Mexican artist Graciela Iturbide is considered one of the most important and influential Latin American photographers of the past four decades. Her oeuvre is rich in dramatic and intense imagery that portrays the surreal and spiritual aspects of daily life. Iturbide’s works reveal her compassion for and dedication to her country and its people. We are fortunate to have two of her works in the exhibition Eye Wonder: Photography from the Bank of America Collection as well as one work in NMWA’s collection.

Born in 1942 in Mexico City to a wealthy, conservative Catholic family, Graciela Iturbide was the eldest of 13 children. Despite her ambitions to be a writer, family and societal pressure persuaded her to marry at the age of 20 and have three children.

In 1969, she decided to enroll at the Centro de Estudios Cinematográficos at the Universidad Nacional Autónama de México to become a film director. When she took a class with master photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo, she began concentrating her interests on photography. Bravo was greatly impressed with Iturbide’s talent and invited her to be his assistant. She worked closely with Bravo from 1970 to 1971 and was deeply influenced by his poetic style, however, Iturbide wanted to focus her efforts on what she described as “photo essays” as opposed to individual photographs as works of art.

Iturbide traveled to Europe where she met internationally renowned photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, whose notion of the “decisive moment” (the creative moment when the photographer decides to capture a photograph) greatly influenced her work. She returned to Mexico where she spent the 1970s working for the Instituto Nacional Indigenista documenting indigenous cultures throughout the country.

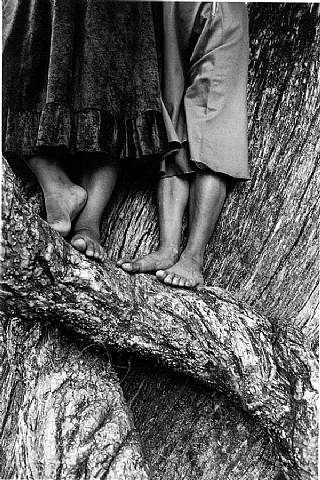

In 1979, at the invitation of the painter Francisco Toledo, Iturbide began photographing the Zapotec women of Juchitán, documenting this ancient, matriarchal community. For more than a century, the socially and politically independent women of Juchitán, located in the southern state of Oaxaca, Mexico, have been viewed as symbols of national strength. Iturbide photographed the community’s marketplace, scenes of domestic life, as well as rituals and special celebrations.

Iturbide refused to approach her work as an outsider, choosing instead to visit and interact with the communities in which she worked. “I usually get to a town with my camera and I introduce myself as a photographer. I tell the people that I plan to stay for a while. I like it when people know that I am taking their picture. Complicity, for me, is looking at someone and discovering that they are looking back. If I don’t get that answering look, I don’t get results,” said Iturbide.

NMWA NOTE:

In 2007, NMWA presented 12 never-before-seen photographs by Iturbide of Frida Kahlo’s private bathroom at the Casa Azul in the exhibition Frida Kahlo: Public Image, Private Life. A Selection of Photographs and Letters. Kahlo’s private bathroom was sealed until fifty years after her death in 1945. When the room was opened, curators discovered hundreds of articles of clothing, photographs, and decorative objects, as well as her therapeutic corsets, prosthetic leg, and other medical devices. Iturbide’s photographs offer a candid portrait of Kahlo’s hardships and recall the artist’s enduring voice in Mexican art.

Works Cited

Kauffman, Frederick. “Graciela Iturbide”. Aperture, Winter 1995.