Born in 1948, a year before the Chinese Communist Party came to power, Hung Liu grew up in an environment that discouraged apolitical personal expression. Although she received training in socialist realism, Liu delighted in painting landscapes and drawing portraits based on photos, both unsanctioned forms of expression under the Maoist regime. It was only when Liu immigrated to America that she began to experiment with art’s potential beyond the realm of realistic representation.

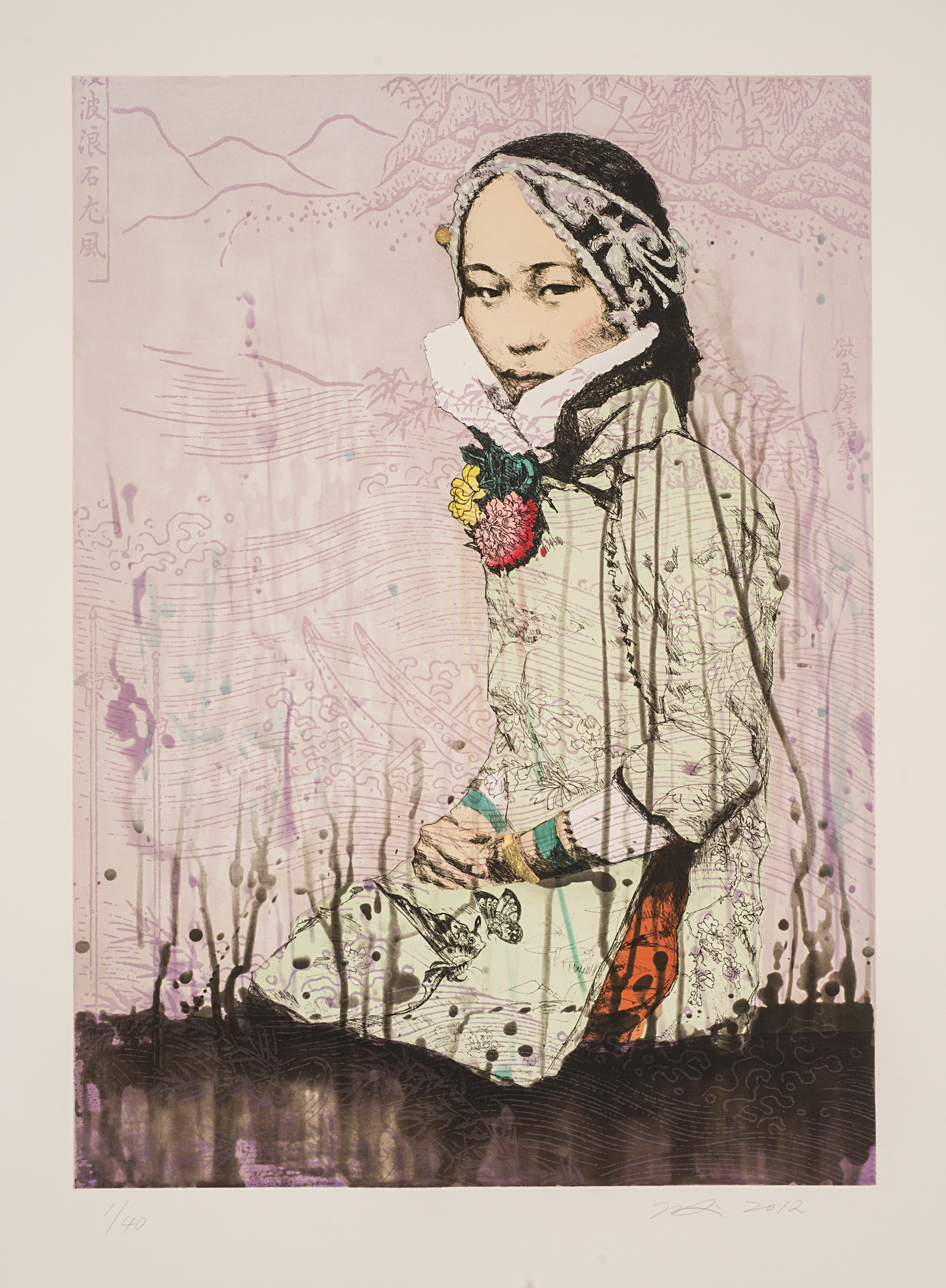

Liu’s best-known works are paintings based on historical photographs. Re-creating the images in an enlarged format, she transforms humble documents into large, vivid portraits. Perhaps in rebellion against her training, Liu rejects the rigid realism of Chinese art of the post-Mao era. Instead, she embraces traditional conventions of Chinese painting that value energetic, expressive line work. She uses a restorative process in her work, layering bright colors over the black-and-white original images as well as decorative textures and whimsical forms from classical paintings. She often drips linseed oil over the canvas to create a hazy veil that hints at the muddled refractions of history and memory. By focusing on her subjects, Liu dignifies and humanizes these nameless faces of history. In lieu of capturing their precise historical context, she enhances the mysterious aura lent to them by the passage of time.

Liu imbues unlikely subjects with an awesome presence, as seen in her works on view at NMWA. On a 1991 trip to China, Liu discovered a collection of old photographs depicting unnamed prostitutes. In Shan-Mountain (2012) and Shui-Water (2012) she extracts these women from their source photos and presents them, magnified in scope, in dramatic portraits. Her focus on restoring their integrity as people over restoring the images as historical artifacts indicates a deep engagement with the humanity of her subjects. Once again, her vivid palette not only brings them to life, but endows the women with an air of nobility that suggests they might be royal concubines or even empresses.

The names of the paintings themselves allude to the Chinese name for landscape paintings (shan shui hua, literally “mountain river paintings”) where towering mountains and sweeping rivers dwarf the occupants of the land. Although she imitates the aesthetics of landscape painting, Liu ultimately subverts their focus. Rather than emphasizing nature’s grandeur, she asserts the dignity of these individuals. By blending Western portraiture with Chinese landscape painting, Liu casts her subjects as monumental figures that stand independent of time or place. History may pick and choose who to remember, the paintings seem to say, but the integrity of the human spirit will thrive regardless.