Maggie Foskett (American, b. 1919) would not have you call her a “nature artist;” nor is she a romantic about humanity’s relationship with the natural world. Rather, she is an artist who creates images that suggest, as she says, “How delicate our balance with mortality is.”

Ms. Foskett was born and grew up in Brazil. Vacations were horseback rides through the country and great care had to be taken that “you didn’t step on the wrong things.” This was the root of her keen observations of the cast-off bits of nature, its debris and refuse. She walks through the woods and picks up small, organic objects that simply aren’t meant to last and brings them back to her darkroom.

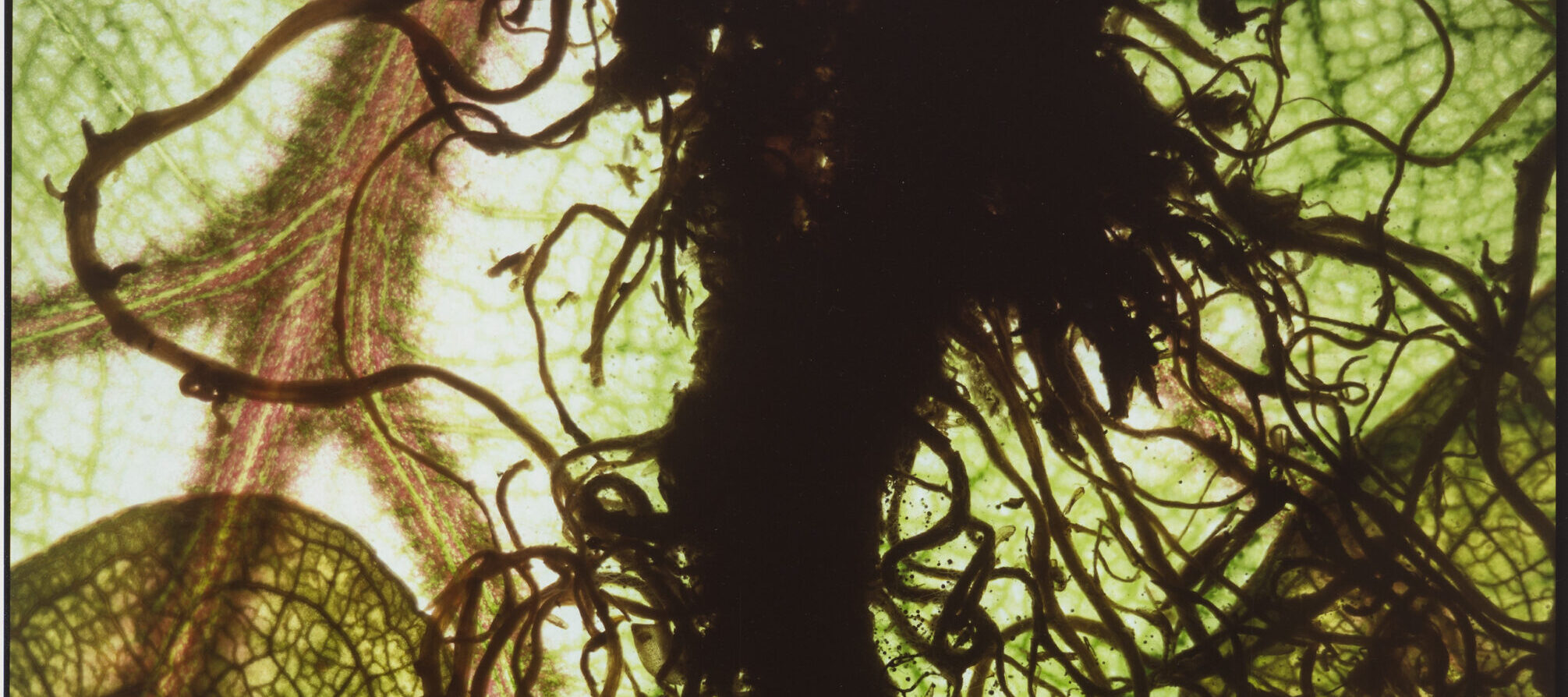

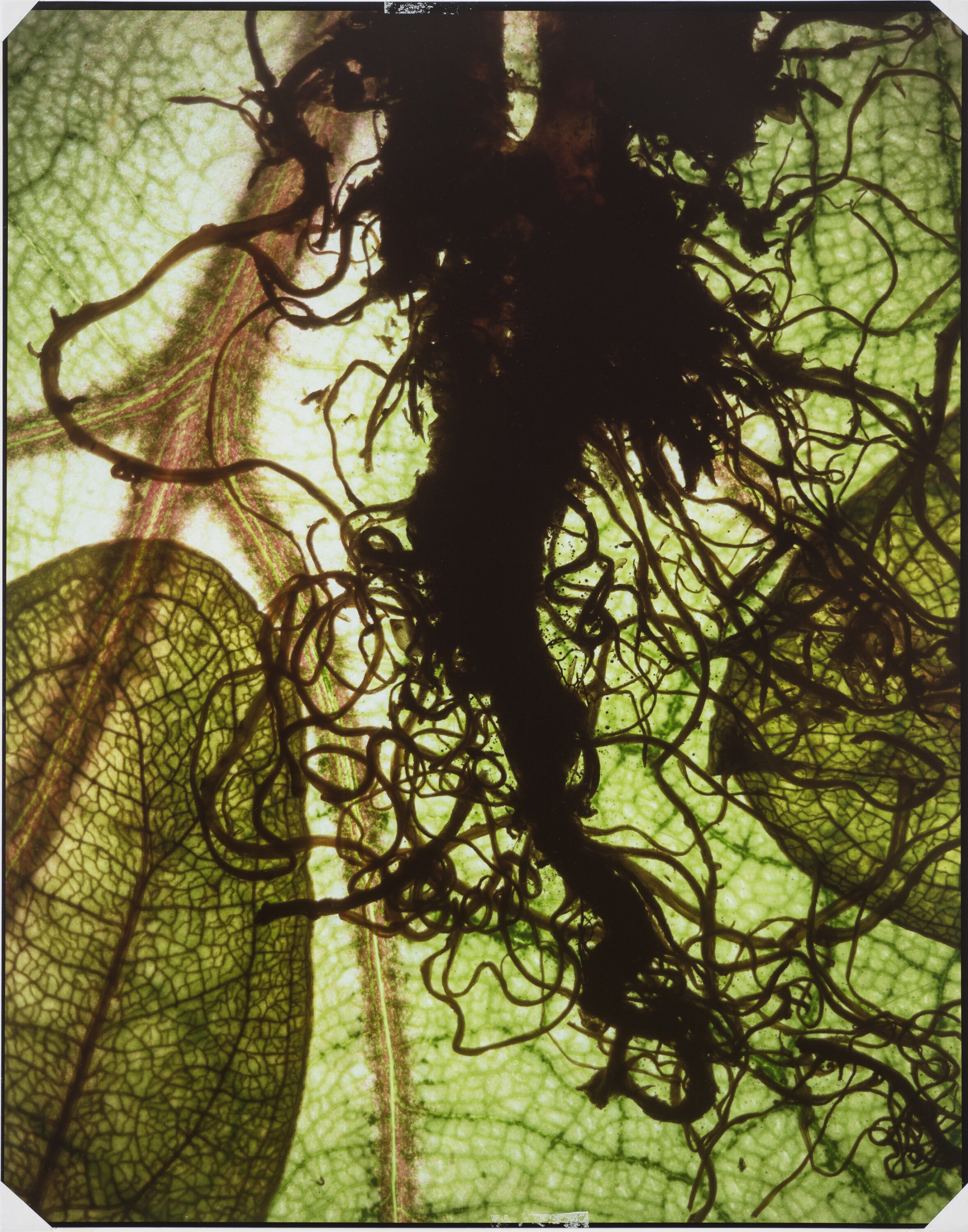

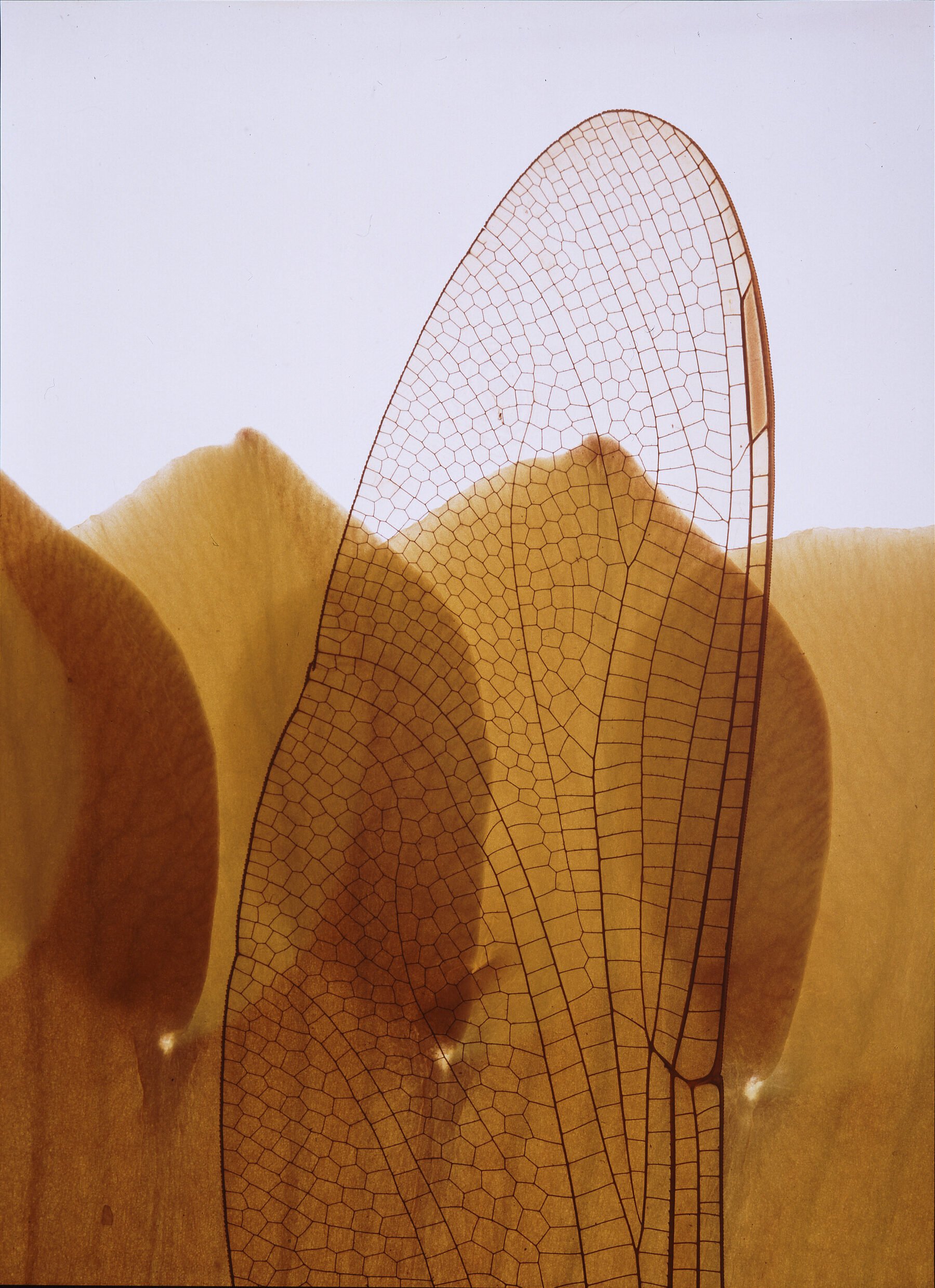

Once she has the materials for a particular composition together, she layers them between glass plates to create her own negative—no need for cameras or film. The technique is a variation of cliché verre, which traditionally uses drawings made on glass projected onto photographic paper, usually a gum bichromate print. “Cliché verre is not a photograph,” she says. “I can usually