Drawing inspiration from the social and economic conditions of the Great Depression, American illustrator and printmaker Blanche Grambs incorporated the struggles of the New Deal era into her work. Grambs studied at the Art Students League of New York, a progressive institution where teachers often encouraged students to integrate socially driven messages into their assignments. Guided by her conviction that artists’ work could combat societal ills, Grambs created prints of jobless and homeless people, as well as industrial workers and miners. While she only produced prints for a short period of time in the 1930s, she is best known for these intaglios, lithographs, and relief prints.

NMWA recently acquired four prints executed by Grambs during her time at the Federal Arts Project (FAP), a short-lived New Deal program run under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Two of the works, Coal Breakers, 1937 and Coal Cars, 1936, belong to a series of industrial mining images that Grambs created while visiting the Coal Region of Eastern Pennsylvania. During the summer of 1936, Grambs’ printmaking instructor Harry Sternberg invited her, along with other students, on an excursion to Lansford, Pennsylvania. Appalled by the miners’ working conditions she encountered, Grambs found new socially relevant subject matter to supplant her previous work that had illustrated the dreadful conditions of the Depression in New York City. Grambs’ newly chosen-issue to depict still resonates with audiences today, who witness the perils of mining all too frequently in the news.

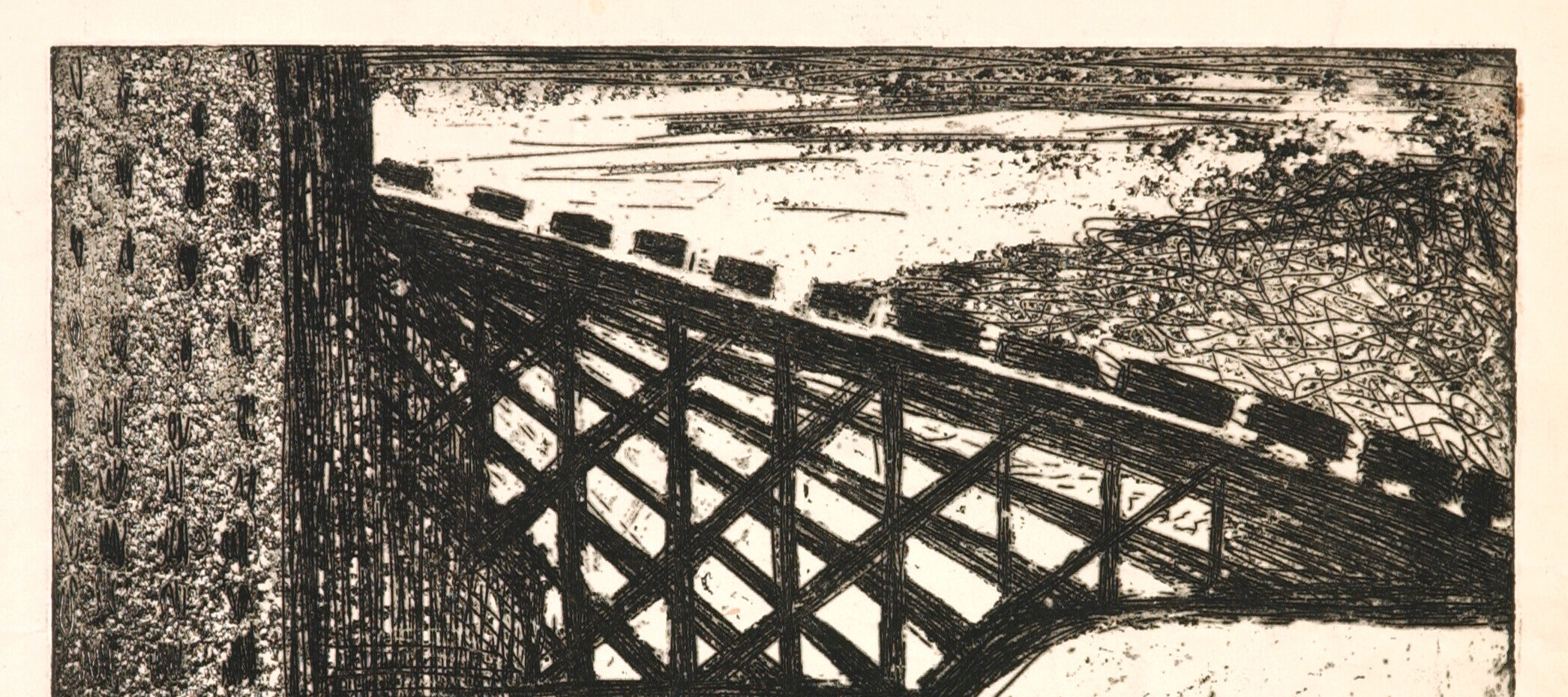

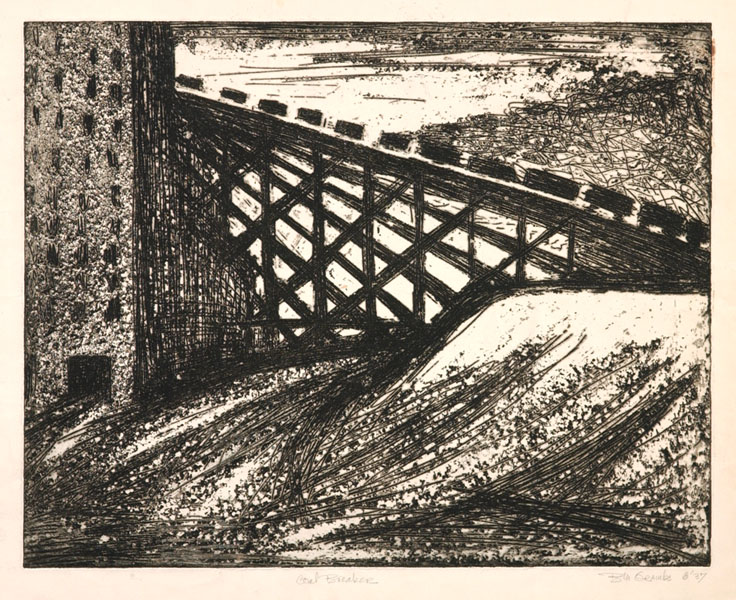

Unlike her contemporaries who glorified the industrial age and the machine, Grambs relayed the miner’s plight to the viewer through several portraits of the miners and depictions of mines. For Grambs, lithography and aquatint provided the ideal medium to capture her experience of the mining industry: interaction with the miners, exploration of the mining towns, and descension into the abysmal