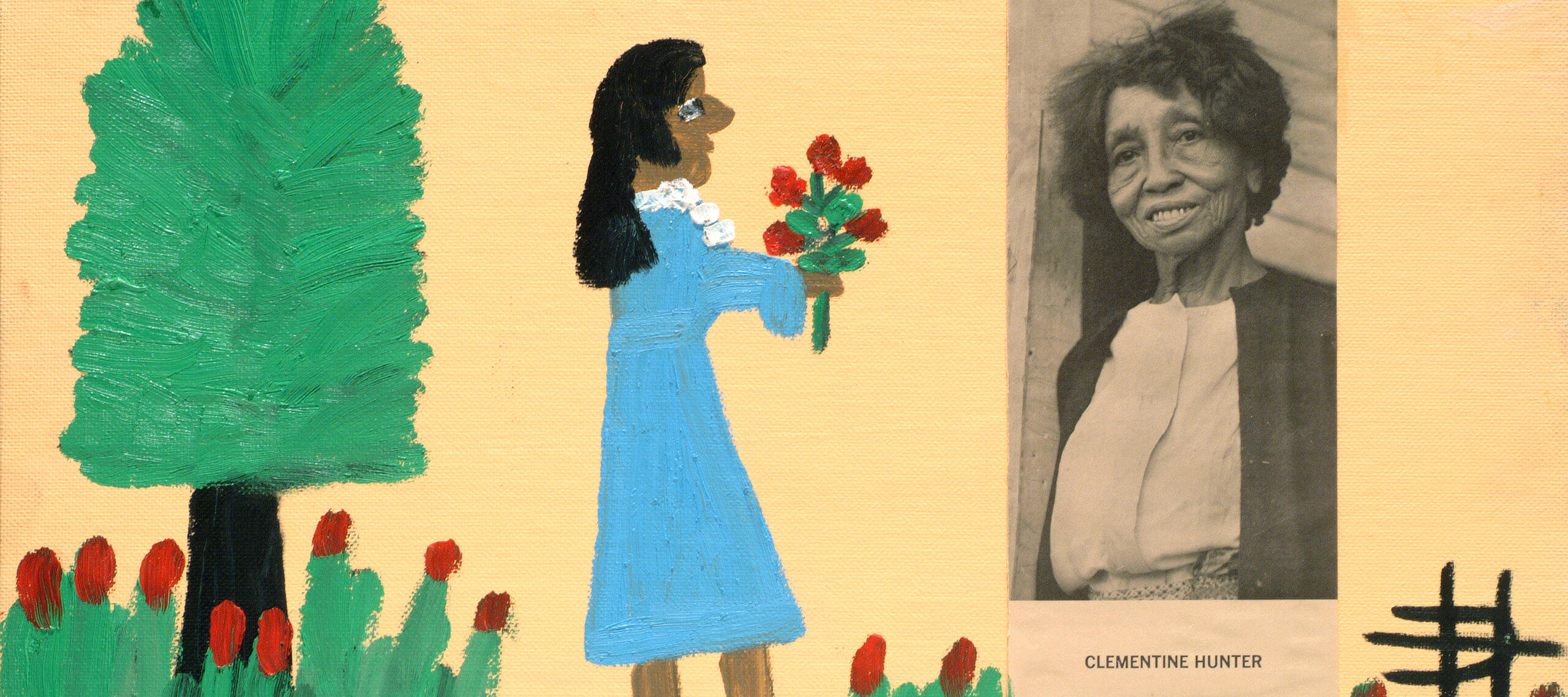

Impress your friends with five fast facts about African American folk artist Clementine Hunter (1886 or 1887 to 1998), whose colorful works are in NMWA’s collection. Self-taught, Hunter began “marking pictures” in 1939, when she was in her 50s. Her work depicts everyday moments and special occasions in the Cane River region of northern Louisiana, where she lived her entire life. Despite her late start, Hunter created thousands of works and is considered one of Louisiana’s most well-known artists.

1. Home, Haven, Historical Site

Hunter lived and worked at Melrose Plantation, built by and for free Black people, for 75 years. When Melrose became a haven for artists and writers, Hunter gained access to the materials and encouragement needed to begin painting. Today, Melrose (and its African House murals by Hunter), is one of 12 sites in the Historic Artists’ Homes & Studios network that celebrates the contributions of American women artists.

2. Unconventional Creations

Hunter painted on a variety of surfaces, including boards, window shades, and jugs. While her work recalls artistic traditions across time and place (narratives on ancient Chinese scrolls and Greek pottery, hierarchical scale in Egyptian and Renaissance works, and repurposed found objects in modern art) they sprang independently from Hunter’s imagination.

3. May I Have Your Signature, Please?

At the prudent recommendation, and steady hand of, an early supporter, Hunter’s name first appeared on her works in the mid-1940s. Her signature evolved over time, culminating in the stylized symbol of a backward “C” overlapping an “H.” Historically, unsigned art, especially by women artists, has been vulnerable to misattribution.

4. Controlling Her Narrative

Recognizing the growing interest in her work, Hunter took charge of her image and success. She mounted pay-to-see exhibitions at her home, charged visitors to take pictures with her, sold her work (for modest prices), and even created the occasional self-portrait.

5. Faux Folk

Hunter forgeries have circulated since the 1970s. In 2009, the FBI finally cracked the case, putting an end to decades of deception. Dead giveaway? The forger added dirt to “age” his knockoffs, but the soil wasn’t from Melrose. Considered the first FBI case of its kind, it legitimized folk art and protected Hunter’s legacy.