Judy Chicago (née Judy Cohen) was born on July 20, 1939, in Chicago, Illinois, into a household that supported her creative and intellectual interests. In her autobiography, Through the Flower, Chicago describes her mother as a woman of culture who worked and entertained friends with intellectual conversation. Because of her mother’s influence, Chicago has said that she grew up with the mindset that she could do whatever she wanted, yet this proved to be quite challenging as she began to realize the unequal dynamics of the artistic culture of the time. During her years as an undergraduate and graduate student in the University of California, Los Angeles, Chicago attempted to assimilate into the artistic clique and sought the approval of her male peers.

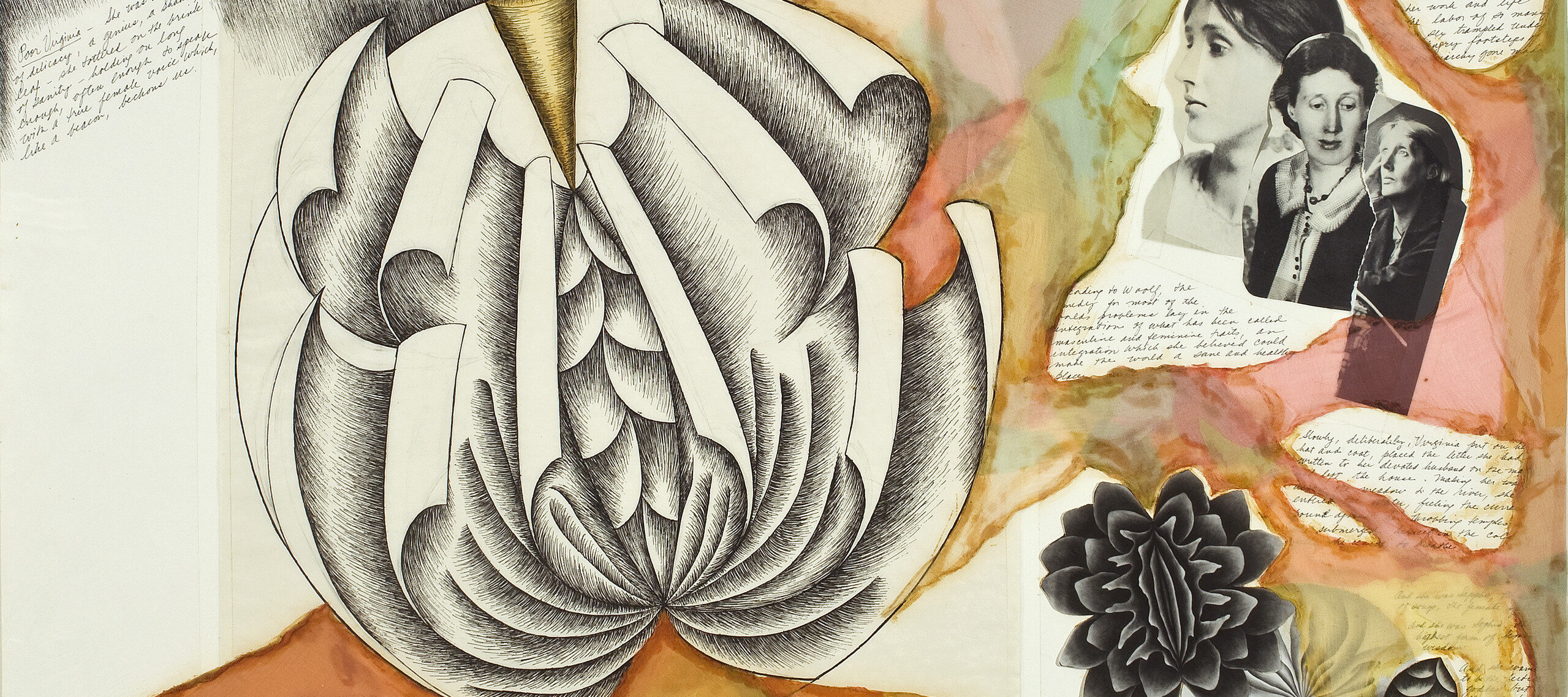

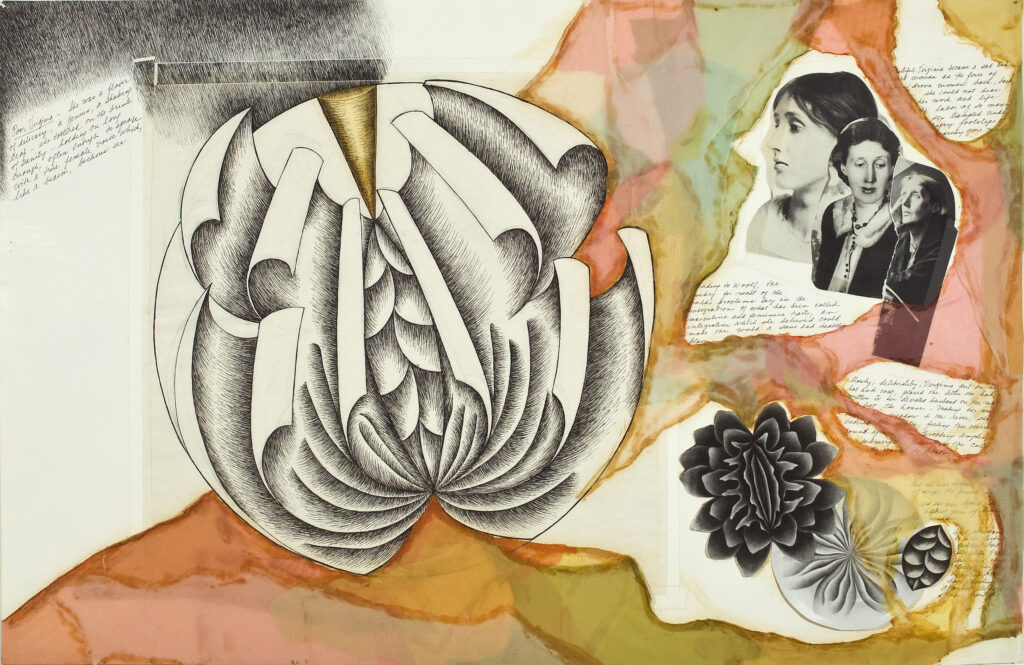

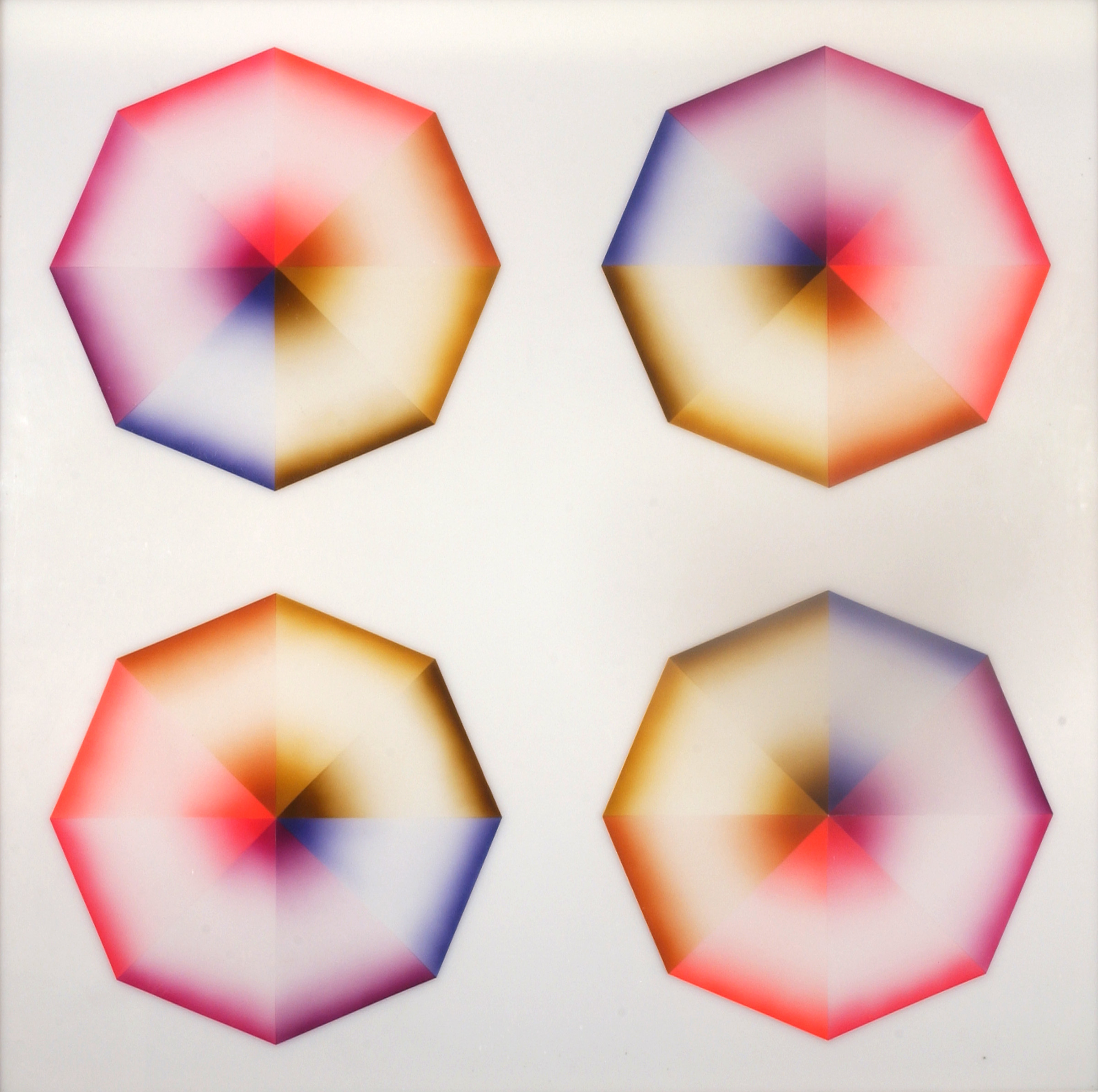

