Ruth Asawa (b. January 24, 1926) had no ordinary childhood. During World War II, at the age of 16, Asawa and the rest of her family were taken from their home and sent to the Santa Anita race track for six months, along with hundreds of other Japanese-American families. During Asawa’s internment, however, she had the opportunity to study with artists, art students and Disney animators, all of whom were relocated to the camp. The experiences she underwent while interred had a profound impact on her life. As the artist said in a 1994 interview, “I hold no hostilities for what happened; I blame no one. Sometimes good comes through adversity. I would not be who I am today had it not been for the Internment. And I like who I am.”

In 1943, Asawa was granted a scholarship from the Japanese American Relocation Council to go to the Milwaukee Teacher’s College in Wisconsin. However, because of her Japanese heritage, the college (now the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee) refused to grant her the bachelor’s degree she earned. After Asawa had proven herself in the art world, the university offered her an honorary doctorate in 1998. She refused. Instead, she insisted on receiving the B.A. that she had been denied in 1946.

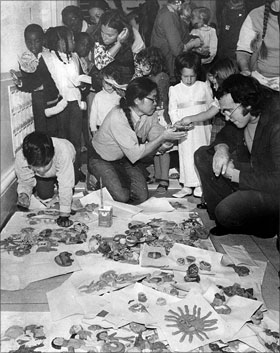

In addition to her work as an artist, Asawa has been a leading art activist. In 1968, she co-founded the Alvarado School Arts Workshop, which helps children in public schools develop academically and socially through the involvement of parents and professional artists. Focusing on arts education, the program has been integrated into 50 public schools in the San Francisco area. In 1982, Asawa began focusing her energies on creating a public high school for the arts, the School of the Arts High School (SOTA) in San Francisco. The school’s mission is to “provide a specialized high school program and learning environment which are conducive to creative and independent thinking and artistic and academic excellence for promising students of the arts.” Asawa’s commitment to arts education and advocacy has created opportunities for young students to explore their own creativity and passions.

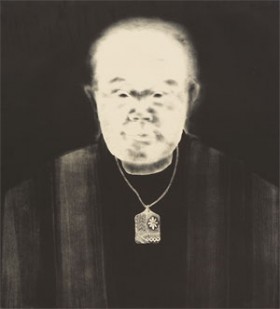

Asawa’s great personal strength and character can be seen throughout her work. In 1965, she spent two months at Tamarind, and one of the prints she created there is currently on display at NMWA in Pressing Ideas: Fifty Years of Women’s Lithographs from Tamarind. This print, Umakichi, is an image of Asawa’s father.

During the internment, Asawa did not see her father for six years (he was taken to a different internment camp and she went away to school). This poignant lithograph blurs his personally distinguishing facial features and draws focus to the eyes and nose of the figure. By focusing on these features, and therefore blurring the image of her father into a more generic image of a Japanese man, Asawa is perhaps alluding to the US government’s blind judgment of thousands of Japanese-Americans, and not seeing them as individuals whose lives they would irrevocably change.

Come see Ruth Asawa (for more information, visit her website at http://www.ruthasawa.com/) and all the other artists in Pressing Ideas: Fifty Years of Women’s Lithographs from Tamarind, on display at NMWA through October 2 ,2011.