Exhibitions of work by Audrey Niffenegger and Faith Ringgold are on view through November 10 at NMWA. At first glance their work seems quite different, but in addition to employing text in their art, they are connected by another unlikely tactic: the use of shock value to grab the attention of their audiences.

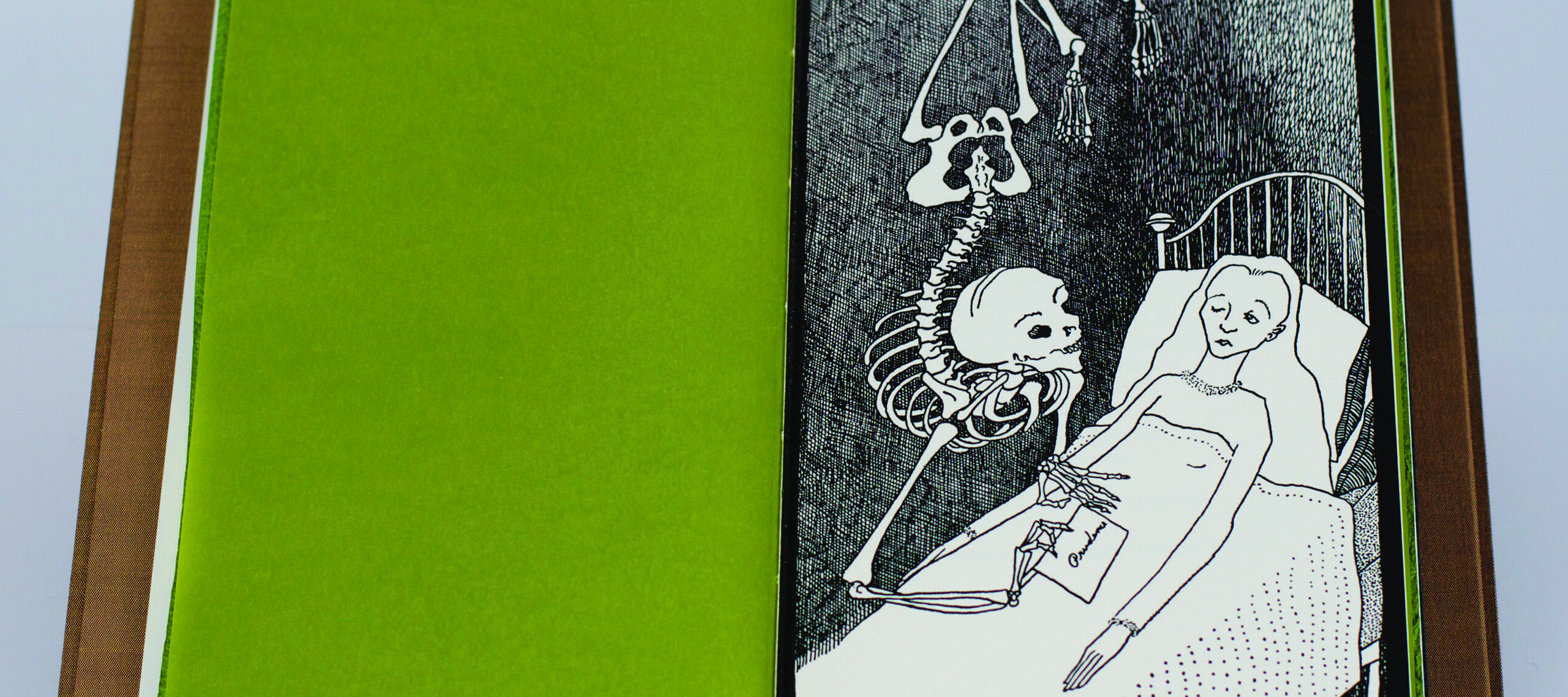

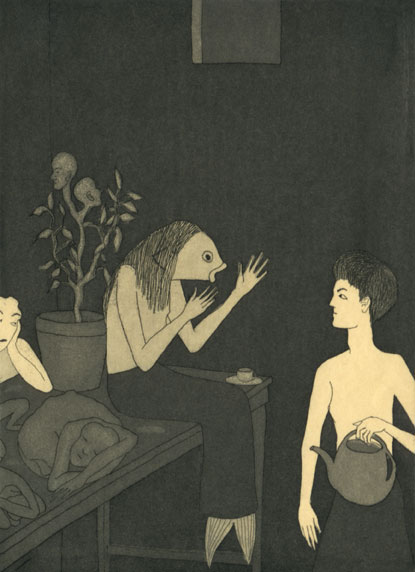

This technique is perhaps more immediately obvious in Niffenegger’s fantastical works, in which skeletons and other morbid figures intermingle with grotesque hybrid creatures reminiscent of the work of Heironymus Bosch (1450–1516) and Surrealist René Magritte (1898–1967). As Niffenegger puts it, “I use fantastic elements in my art to startle people into noticing and paying attention…strangeness makes us see more acutely”—a sentiment aligned with the early 20th-century Surrealist movement that espoused the portrayal of off-putting, illogical scenes and figures in an attempt to express the unconscious and to comment on the supposed absurdity of life. In a page from Niffenegger’s first visual Novel The Adventuress (1983–85)—the story of a brave, if ill-fated, adventuring woman created by an alchemist father—the shocking, macabre figure of a half-fish, half-human hybrid dominates the scene, sitting on a table amid other gruesome creatures (Her companions were the other Creatures the alchemist had created, from The Adventuress). Immediately reminiscent of Magritte’s 1934 The Collective Invention, a rendering of a half-woman, half-fish creature that startles viewers through the shocking nature of the juxtaposed elements, Niffenegger’s hybrid creature similarly shocks and directs attention to the strangeness inherent in nature and dreams.

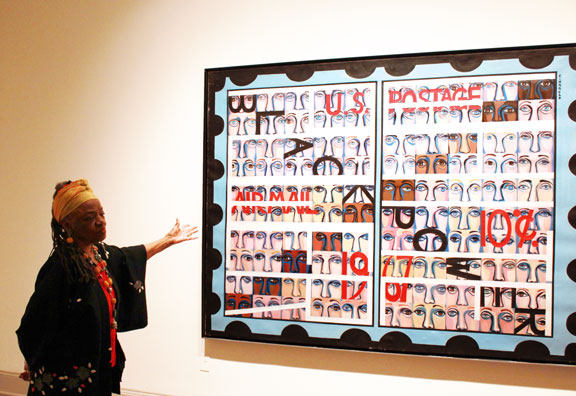

Less blatant than Niffenegger’s use of the strange and startling is Ringgold’s subtle incorporation of shocking racial language in some of her works to send strong messages about racial discrimination and inequality. Much of her art depicts strong scenes of violence, racial tension, and unease, often juxtaposed with flag imagery—the compositions point to America’s shortcomings in terms of racial progress, but several, such as Black Light Series #10: Flag for the Moon: Die Nigger, demand that the viewer take time to look closely to understand.

