Have you ever been on a camping trip or a hike and caught yourself exclaiming, “That sunset is sublime!” or “Aren’t those mountains picturesque?” In our modern-day language, we use the terms sublime and picturesque loosely to describe sights and sounds that strike us as aesthetically pleasing. This broad usage was not the case, however, for nineteenth-century British artist Richenda Cunningham, whose lithographic print portfolio ”Nine Views Taken on the Continent” is now on view at NMWA through March 13.

Cunningham was greatly influenced by Romanticism, a pervasive movement sweeping England in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that encouraged a love of nature and travel. At the time, Romantic artists used three distinct terms to describe the natural world: the sublime, the beautiful, and the picturesque. The beautiful referred to the peaceful, orderly qualities of nature, a placid pastoral scene or a landscape illuminated by the setting sun. When talking about the sublime, Romantics meant the overwhelming, frightening aspects of nature, such as a crack of lightning or a waterfall, something that could overpower you.

The picturesque, however, was much more elusive in definition. The term was coined in 1768 by British clergyman and travel enthusiast Reverend William Gilpin (1724 to 1804) to describe the beauty of roughness, irregularity, and disrepair in nature and architecture. Picturesque artists saw beauty in unlikely places, a moldy bridge, a ruined gateway, or an ancient arch overgrown with ivy. In addition to presenting broken-down edifices as things of beauty, picturesque artists like Cunningham shared a common technique: embellishment. Cunningham and her ilk manipulated their work to include visually striking elements, a jagged mountain range or a broken fence, to heighten drama and picturesque effect.

Cunningham’s “Nine Views Taken on the Continent,” c. 1830, is a print portfolio depicting ruined buildings and dramatized landscapes in France, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland, locations she likely visited in 1815. Epitomizing the picturesque style, Cunningham’s embellished views served as artistic resources for tourists who wished to employ an imaginative aesthetic lens when traveling. Portfolios like Cunningham’s additionally served the needs of English citizens who, while perhaps unable to afford an expensive sojourn to continental Europe, could expose themselves to views of faraway locations via travel prints.

Can you spot the picturesque embellishments in Cunningham’s prints? Take a minute to compare her views of specific European monuments with photographs of the same locations.

Dominating the city of Heidelberg, Germany, from its location on the Königstuhl hillside, Heidelberg Castle had long been a popular subject for Romantic artists like J. M. W. Turner (1775—1851) who painted the structure often throughout his career. Cunningham embellished her rendering of Heidelberg Castle for picturesque effect: the castle is compressed to appear dramatically tall and placed on a jagged rock formation reminiscent of the Athenian acropolis. Rugged mountains loom in the background, with gnarled trees and twisted bushes framing the scene on either side. In actuality, the castle is composed of many lower-lying structures and flanked by ambling mountains—an overall much tamer scene than Cunningham’s majestic view.

