July is Disability Pride Month. As part of NMWA’s 2024 #5WomenArtists campaign, which focuses on disability activism and advocacy in the arts, we spoke with art historians and disability advocates who are working at this intersection.

Today, hear from Phillippa Pitts, a historian of American art and visual culture. Pitts embarked on her PhD after a decade in museum practice and is the current Wyeth Foundation Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

1. Tell us about your work.

My current project is an art history of pharmaceuticals. We often think about drugs within a patient-provider framework or as biochemical substances that produce physical changes in an individual body. But the lived experience of taking medicine is so much more complex, filled the with aspirations and anxieties of individual experience and the preconceptions and prejudices that surround different drugs. Looking at pharmaceuticals through a visual and cultural lens, rather than a medical one, allows us to access these kinds of stories. As an art historian, I’ve also found that bringing human questions of health and illness back into the conversation illuminates new elements within even well-known works of art.

2. How did you come to this topic?

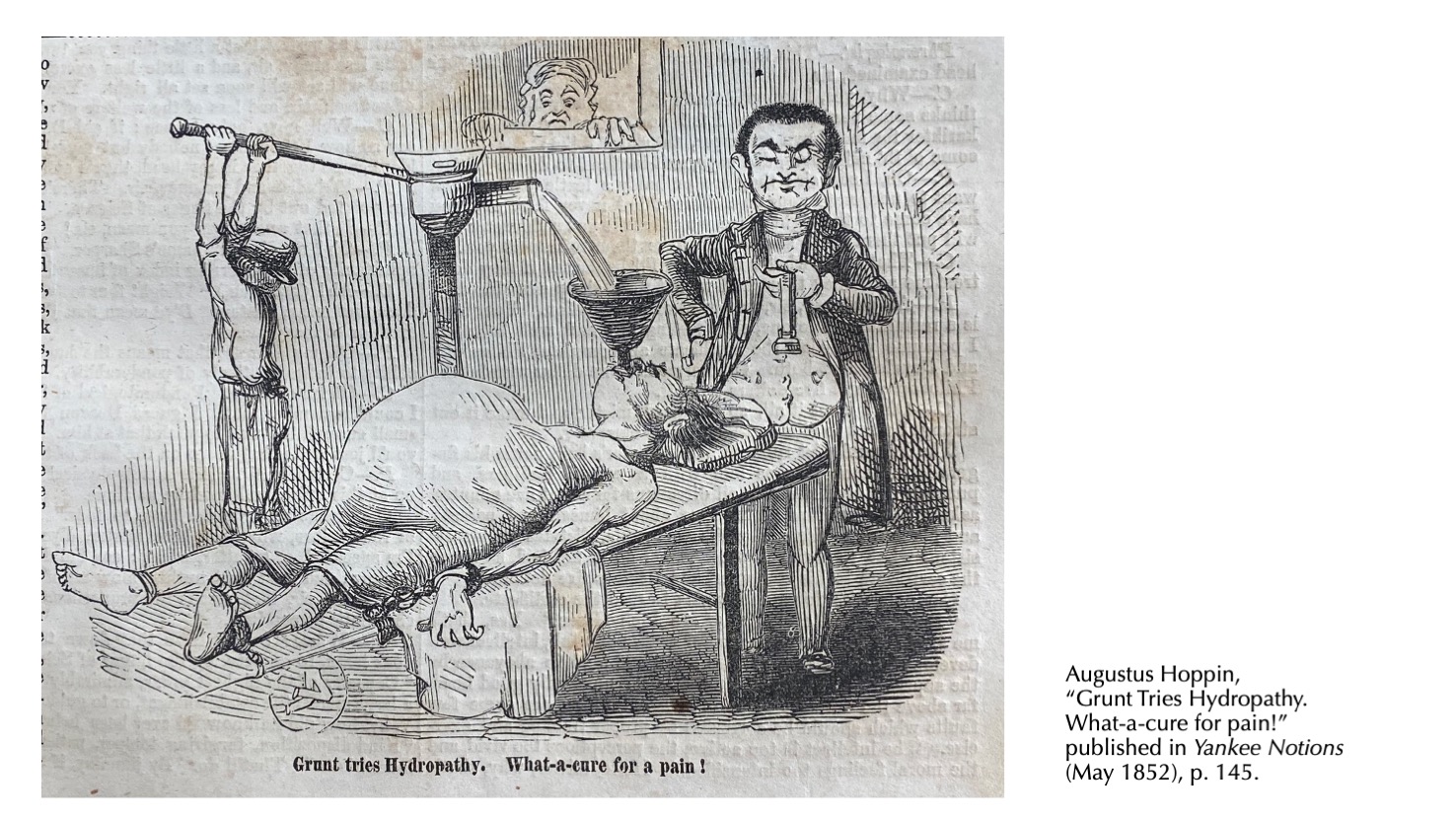

It was both a natural progression and a complete accident. Before returning to doctoral study, I worked in museums for a decade, including accessibility advocacy. I was fortunate to have wonderful mentors who helped me unlearn ideas about what it is to exist in this world within a wide range of bodies. Years later, I was browsing through a 19th-century humor magazine when I came across a cartoon series chronicling one man’s fictional struggle with 19th-century medical treatment. It included an image of a Frankenstein-esque doctor physically inflating his patient like a water balloon! The project grew from there, bringing an art history and disability studies perspective to a topic that’s usually framed in terms of science and medicine.

3. Why is this topic important now?

In the early 19th century, the United States declared itself a “medical democracy,” granting its citizens the “freedom” to choose their own medical treatment—however horrid or hazardous. While most of the eclectic, electric, magnetic, and mesmeric cures have disappeared, the ideas that spread during this period still hold sway. These range from big concepts, such as binding health to individual responsibility, to odd quirks, such as why drugstores stock a little bit of everything.

When COVID-19 hit, these ideas jumped to the forefront of public discourse once more, in the form of vaccine hesitancy, healthcare disparities, the rise of deregulated supplements, and an increase in openly eugenic rhetoric. My project helps us see that these contemporary controversies are not surprising aberrations; they have deep roots in American culture and need to be addressed as such.

4. What does “disability activism in the arts” mean to you?

Inclusion involves more than ramps and braille. It also requires that we shift our cultural narratives. We must push back on major misconceptions, such as the conflation of disability with inability. We also need to challenge the idea that these are special topics of interest to only a small number of people.

My research shows how the arts shored up dominant narratives around health and ability, from medicine bottles fabricated in the shape of George Washington’s head to expansive landscapes filled with medicinal plants. If art has the power to cement these ideas, it also has the power to break them down. We see that in the work of artists including Erica Lord, Christine Sun Kim, Yayoi Kusama, and Shannon Finnegan, whose work chips away at the weak points within ableism’s structural logic.

5. Who has been a powerful influence on you and your work?

The women of Cultural Access New England, especially Maria Cabrera and Hannah Goodwin, who were so generous with their time and connections as I started out in professional accessibility work. This is not the kind of work that you can do alone. My community is constantly expanding, bringing in artists, archivists, scholars, and activists, but those early conversations will always shape the way I think and work.