Women played a vital role in shaping the visual culture of the Low Countries, present-day Belgium and the Netherlands, during the 17th and early 18th centuries. Women Artists from Antwerp to Amsterdam, 1600–1750 is the first-ever survey exhibition of women artists from this region and time period. Including more than 40 artists, with many works on view in the United States for the first time, it demonstrates that women were an active and consequential part of one of the most robust and dynamic artistic economies of the era.

Powering the Art Market

Women were crucial to the artistic economy of the Low Countries, and their labor was a significant factor in the unprecedented expansion of trade and the thriving market for art and luxury goods in this era. In an essay for the exhibition’s catalogue, research assistant Katie Altizer Takata writes, “Women were involved in nearly every aspect of these luxury markets, making some of the most expensive and sought-after objects of the time, including paintings (Rachel Ruysch), paper cuttings (Johanna Koerten), botanical volumes (Maria Sibylla Merian), and lace, as well as more common items such as prints, books, and ceramics.”

Local Networks, Global Reach

Women painters and printmakers catered to the art market just as their male counterparts did, innovating and adapting along the way. Painting for the first open art market in Antwerp, where buyers could procure finished paintings (instead of having them commissioned), Clara Peeters (ca. 1587-after 1636) relied on skill and technique to reproduce her popular imagery quickly. She strategically repeated motifs across works, such as the carp in the center of Still Life of Fish and Cat (after 1620). Collectors would have appreciated the verisimilitude with which Peeters depicted varied textures in her still lifes, a genre in which she was a pioneer.

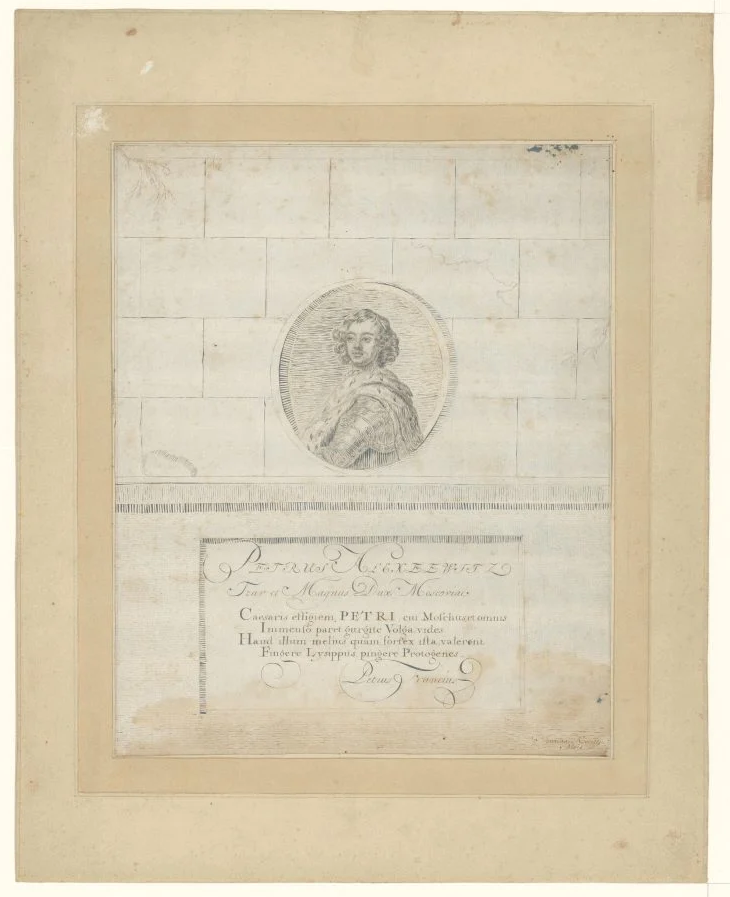

One of the visitors Johanna Koerten (1650-1715) welcomed to view examples of her work was Tsar Peter the Great of Russia, an indication of her international reputation. Koerten created his portrait, as she did with many other illustrious people of the time, including King William III of England. In her portrait of the Russian Tsar, Koerten skillfully uses shading cuts to render different materials, such as his soft ermine stole and rigid armor.

