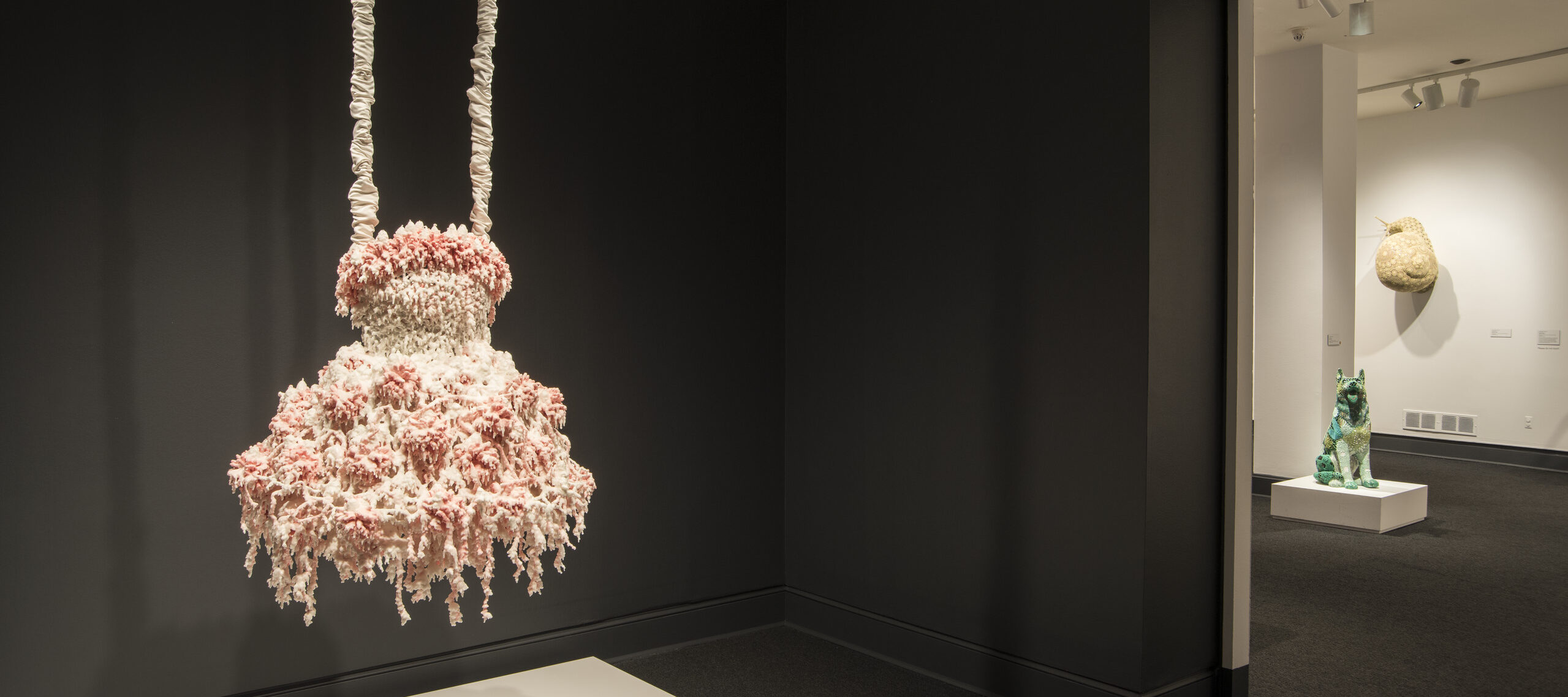

Disturbingly alluring, Petah Coyne’s Untitled #781 certainly packs a visual punch. The wax-work evokes a plethora of associations, both pleasant and disconcerting. Viewers may be surprised to learn, however, that Victorian novels and vanitas still-life paintings are among Coyne’s artistic references.

Upon closer observation, visitors can detect references to still-life painting in Coyne’s work. While “still-life” can refer to widely varied arrangements of inanimate objects, 17th-century Dutch still-lifes particularly appealed to Coyne—the genre was tremendously popular at that time, incorporating elaborate displays of wealth and excess. As masterful representations of the rich textures of exotic imports, still lifes epitomized sensory delight and prosperity. Images of Venetian glass, Chinese porcelain, and exotic flora often crowded these canvases.

Coyne’s contemporary work, although a different medium, similarly overwhelms the senses. Extravagant and festive, Untitled #781 is part of a series of sculptures resembling frosted confections, ornate chandeliers, and frilly dresses. Like still-life, it embodies the Victorian adage “Nothing succeeds like excess.”

The grandeur of Coyne’s sculpture is not its only quality reminiscent of still-life painting. Both also incorporate spiritual symbolism. Religious iconography was forbidden in the Dutch Reformed Protestant Church, prompting artists to disguise religious symbols in their paintings. (Fish commonly symbolized Christ and butterflies represented resurrection.) Coyne’s use of dripping candle-wax references her Catholic upbringing and time spent in votive-lit churches. Her sculpture’s resemblance to a lace-drenched wedding dress may also allude to religious accoutrements of marriage.

Raw with white accretions and mossy appendages, the sculpture has a striking quality of decay. Coyne’s work symbolizes the transience of life. In a similar vein, vanitas still-lifes referenced human mortality through depictions of skulls, clocks, and melting candles in addition to wilting flowers and half-peeled fruits.

Captivated with the concept of deterioration over time, Coyne has stated, “I love Charles Dickens’s Miss Havisham, who was left at the altar. Time stopped for her… She lived in that bridal dress, withered like grave clothing.” Coyne is “not interested in the fresh, new bride…I’m much more interested in being past your prime.” The artist refers to her own bride-like waxworks as “the parties afterward, the residue that’s left.” It’s not about what’s fresh and new: there’s beauty in the excess, too.

Petah Coyne explores the tensions between lushness and decay, beauty and decadence, and life and death. When you look at Untitled #781, what other images come to mind?