The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction, the newest body of work by iconic feminist artist Judy Chicago, continues the artist’s practice of tackling taboo subjects. In these works, she offers a bold reflection on mortality and the destruction of entire species. Visually striking and emotionally charged, the exhibition comprises more than 35 paintings on black glass and porcelain, as well as two large-scale bronze reliefs. On view September 19, 2019 to January 20, 2020.

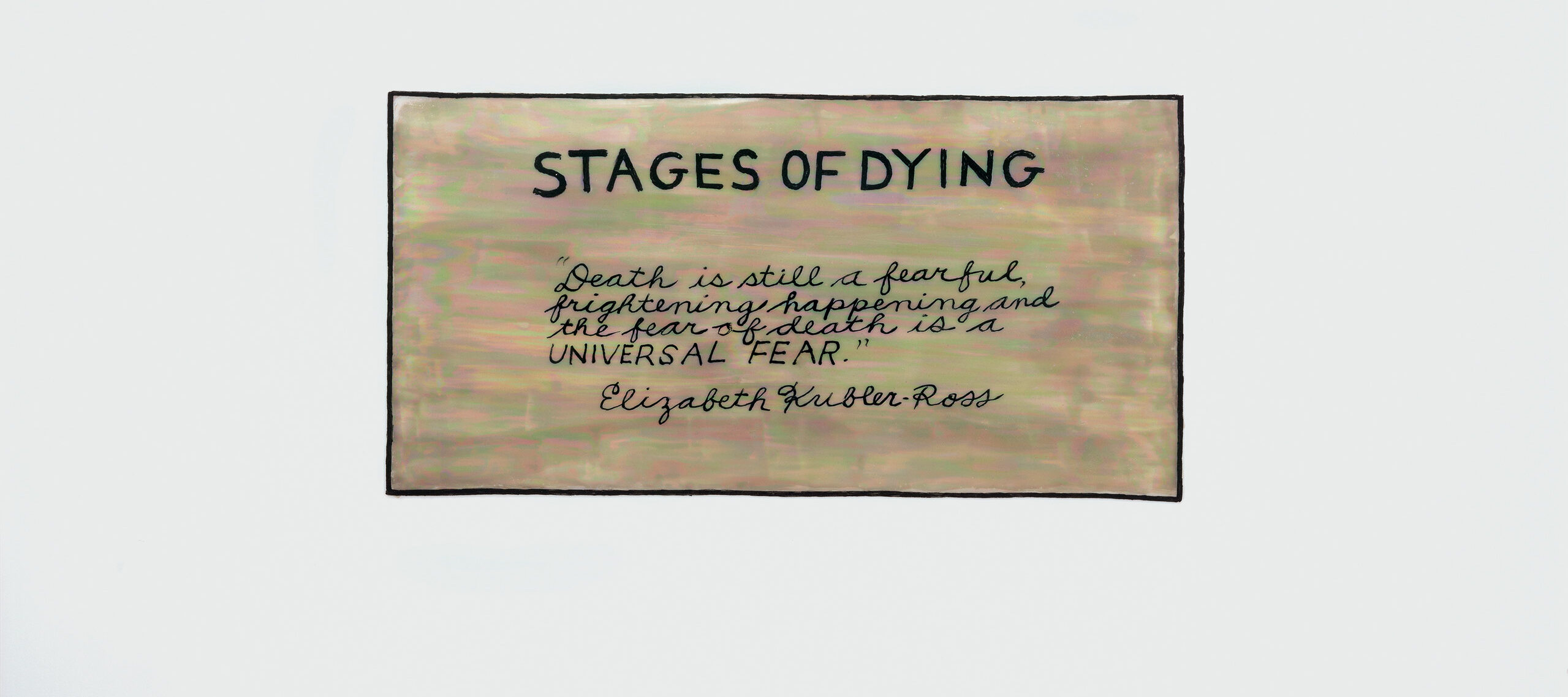

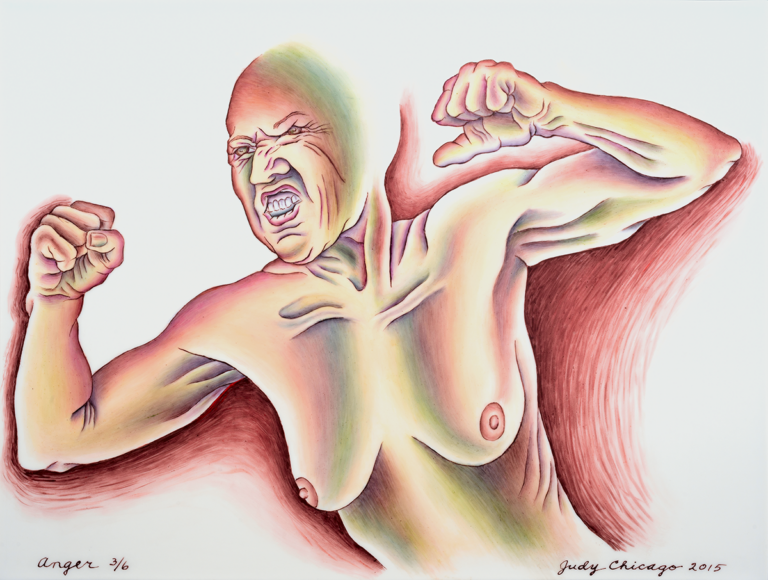

“Death is still a fearful, frightening happening and the fear of death is a universal fear.”—Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

In 1969, Swiss-born psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (b. 1926) published On Death and Dying, a groundbreaking book in which she first proposed the five stages of grief, a common emotional cycle for those who have lost a loved one or who are facing their own mortality. This model, which includes denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance, has become a prominent framework for humans to understand our complicated and multifaceted response to loss. Kübler-Ross did not arrive easily at her pioneering work. Her father was strictly opposed to her studying medicine, encouraging her instead to become a secretary or maid. And in 1958, she was disqualified from a residency in pediatrics because she was pregnant, though this led her to accept one in psychiatry.

