July is Disability Pride Month. As part of NMWA’s 2024 #5WomenArtists campaign, which focuses on disability activism and advocacy in the arts, we spoke with art historians and disability advocates who are working at this intersection.

Today, hear from Natalie Wright, a design history PhD candidate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who is writing a history of disability and dress in the post-war United States. Wright is currently the 2023–24 George Gurney Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

1. Tell us about your work.

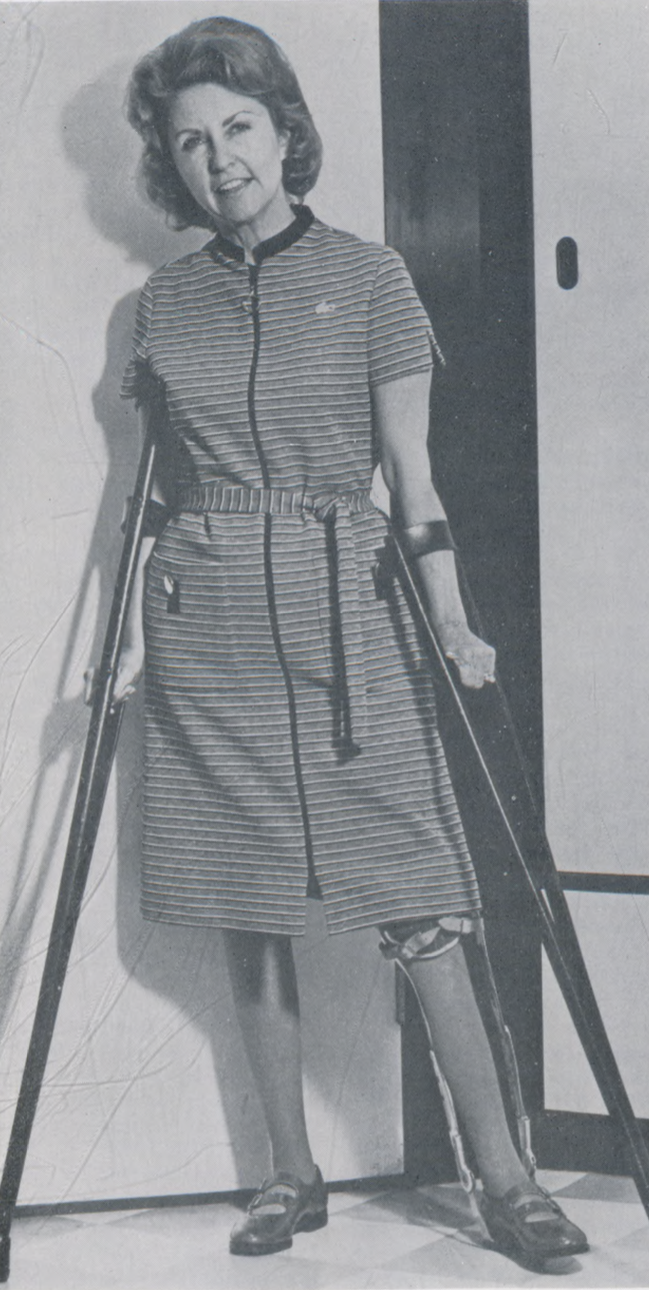

My dissertation recovers a campaign in the postwar United States to design “functional clothing” for disability. These garments made use of new technologies such as Velcro to ease dressing and undressing. The women behind this effort were home economists, government policy makers, fashion designers, and medical professionals. My work involves pulling these designs and their documentation from obscurity. I also unpack the ideology that they inculcated. The ultimate goal of these garments was to help wearers perform work. This connection to labor is how I read the idea of “function” in relation to both designs and people.

2. How did you come to this topic?

In 2017, I was helping to curate an exhibition on the childrenswear designer Florence Eiseman (1899–1988) when I learned that she designed clothing for children with disabilities in the early 1960s. From there, the project kept growing. Eiseman was one of roughly 30 designers who contributed to the “Functional Fashions” line for disability. Home economists developed “functional clothing” for disability even earlier; “sheltered workshops” trained disabled folks to produce and sell clothing; and women taught “fashion therapy” courses in psychiatric hospitals. At every turn, the archives revealed more. I couldn’t let it go, and soon enough, it was my dissertation project.

3. Why is this topic important now?

Disability history is always important. But I think this topic resonates today because disability and dress are in the news. Brands are creating “adaptive” clothing and disabled models are on the covers of magazines. By researching antecedents, I can show how accessible designs are not, and have never been, neutral. For example, these early designs were part of deinstitutionalization efforts—if someone could dress and undress themselves (a key part of performing “function”), they could remain at home with their families. Clothing informed the medical and societal evaluations that constructed disability around function and which we still grapple with today.

4. What does “disability activism in the arts” mean to you?

It means moving beyond disability as a contemporary access problem to be solved. David Gissen wrote about this very beautifully in his book The Architecture of Disability: Buildings, Cities, and Landscapes Beyond Access (2022). That doesn’t mean abandoning access needs. It means curating exhibitions in museums in which disability is discussed as a culture with a history, as well as adding more museum seating for visitors to rest. It means discussing an artist’s disability in ways that refute widespread misconceptions about disability, including that it may be incidental or even unrelated to their artwork.

5. Who are the biggest influences on you and your work?

I would like to call out the work of my colleagues and mentors who are women working at the intersection of disability history and design/material culture: Bess Williamson, Katherine Ott, Jaipreet Virdi, and Natalie Kane. Katherine Ott’s work on prosthetics, and public disability history more broadly, remains field defining. Bess Williamson established 20th-century histories of design and disability, and Jaipreet Virdi has written on deaf histories, most recently on the artist Dorothy Eugénie Brett (1883–1977) and the “disabled gaze” in her paintings. Natalie Kane is undertaking a long-term collecting and curatorial project about design, disability, and identity.