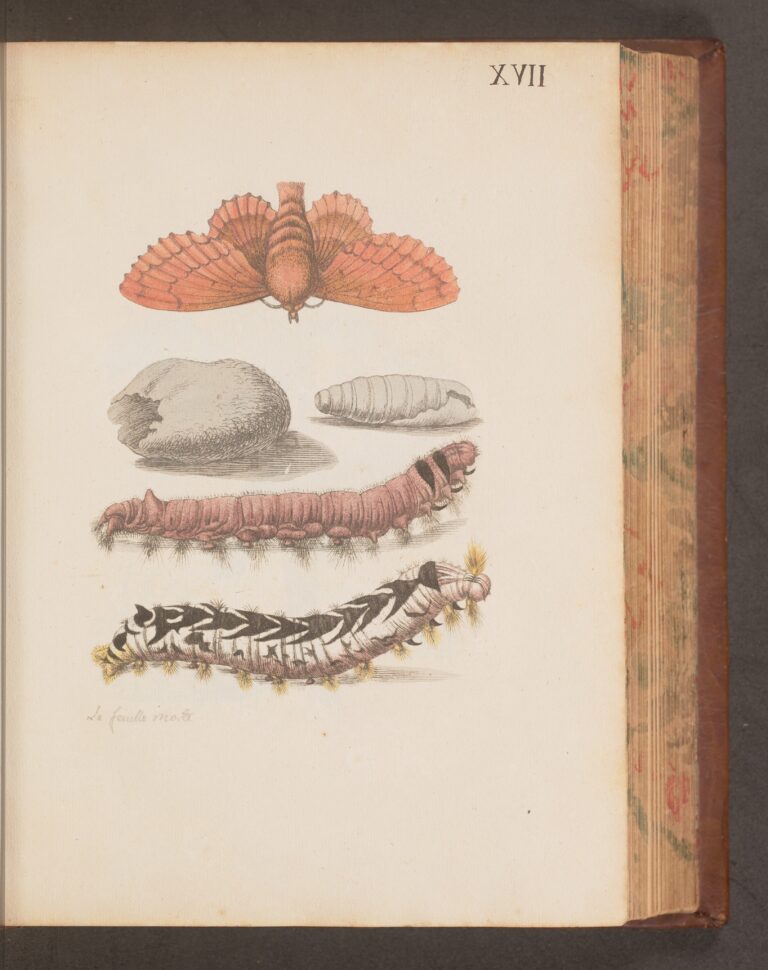

The Dutch edition of a book on the life cycle of caterpillars by Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) indicates the popularity of her scientifically exacting work in the Dutch Republic, her adopted home (the volume was first published in German in 1679 while she was living in Nürberg). Merian’s documentation of the metamorphoses of butterflies and moths, both written and illustrated, were observed from specimens that she raised for study. While living in Amsterdam, Merian was part of a wide network of artists, collectors, and scientists interested in studying the natural world.

The rapidly expanding colonization of the Americas also affected the work of women: There was greater demand for lace, specifically for export to the to the Spanish colonies, where the upper classes were eager to replicate the luxuries of home. Vast quantities of lace were shipped from Flanders (and France), traveling overseas via the port of Cádiz. This example is typical of the style of lace that was produced in Flanders by women specifically for export to Spanish colonies.

Leaving Their Mark

Works in this section demonstrate that women artists were connected to each other and to their wider artistic communities. They made technical and stylistic innovations, and patrons bought their work through the open market as well as through important commissions.

Want to learn more? Visit Women Artists from Antwerp to Amsterdam, 1600-1750, through January 11, 2026, and buy the exhibition catalogue from NMWA’s museum shop.