Perhaps in reaction to Minimalism, Eva Hesse once remarked, “What makes a tight circle or a tight little square box more of an intellectual statement than something done emotionally, I don’t know.”

While sculptors like Donald Judd and Tony Smith created repetitive and flawless geometric forms, Hesse’s sculptures embraced the imperfect. While Minimalists erased the hand of the artist, Hesse emphasized it through molding synthetic and commercial materials including latex, polymer resin, fiberglass, and rope into organic and individualized forms.

Themes of opposing forces are often at play in Hesse’s work: masculine and feminine, hard and soft, liberation and confinement. While she used materials commonly associated with industrial plants and masculinity, her labor-intensive methods of twisting, winding, and wrapping were traditionally perceived as feminine. This contrast creates a sense of tension, which her sculptures consistently explore.

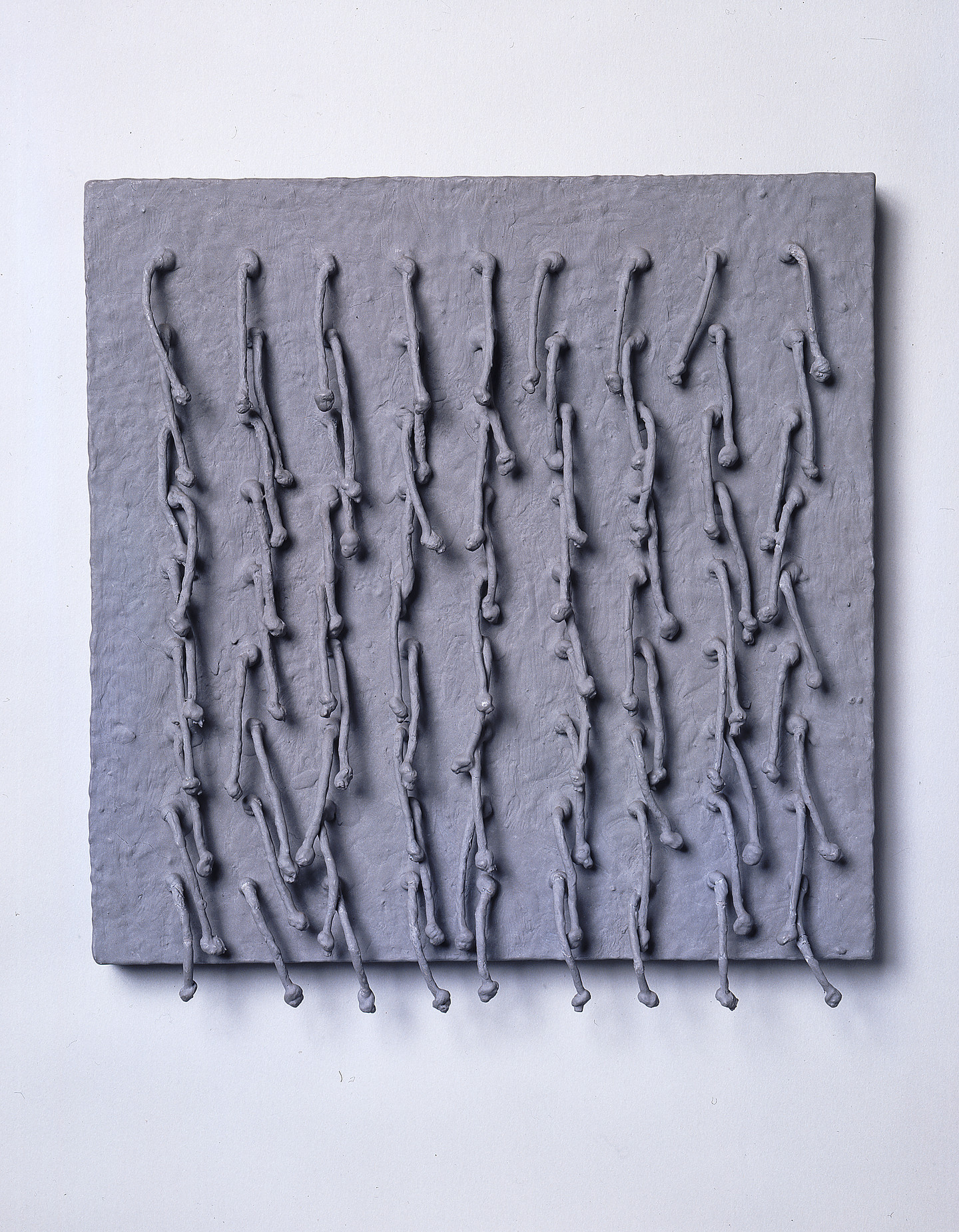

Like many sculptors, Hesse created three-dimensional studies for later works. Though these studies primarily laid the foundation for her final projects, they can also be considered on their own terms. Study for Sculpture, in NMWA’s collection, is one such work. This sculpture typifies Hesse’s style. She used unusual materials including Elmer’s glue, cord, and varnished Masonite to create a nine-by-nine-inch grid of hanging cords. Although the placement of the cords suggests an orderly arrangement of columns, they are spaced slightly unevenly. The limpness of the cords contrasts with the tightly-tied knots on the end of each.

Viewers might sense the weight of those knots, physically pulling down the cords. The hand-worked feeling of the grid’s surface contradicts its dull gray finish, making it more dynamic and less uniform. Overall, Hesse’s sculptures are complicated and deeply nuanced. The more time viewers spend with them, looking closely, the more they reveal.

While feminism is often discussed in the context of Hesse’s art, she did not specifically identify as a feminist. However, her experience as a woman influenced her work, which, in turn, cleared a path for other women artists to follow. She inspired countless artists engaging with feminism in the 1960s and ’70s. Her work pushed boundaries by breaking open the mold of Minimalism and instilling it with a deeper psychology and depth. Today she is recognized as one of the most innovative sculptors working in the post-war period.

Come spend some time with Eva Hesse’s Study for Sculpture in Pathmakers: Women in Art, Craft, and Design, Midcentury and Today, on view through February 28, 2016.