mining tunnels. Aquatint, in particular, allowed the artist to emulate the soot-laden atmosphere and diffused light caused by the perpetual smoke from coal-pit fires. In her aquatint Coal Breaker, piles of tailings, the waste by-product of coal production, overshadow the silhouetted train cars that ascend to and depart from the processing plant. The rough, grainy texture of the etched surface and the prominent placement of the mining waste of Coal Breaker sully the popular image of a pristine, streamlined industrial plant.

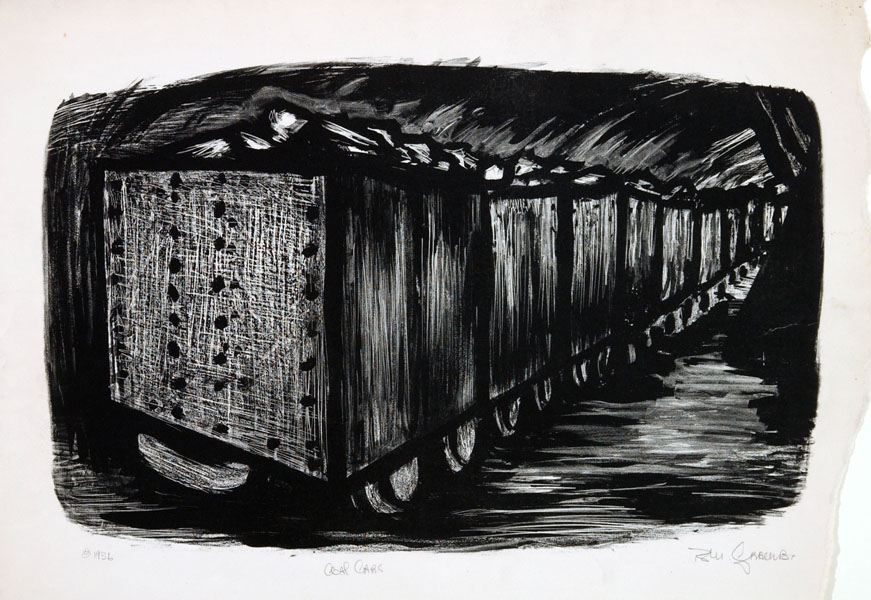

Unlike Coal Breaker’s aboveground perspective, Grambs’ 1936 lithograph titled Coal Cars guides the viewer into the subterranean interior of the mine. The print evokes a stark contrast between the seemingly-endless mining tunnel and the train car brimming with coal nuggets. The underground coal car transporting its lucrative commodity recedes sharply into the distance, perhaps suggesting to the viewer the overwhelming amount of labor involved. The aquatint and lithograph both omit the actual miners from the scenes, but nonetheless, human presence is palpable. While Coal Breaker informs viewers of the mounting waste and deplorable working conditions on the surface, Coal Cars reveals a similar sight underground, reminding the viewer of the daunting task required of mine workers.

Born in Beijing in 1916 to American parents, Grambs was raised in China, but arrived in the United States in March 1934 after receiving a full scholarship to the Art Students League. Though she remained politically active throughout her life, Grambs stopped producing prints with a social agenda when she left the WPA in the 1940s to work as a fashion illustrator for Woman’s Day magazine. She later transitioned to book-illustrating in the late 1950s and 1960s, working well into the 1980s. Nevertheless, it was her printmaking years in the thirties in which her art and her commitment to social change were seamlessly intertwined. Blanch Grambs passed away this past March in her New York residence at the age of 94.