The fourth installment of NMWA’s biennial exhibition series, Organic Matters—Women to Watch 2015 is presented by the museum and participating national and international outreach committees. The exhibition’s artists redefine the relationship between women, art, and nature. Associate Curator Virginia Treanor spoke with emerging and contemporary women artists featured in Organic Matters.

Organic Matters—Women to Watch 2015

Artist: Dawn Holder

Nominating committee: Arkansas Committee / Consulting curator: Courtney Taylor, Arts & Science Center for Southeast Arkansas

1. Organic Matters includes art that refers or responds to the natural world. How do you think your work, Monoculture, relates to the theme of nature?

I find the intersection of nature and culture to be fertile ground for artistic exploration. I am particularly interested in the way we cultivate, manicure, rearrange, and exploit the natural world.

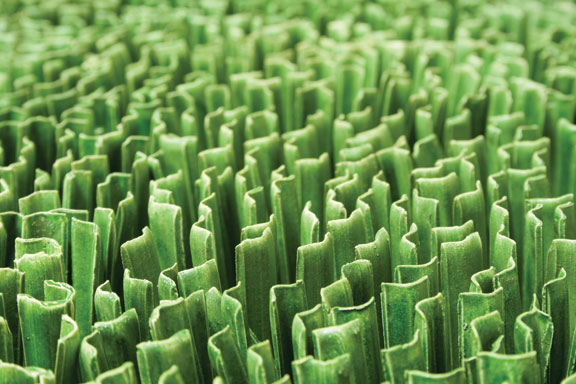

The lawn, which I explore in Monoculture, is of particular interest to me because of its multivalent nature. It is a “natural space” in that it is comprised of plants and landforms, yet the lawn is a wholly artificial construct, a highly controlled space requiring labor, chemicals, and specialized equipment to maintain.

I am fascinated by suburban America’s desire to construct this hybrid artificial-natural landscape and what it signifies in terms of time and resources. I think the lawn is our culture’s fantasy version of the natural world.

2. Is this work representative of your oeuvre? How does Monoculture fit into your larger body of work?

For almost a decade, my work has explored the idea of landscape and domestic space through installation and sculpture. Aesthetically, my recent installations, such as Monoculture, have been influenced by the way Minimalist sculptures occupy space. Yet rather than being simplified, my work is highly detailed and engages surface as much as form. I align my practice to the repetitive and decorative craft tasks historically relegated to women, such as needlework. I think of my current studio explorations as combining horror vacui surface with minimal form, a Maximalist Minimalist approach. So far, Monoculture is definitely the most labor-intensive installation that I have created . . . . But the visual reward is worth it and I don’t see this aspect of my work changing.

3. As an artist, what is your most essential tool? Why?

My mind is my most essential tool, along with my hands, a bag of plaster, and maybe some random pointy objects . . . I could get by with a shish kabob skewer and old paring knife if I had to. Since my forms and materials change so much from project to project, the ability to brainstorm and solve problems has become an integral part of my creative process. Also, having the ability to push onward when mind and body are ready to give in becomes really important when making thousands of the same form. This perseverance pays off when I see all of the pieces massed together.

4. Who or what are your sources of inspiration and/or influence?

I read every day—books, essays, and articles about current events, social issues, the environment, pop culture, and art/craft theory. One idea I have been incredibly interested in lately is the necropastoral, a term explored at length by poet and critic Joyelle McSweeney. She states that the necropastoral is “a political-aesthetic zone in which the fact of mankind’s depredations cannot be separated from an experience of ‘nature’ which is poisoned, mutated, aberrant, spectacular, full of ill effects and affects.” Something about the forcefulness with which this idea recognizes and combines the devastating powers of the Anthropocene and the sublime forces of the wilderness strikes a chord with me.

5. What’s the last exhibition you saw that you had a strong reaction to?

I was recently in New York and had the chance to see Samara Golden’s The Flat Side of the Knife at PS1. This two-story installation depicts interconnected multiple levels which are variations of a domestic space, sparsely furnished with beds, plants, musical instruments, and other objects made from reflective insulation board. Mirrors and upside-down placement of objects further serve to confound the viewer, as do a number of misdirected staircases. I was enchanted by the way Golden’s installation plays with perception and dimensionality. The contrast of the aged, brick walls of the gallery space and Golden’s use of surface and material works to create an impossible, unreal, yet familiar space. The private nature of the setting also added to the unsettling and voyeuristic quality of the piece. I am attracted to work that creates an alternate space that I can project myself into, or even better, that I can momentarily lose myself in.