Photography forms a core part of NMWA’s collection. Now, with a major donation of works from renowned photographer Joanne Leonard (b. 1940), the museum is able to more fully tell the story of women photographers. NMWA curator Ginny Treanor spoke to Leonard about how she got started, themes in her work, and the influence of her long career.

Ginny Treanor: How did you come to work in photography?

Joanne Leonard: I graduated from [University of California] Berkeley with a social sciences degree, but I also studied art there. At the time, there were no photography courses, so I also took classes at a technical college. After that, I bought my own enlarger and built darkrooms for myself in closets within rented spaces. In the early 1960s, I lived in West Oakland, California, where I began to photograph. In 1968, I had my first exhibition at San Francisco’s de Young Museum, and then I was invited to be the official photographer for the American Olympic team at the 1972 Olympics in Sapporo, Japan. My “life in photography” might be said to have gone forward from there.

GT: The first work you ever exhibited in a museum was Sonia (pregnant woman hanging laundry) (1966). I imagine that this was a shocking image for the time. What was the reaction to it?

JL: I had printed the photograph very small—only 3 ½ in. square—and surreptitiously while at work in a commercial photo lab. Perhaps [its size] helped make it acceptable in its early debut? By 1970, it was reproduced in the Life Library of Photography’s Great Themes volume, so this photograph had some unexpected respectability. By contrast, Journal of a Miscarriage (1973), which was made after my own miscarriage that year, was not readily received. It was only published in its complete form in 2008 in my own book Being in Pictures: An Intimate Photo Memoir.

GT: You’ve used the term “intimate documentary” to describe your work. How do you define that term?

JL: My definition is meant to go against the typical understanding of “documentary photography.” Documentary is generally conceived to define photographs that look outward—at and into the lives of others—and is associated with a degree of “objectivity.” I use the term “intimate documentary” as almost an oxymoron—to claim “documentary” as (at least partly) a subjective, personal, and inward-looking process.

