Throughout history, artists have imbued their works with the language of symbols to deepen meaning, create tension, and provide visual impact. Chinese painting, for example, has a rich history in which works often feature symbolic plants and animals from the natural and supernatural worlds. Chinese-born American artist Hung Liu (b. 1948) employs traditional Chinese motifs in her works on view in the special exhibition Hung Liu In Print, layering and superimposing them upon images of often anonymous figures from history, including 19th-century Chinese courtesans, laboring farmers, and migrant workers.

Liu’s 2005 series “Seven Poses” features layered imagery, frequently including animals that have symbolic meanings within Chinese culture. In one print from “Seven Poses,” a large crane fills the foreground, while a seated woman holds an open fan. The crane can be a symbol of longevity, happiness, and eternal youth. In another image, a woman lies on a couch that melds with the cherry blossom tree branches around her. Beneath her is a white swan, a symbol of grace and beauty.

In these works, the aesthetic beauty of the animals is aligned with that of the women, prostitutes who were prized for their beauty, but whose identities outside of their images are now lost. They are re-contextualized and collaged with these recognizable Chinese cultural symbols. When presented without context, they become cultural prototypes. Liu’s layered surfaces and expressive, calligraphic brushstrokes highlight this long process of image change and how a symbol can be meaningful or mostly aesthetic, depending on context.

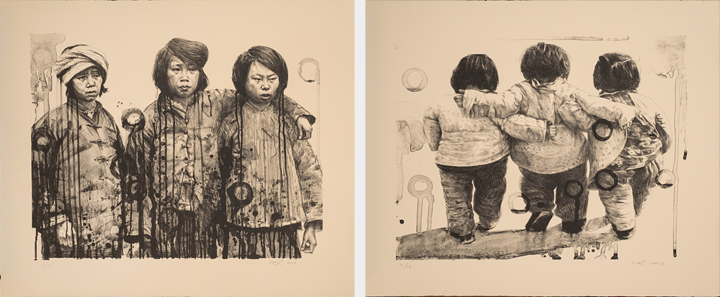

Another symbol that reappears in often Liu’s works is the circle. In Chinese writing, a circle denotes the end of a sentence. In Zen Buddhism, the circle alludes to emptiness, wholeness, and the cyclical nature of everything. In Liu’s words, circles are “a kind of Buddhist abstraction.” They cover the surface of Sisters in Arms I and II (2004), works depicting three women at different stages in life. In playful youth or hardened adulthood, they still stand arm in arm. In these detailed lithographs, the circles unite the two images, as well as provide a visual link to the Liu’s oeuvre.

Ultimately, Liu’s depictions of anonymous figures like these prostitutes and laborers are a humanizing attempt to insert them back into the canon of memory. “I communicate with the characters in my paintings, prostitutes—these completely subjugated people—with reverence, sympathy, and awe,” says Liu. By combining them with recognizable and distinct imagery from Chinese culture, she asserts their place in Chinese history.