get three prints from each composition before the materials fall apart.” She places the “negative” in a photographic enlarger to project it onto light-sensitive paper to create the prints. It is vital that light be allowed to pass through the materials.

One might think that this would put some serious limitations on the materials suitable for creating the images, but Ms. Foskett has no lack of ideas. Leaves, snake skin, even onion slices are fair game. “I made an entire series with onions, but I have no sense of smell…the darkroom with all the onions and chemistry was very interesting at that time!” One of her favorite materials is the x-ray image; she collects x-rays and even uses her own. “Animals have always fascinated humans. When the x-ray came along, it gave people the opportunity to see inside animals like they never had before. I love bones because they tell a story—in a way they’re almost eternal.”

Science is a great inspiration for Ms. Foskett. Advancements in technology such as DNA sequencing and space exploration all lend to her view of modern science as being turned inward in a reflection of human existence. She sees the natural world not in the context of being conventionally “beautiful,” but as an “arena of survival” in which mortality and the relationship of pattern echo one another.

Ms. Foskett has been working in the darkroom for many years; she has worked alongside many artists, not just photographers, in Maine where she spends her summers. When I was looking through her resume I noted that she had worked with Ansel Adams, so I couldn’t resist asking about that experience. “They always start with him!” she said. “He was a wonderful teacher, and a very kind man. Students would come up and ask him, “What camera should I use?” He would look at them very directly, and then point to his eye and forehead, saying: “The camera is up here.”

I asked Maggie what her advice to young aspiring artists would be. She thought for a minute and said: “Use your hands – anything tactile. Touch, volume, and texture are very important. Mix anything, use any materials. And make sure you pick darkroom materials they won’t discontinue!”

Six of Maggie’s cliché verre images will be on view in Telling Secrets: Codes, Captions and Conundrums in Contemporary Art—a perfect fit, as she has always been “attracted to the ambiguity of nature.”