Without looking at its title, Black Light Series #10: Flag for the Moon: Die Nigger, 1969, at first appears to be a simple image of painted American flag, devoid of any controversy. Upon second glance, however, a word slowly becomes discernible in the starry blue portion of the flag: “Die.” Unnerving on its own, this word prompts viewers to look for other hidden words on the flag. Suddenly, the horizontal red and white stripes of the flag do not appear uniform, and when viewed from the side, reveal the word “nigger” (frequently incorporated into Ringgold’s art).

Unlike the immediate shock of Niffenegger’s odd creatures, Ringgold’s jaw-dropping message is discernible only after a time of concentration—likely an intentional choice on the artist’s part to prompt viewers to take time and consider the context and meaning of the work. Created in the year of the Apollo 11 moon landing, Flag for the Moon is a commentary on the status of American progress from the perspective of an African-American in the 1960s, drawing attention to the fact that, while astronauts may have been landing on the moon, black Americans were still suffering. Additionally, Ringgold may have considered her flag—and its shocking phrase in particular—to be a better alternative to the flag actually planted on the moon, considering that vast sums of money were spent on the space program by the U.S. government instead of being dedicated to ending racial disenfranchisement at home.

Vastly different in their styles, mediums, and messages, both artists currently featured at NMWA employ clever devices to tell stories, make statements, and enrapture observers. While Niffenegger fills the role of fantasy weaver and Ringgold that of political activist, both women are visionaries in their own right who have left, and continue to leave, their unique imprint on the art world.