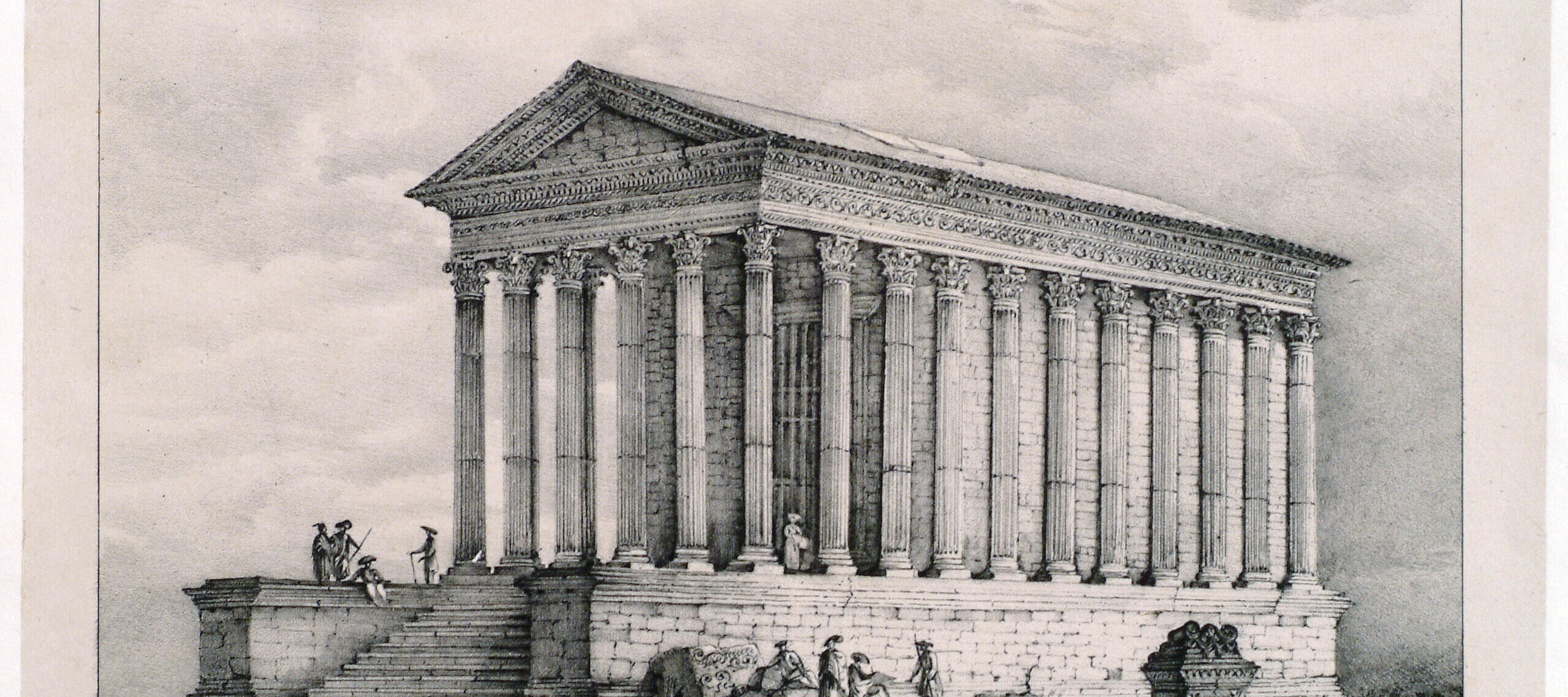

Crossing the Gard River in southern France, the first-century AD Roman aqueduct known as Pont du Gard is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the most popular tourist attractions in France. In use until the Middle Ages, the bridge became a popular destination for Romantic tourists and artists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As with Castle of Heidelberg, the aqueduct in Cunningham’s print is vertically compressed for visual impact. The vantage point is low, with viewers poised to gaze upward at the aqueduct, lending a sense of awe and wonderment to the structure. A craggy outcropping dominates the left side of the print, while wild, overgrown vines sprawl across the arches of the aqueduct.

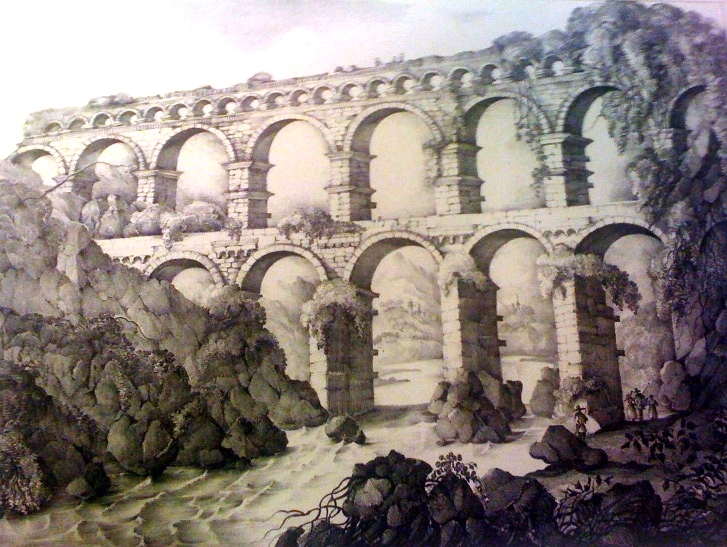

Near the present-day city of St. Rémy de Provence in southern France lay the ruins of Glanum, a Roman-era settlement and one of the most important archaeological sites in the country. Several monumental structures were built in Glanum during the reign of Augustus (27 BC—14 AD), including two monuments collectively known today as “Les Antiques”: a triumphal arch with reliefs depicting Julius Caesar’s conquest of Gaul, and a tall cenotaph, or funeral monument, dedicated to the Julii clan. These two monuments have captivated the imaginations of tourists and artists for centuries.

Cunningham employed ample artistic license in her rendering of the triumphal arch by adding a full-scale mountain range to the background (stylistically similar to the unusual, jagged mountains in Castle of Heidelberg), adorning the foreground with ruined column capitals, and incorporating minuscule human figures at the center to overstate the arch’s scale. Most notably, Cunningham eliminated the cenotaph from her view altogether in order to place full emphasis on the imposing form of the arch.