When Anna Ancher painted rooms in her family home in Skagen, Denmark, she presented very different images when she associated herself versus her husband with the represented space. Depictions of her artist husband, Michael Ancher, in prosperous surroundings diverge from paintings of her own space, which she presented simply, often devoid of inhabitants or ornamentation.

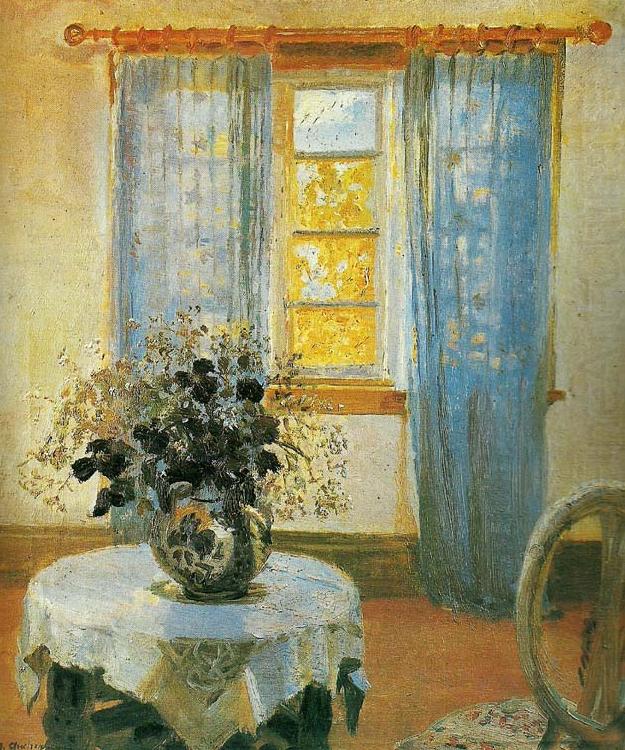

Interior with Clematis (1913), for example, reduces Anna Ancher’s studio—her only private room—to a table, flowers, and a large window. She leaves the space ambiguous by eliminating both herself and expected objects. In contrast, Ancher depicts her husband surrounded with signifiers of his profession and social status. These differences underscore Anna Ancher’s independence and the modern orientation of her art.

In Ancher’s paintings of Michael, he emerges as a successful, well-fed, bourgeois artist. In Breakfast before the Hunt (1903) he eagerly attacks an ample morning meal. Nearby, his gear signals the imminent excursion, and the dog sits alert in anticipation. Her detailed rendering of the table setting and the upholstery announce Michael’s financial achievement as the provider of a comfortable home. His prosperity is also evident in The New Hunting Boots (1903), where he contentedly stretches his stockinged feet across the big parlor rug. The gold chain of a pocket watch outlines his full, round belly. His boots’ soft, supple leather gleams. Finally, in Ancher’s 1920 portrait of Michael in his spacious studio, he appears with brushes in hand, dressed in vest and coat as if to meet a wealthy client. Giant canvases and heavy furniture surround him. Ancher’s hint of a painted seascape on the wall alludes to the paintings of fishermen that built Michael’s career.

Ancher does not invite viewers to feel the same familiarity with her personal space. Although her studio was adjacent to Michael’s in the house, its character appears opposite. In Evening Sun in the Artist’s Studio (after 1912), her focus on tactilely rendered light indicates neither her profession nor her gender. The modest proportions, austere furnishings, and the absence of painter’s tools obscure Ancher’s celebrity as the 1913 recipient of Denmark’s prestigious Ingenio et Arti award.

In creating these images, Ancher implies that her role is observer, rather than subject. While Ancher signified Michael’s bourgeois masculinity, she omitted references to herself as his female counterpart, imperceptibly reversing gender roles. Like most middle-class males in this period, Michael could traverse freely the boundaries separating the public arena from the private zones of the home.¹ Ancher’s letters reference Michael’s travels while she remained in Skagen; her own trips abroad were always in his company.² In these paintings, however, he is home and she is absent.

Ancher’s refusal to define herself in relationship to the home distinguished her from Scandinavian women colleagues. For example, Norwegian Modern Breakthrough author Amalie Skram described feminine spaces with stifling details of shaded lamps, velvet sofas, embellished screens, large stoves and lingering smells.³ Furthermore, Ancher continued to engage professionally in the public sphere, marketing her work through exhibitions and dealers, unlike Marie Krøyer in Skagen or Karin Bergöö Larsson in Sweden. Both those women interrupted their painting practices to produce decorative domestic objects for their homes. Remarkably, Anna Ancher’s physical absence from her representations of home quietly asserted liberation from its traditionally restrictive boundaries.

Notes:

1. Suzanne Singletary, “Le Chez-Soi: Men ‘At Home’ in Impressionist Interiors,” in Impressionist Interiors ed. Janet McLean (Dublin: National Gallery of Ireland, 2008), 30-51.

2. Lise Svanholm, ed., Breve fra Anna Ancher [Letters from Anna Ancher], Denmark: Gyldendal, 2005, 99-102.

3. See for instance Amalie Skram’s description of Marie Hansen’s house in Constance Ring (Norway, 1888). Trans. Judith Messick with Katherine Hanson (1988; repr. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2002), 91.