The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction, the newest body of work by iconic feminist artist Judy Chicago, continues the artist’s practice of tackling taboo subjects. In these works, she offers a bold reflection on mortality and the destruction of entire species. Visually striking and emotionally charged, the exhibition comprises more than 35 paintings on black glass and porcelain, as well as two large-scale bronze reliefs. On view September 19, 2019 to January 20, 2020.

When Judy Chicago (b. 1939) first began her research on the topic of death and its representation in art, the artist was struck by societies that have acknowledged life’s inevitable end with awareness and acceptance. Ancient Egyptian, Greek, Roman, and many American Indian cultures believed that the spirits of the dead continued on, death was merely a change in existence. The Mexican Día de los Muertos tradition can be traced back to Aztec feasts where family members honored their dead and supported their spiritual journey. The Korowai people of Indonesia speak of themselves as being in the process of dying in everyday conversation. Hyolmo Buddhists in Nepal regard dying “as an intricate art to be learned…to ensure a smooth passage into the next life as well as a successful rebirth.” Chicago embarked on The End as a personal exercise in coming to terms with her own fear of death.

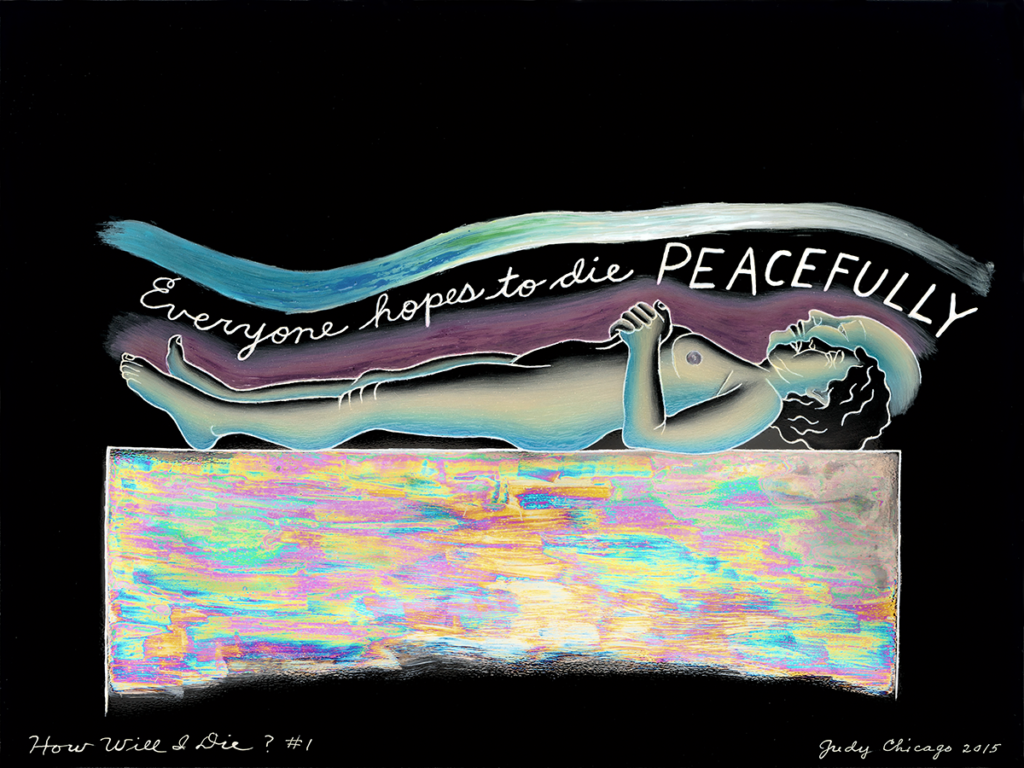

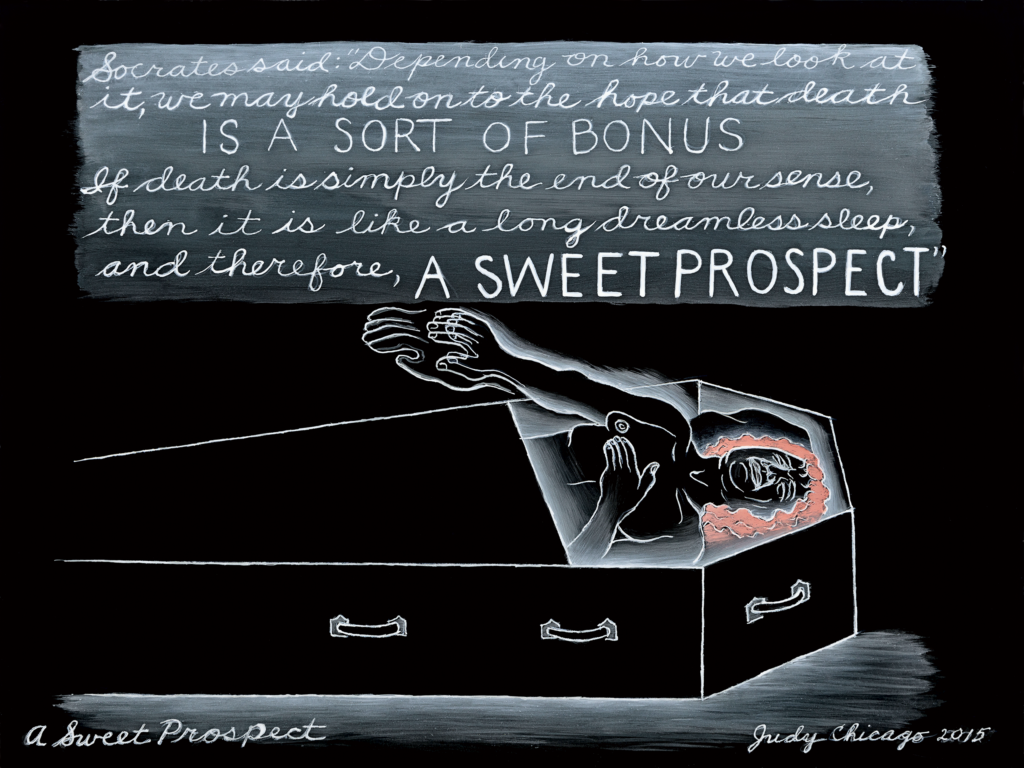

In the “Mortality” section, Chicago explores her own death across 20 black glass panels. The figure in each work has the artist’s shock of bright curls and presents a vivid vision of her eventual demise. Chicago, who says she has always been aware of her own mortality, became even more cognizant after a health scare in 2012. The works in this section are rendered in kiln-fired glass paint, an extremely time-consuming and laborious process, with multiple firings needed to achieve the artist’s desired effect. Chicago chose black glass, which is both strong and fragile, because “it seems a perfect metaphor for life.”

Handwritten text is an integral element in The End. In “Mortality,” Chicago uses writing to both comfort and question. The artist incorporates musings on death from a number of celebrated thinkers including Albert Camus, Simone de Beauvoir, and Socrates, who once said, “If death is simply the end of our sense, then it is like a long dreamless sleep, and therefore, a sweet prospect.” In startling works that envision possible scenarios surrounding her own death, Chicago asks pointed questions: “Will I die embracing the light?” “Will I die screaming in pain?” Another panel presents synonyms and metaphors for death—demise, release, oblivion, be no more—an exercise in sorting through meaning around this amorphous, unknown, universal experience.

In The End, Chicago intentionally addressed the one subject that most people in Western societies work diligently to avoid: their own impermanence. “As difficult as it was to confront my own mortality, it brought me to a place of acceptance,” Chicago said. “I hope that I will be able to face my end with courage, grace, and humor.”