Ideas about place are integral to the work of Suchitra Mattai (b. 1973, Georgetown, Guyana). The artist’s ancestral roots lie in India, via forebears who migrated as indentured laborers to Guyana, on the Caribbean coast. Mattai grew up in Guyana and Canada before settling in the United States. While preparing for her NMWA exhibition, Myth from Matter, the artist spoke with Assistant Curator Hannah Shambroom. In the first post of a two-part series, hear from Mattai about her family history and her exploration of materials and techniques.

Hannah Shambroom: You started your career as a painter and then began shifting toward sculpture and installation works. Can you talk about that transition?

Suchitra Mattai: Throughout my art education I was interested in painting, drawing, and sculpture. After my undergrad years, I moved to New York and took post-baccalaureate sculpture classes at Pratt Institute. As a child, I also learned fiber-based practices from my grandmothers on a much smaller scale. I rarely married the two in my early work.

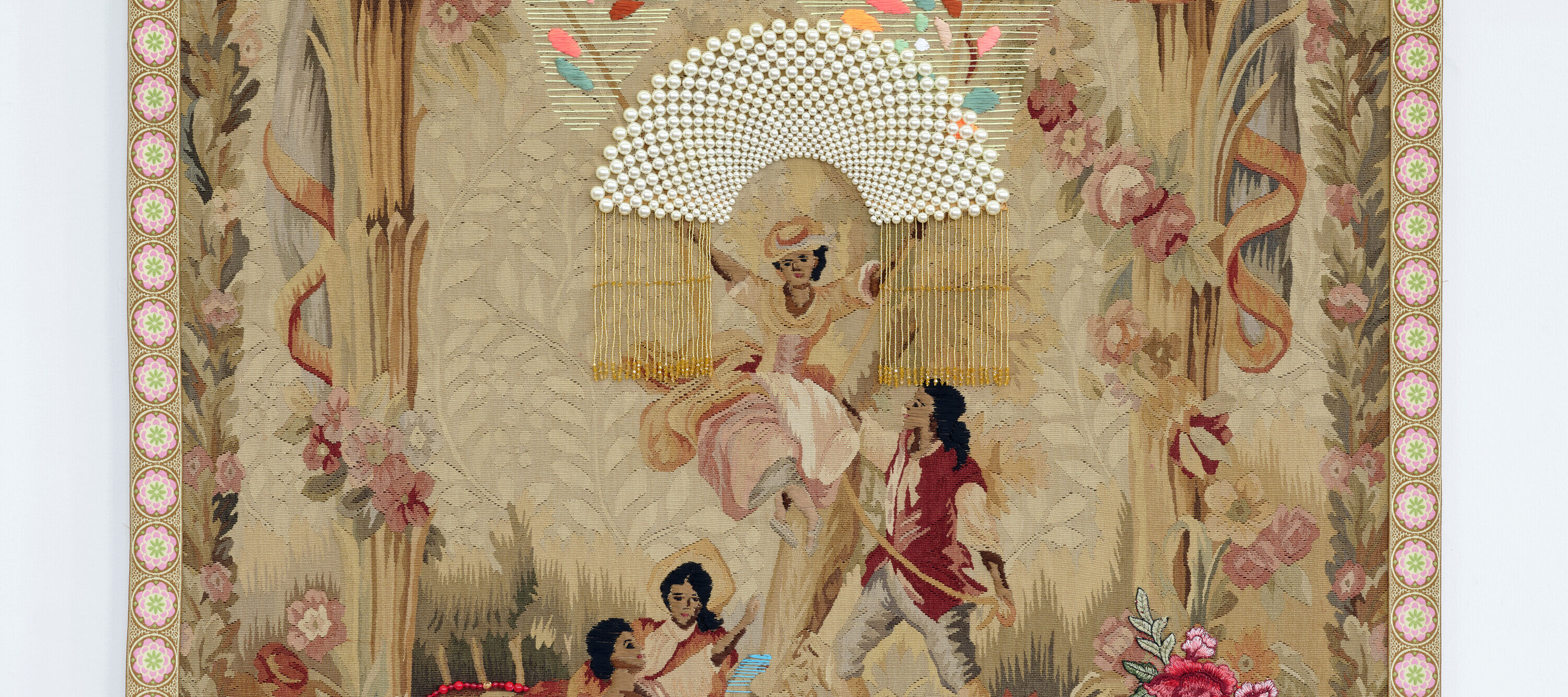

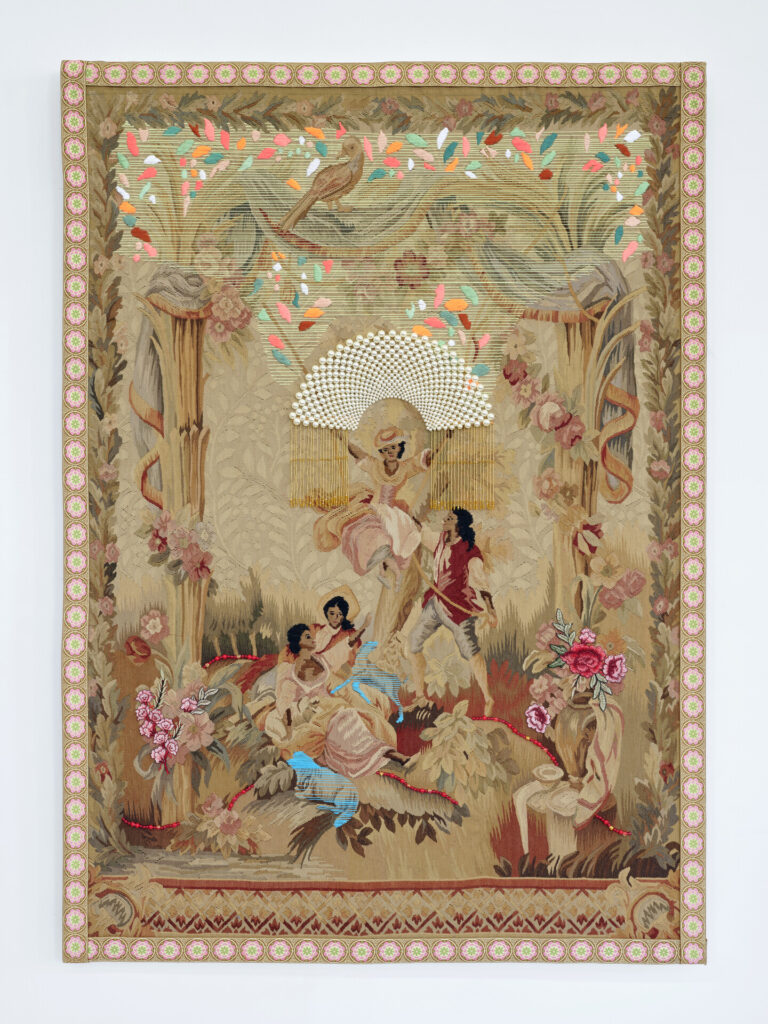

In 2018, I was given the opportunity to participate in and have a commission for the Sharjah Biennial in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and that project was my first massive installation. Part of it involved eight large-scale tapestries, along with video and found objects. Since then, my mind, my practice—everything has expanded. I see my practice as one that is not just experimental and intuitive, but also has no limits.

HS: In several of the works on view—installations and tapestries in particular—you use a distinctive technique that you call sari weaving. How did you develop this practice?

SM: It’s not traditional weaving at all. I use a one-inch-by-one-inch grid, with a rope net. It’s almost like large-scale embroidery, because you knot, you use strips of saris as embroidery floss, and you go back and forth, using your hand as the needle.