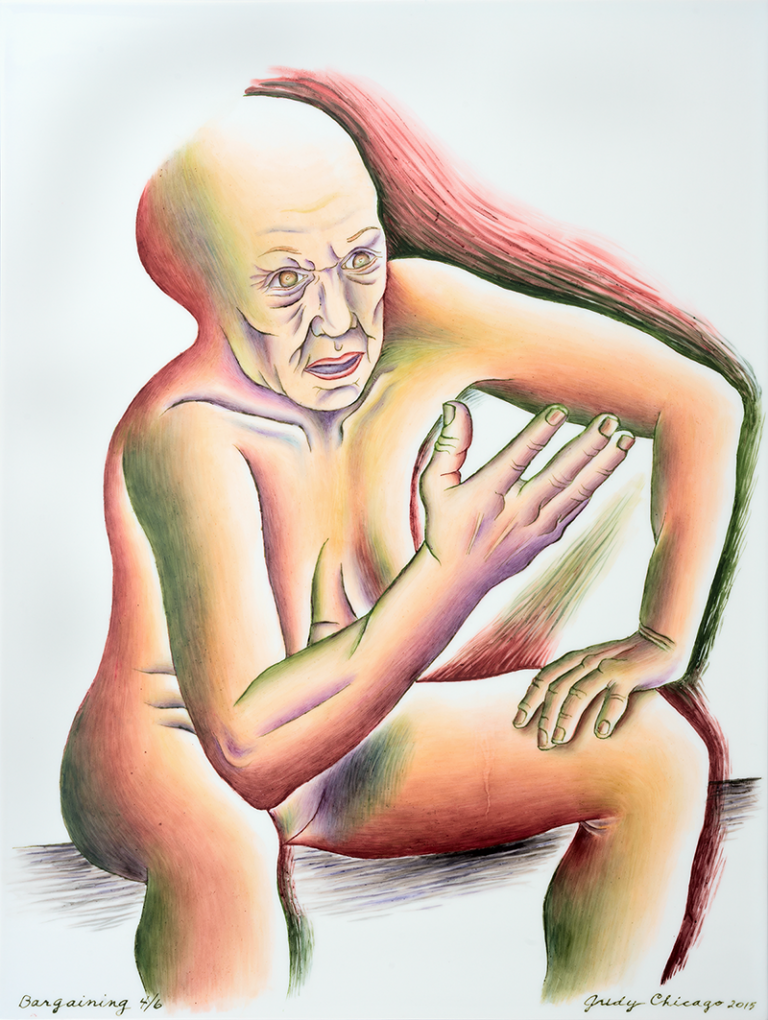

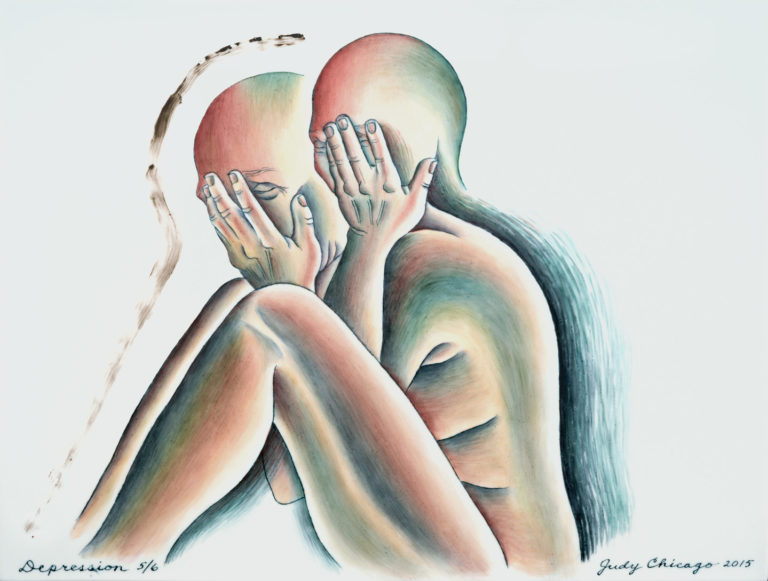

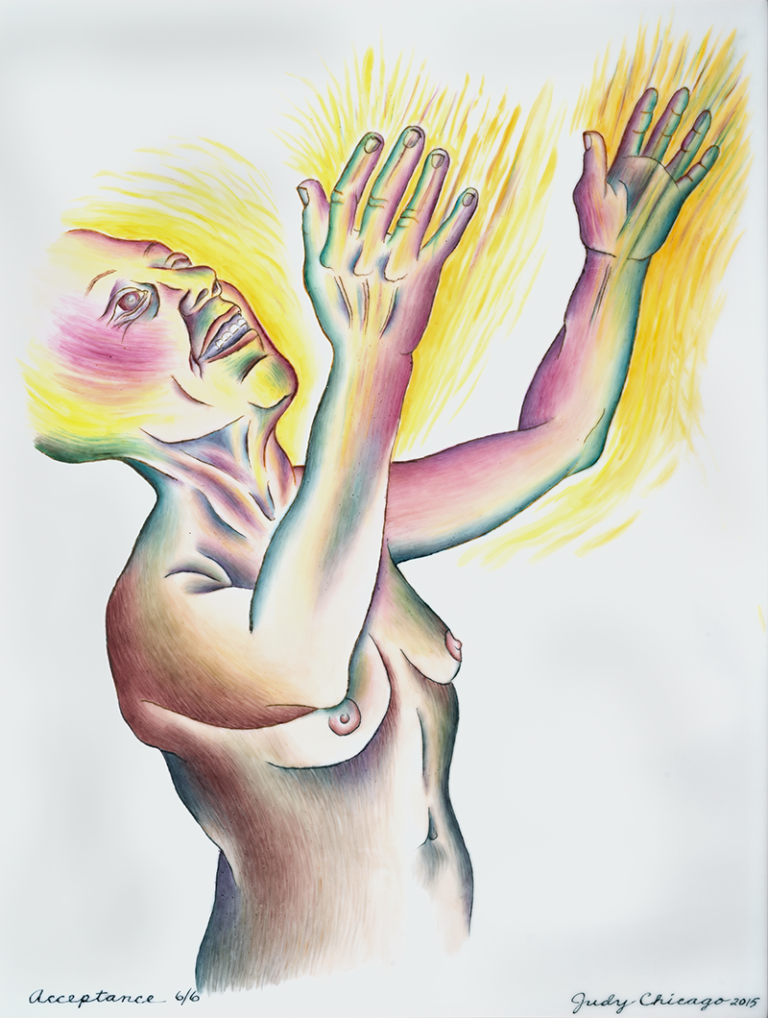

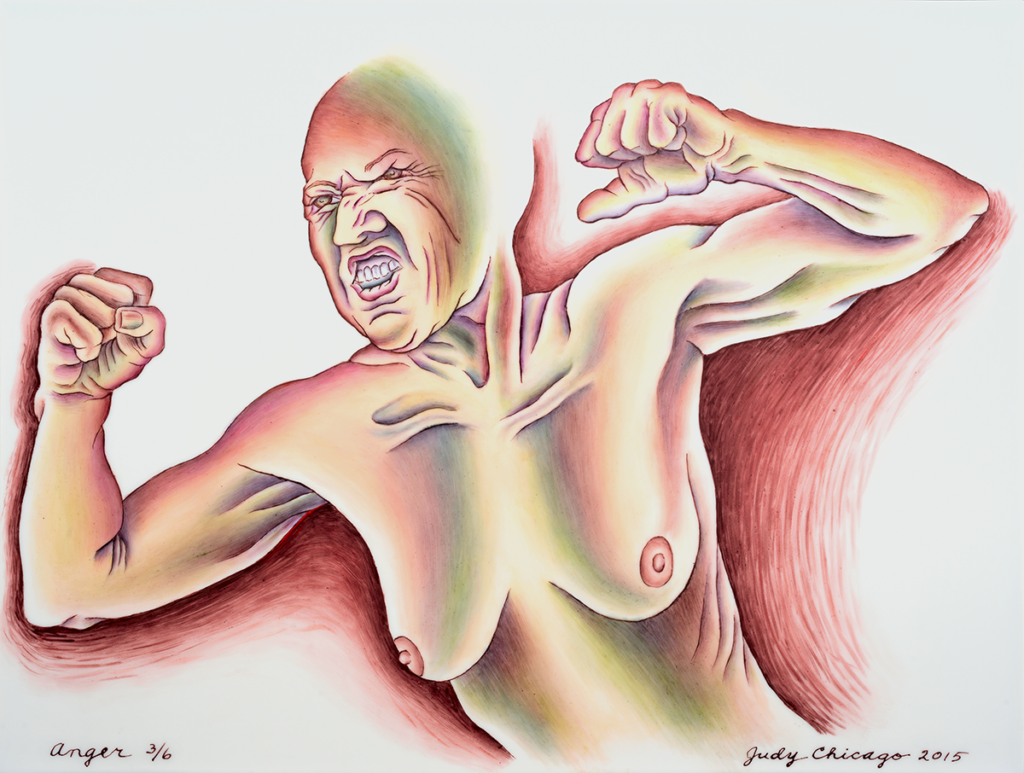

Continuing her commitment to centering women in history, as she did in The Dinner Party, Judy Chicago (b. 1939) draws on Kübler-Ross’s work for “Stages of Dying,” the first section of The End. Chicago represents these stages of grief and simultaneously reckons with her own mortality.

