape. And I’ve been holding onto that thought all these many years and made many pieces, including some of the pieces that you will see in this exhibition, that are referred to as monumental cloths. In fact I believe cloth can be monumental, and I’m grateful to Mr. Gilliam for providing that language and that framework to think of cloth in that manner.

Sonya Clark discusses Unraveling

Audio Guide 215#

Sonya Clark, Unraveling. The thing about cloth is that we’re touching it all the time. It touches us; it holds us. There’re barely any times in the day when you’re not touching cloth, and yet, most people don’t understand how cloth is made. And this is the metaphor. Unraveling is a performative piece. I would ask people to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with me as we would pair together and with our hands, we would undo, thread by thread, this symbol of hate: the Confederate battle flag, popularly known as the Confederate flag, though there are many. This is just the one that became most popular, most well-known, because of the Ku Klux Klan. We would stand together, and people would come to understand how this cloth was made in the unmaking of it. They would also understand what slow work it is to actually undo it—but necessary work, satisfying work, work that must be done.