A lot of craft processes, such as needlepoint, use a grid. But I also have a math background, and the grid felt natural to me. I knew I wanted to use saris in some way—to have them be recycled and to evoke the sense of bodies in space.

HS: You’ve also described your style as maximalism inspired by Caribbean and Guyanese culture. What does that mean to you?

SM: The history of my ancestral lineage can be described entirely through color, because South Asian culture is very colorful. The outfits we wear—the saris, the lehenga, the outfits for rituals, the decorative elements that we use for weddings—everything is so rich in color. And then it moves to the Caribbean, where there are additional influences, like Carnival and other festivals, that affect what people use to dress up and create costumes. The Caribbean is very, very colorful.

When I say “maximalist,” it’s about layers that all have a rich intensity, not just from color, but from making things with your hands. There’s a “do it yourself” mentality in both the Caribbean and in South Asia, and that plays a huge role in my practice—the sense of finding what you need, or combining objects in strange and interesting ways.

HS: I’m interested in the different types of found and vintage materials that you use. Often, your materials come from very specific sources. For example, in the work love, labor, and the pursuit of happiness (2022) you use vintage saris, but also your mother’s sari.

SM: Ultimately, I’m a storyteller, and I want to tell the stories of people whose voices haven’t been heard. I start with the stories of my own family, who were indentured laborers during British colonial rule. When I incorporate an object or material that’s more intimate, I’m honoring their presence, their stories. It brings me great joy to do that.

This conversation is adapted from an interview for the exhibition catalogue Suchitra Mattai: Myth from Matter (2024). The exhibition is on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts through January 12, 2025.