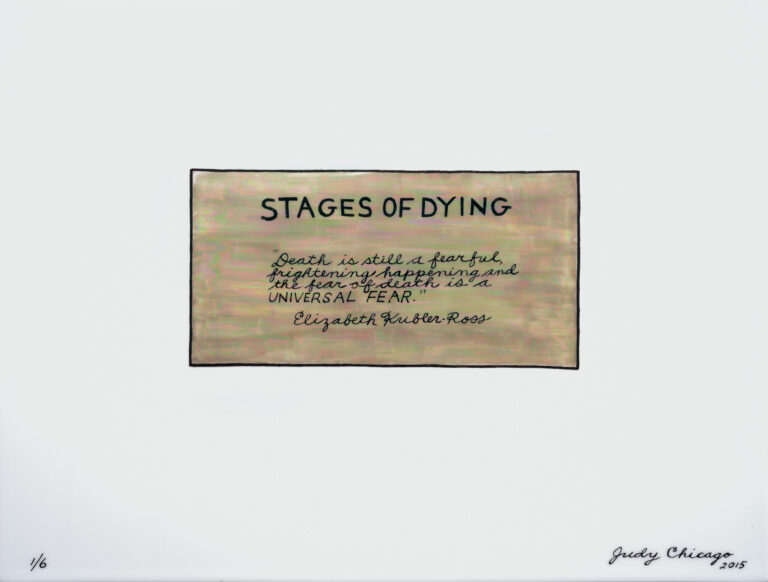

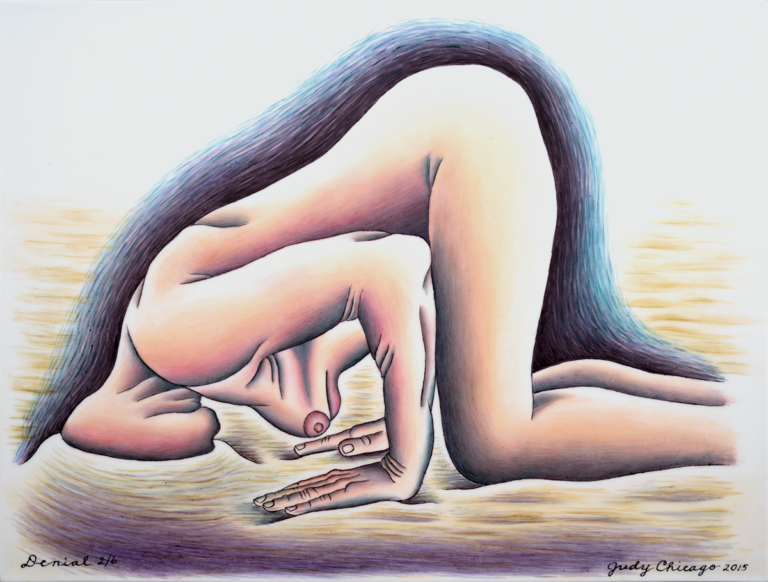

The main figure in “Stages of Dying” is a nude older woman who shares facial characteristics with Chicago. However, in choosing to portray the woman without hair, Chicago removes one of her own most recognizable traits, her short, vibrantly hued curls. The baldness of the figure renders it somewhat androgynous and, according to Chicago, makes it an archetypal “everywoman,” a universal figure to whom death will eventually come. Chicago presents an aged body that is far less prevalent than the idealized inventions of (mostly) male artists over the centuries. In lieu of a youthful and supple form, the artist gives us a wiry and wrinkled protagonist who refutes the trappings of stereotypical femininity.

The “everywoman” radiates with colored auras in each scene. In “Anger” the figure is charged with a deep red border that travels along her arms, torso, and neck. In “Depression” the figure emanates a melancholy teal. “Acceptance” is a vibrant and revelatory conclusion: the figure looks skyward and glows in bright yellow. Kübler-Ross built her theory through extensive interviews and research, and Chicago adds a visual dimension to this framework with her startling images and expressive colors.

Although Kübler-Ross understood the fear of death as universal, she conceived of the stages of grief as a process for healing. Chicago’s work process may have echoed that model. As the artist says, “As difficult as it was to confront my own mortality, it brought me to a place of acceptance.”