After graduating, she attended auto-body school, in keeping with the trend for many aspiring male artists of the day. She has described this voyage as going into the “male world” where she thought the “real” art was. Due to her male teachers’ critiques and her male peers’ skepticism about her as an artist, Chicago found herself conflicted between her feminine sensibility and her inhibitions about projecting that feeling in her art. Though she used techniques popularized by predominantly male participants of the Los Angeles-based Look movement, she aimed to produce art that depicted her experiences as a woman. Of course, this did not come without struggle, yet upon returning back to painting, she developed “central core” imagery, which iconographically expressed what it meant to be a woman. She was also able to incorporate and appropriate some of the stereotypically “male” techniques she had learned, such as auto-body painting. Soon, feminist themes in her artworks would solidify to become the doctrines of her personal and artistic philosophy.

While the ’60s were a time of both internal and external struggle for Chicago, the decade catalyzed her artistic development in the ’70s. In 1972, Chicago, along with her California Institute of the Arts colleague Miriam Schapiro, worked with a group of female students to create the site-specific installation Womanhouse. This collaborative project probed the roles of women and the limitations society placed on them, attracting nationwide attention. In 1974, Chicago began work on her best-known piece, The Dinner Party, a symbolic history of the great women of Western civilization, in which she prepared a triangular dining table with a unique table setting for each of her 39 women subjects. Since then, she has continued as a pioneer of feminist art and has helped further the progress of women artists.

In honor of Chicago’s 75th birthday, Judy Chicago: Circa ’75 will feature 13 artworks that are characteristic of her work from this period, spurring and responding to the second-wave feminist movement. The exhibition, including preparatory drawings and test plates that the artist made for The Dinner Party, will be on view at NMWA through April 13.