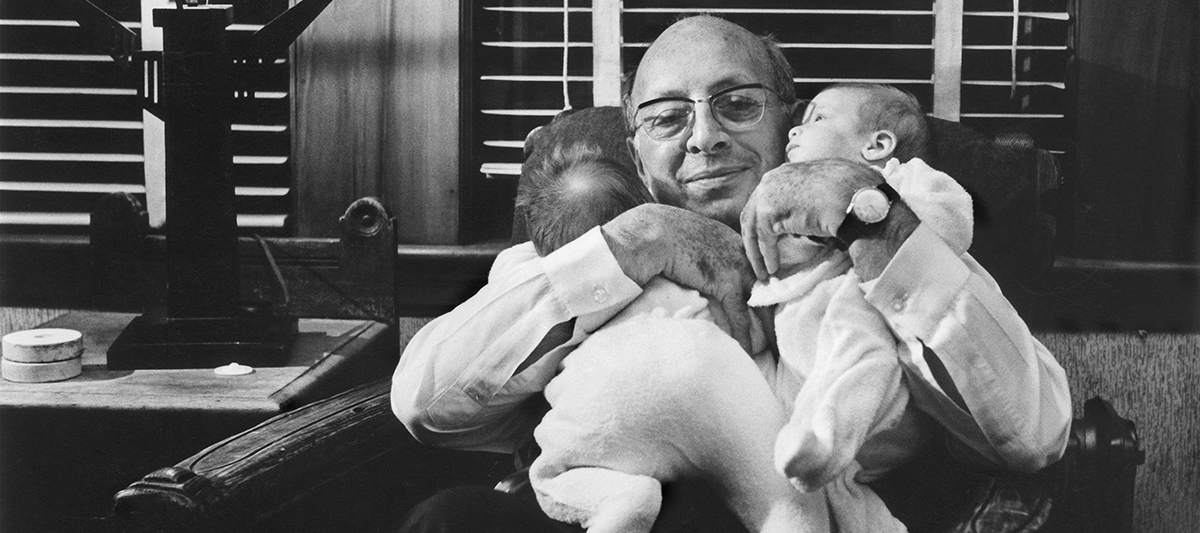

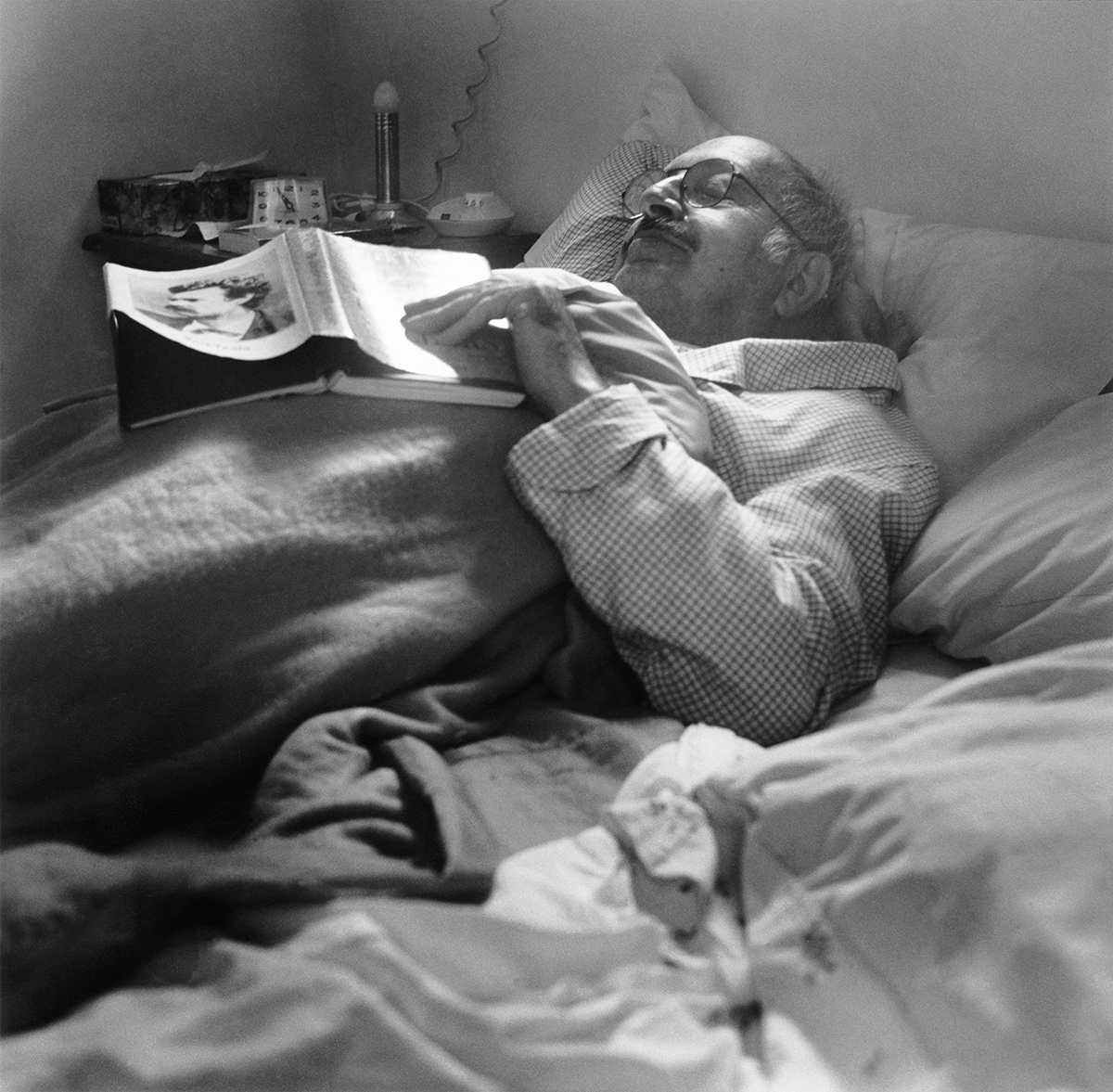

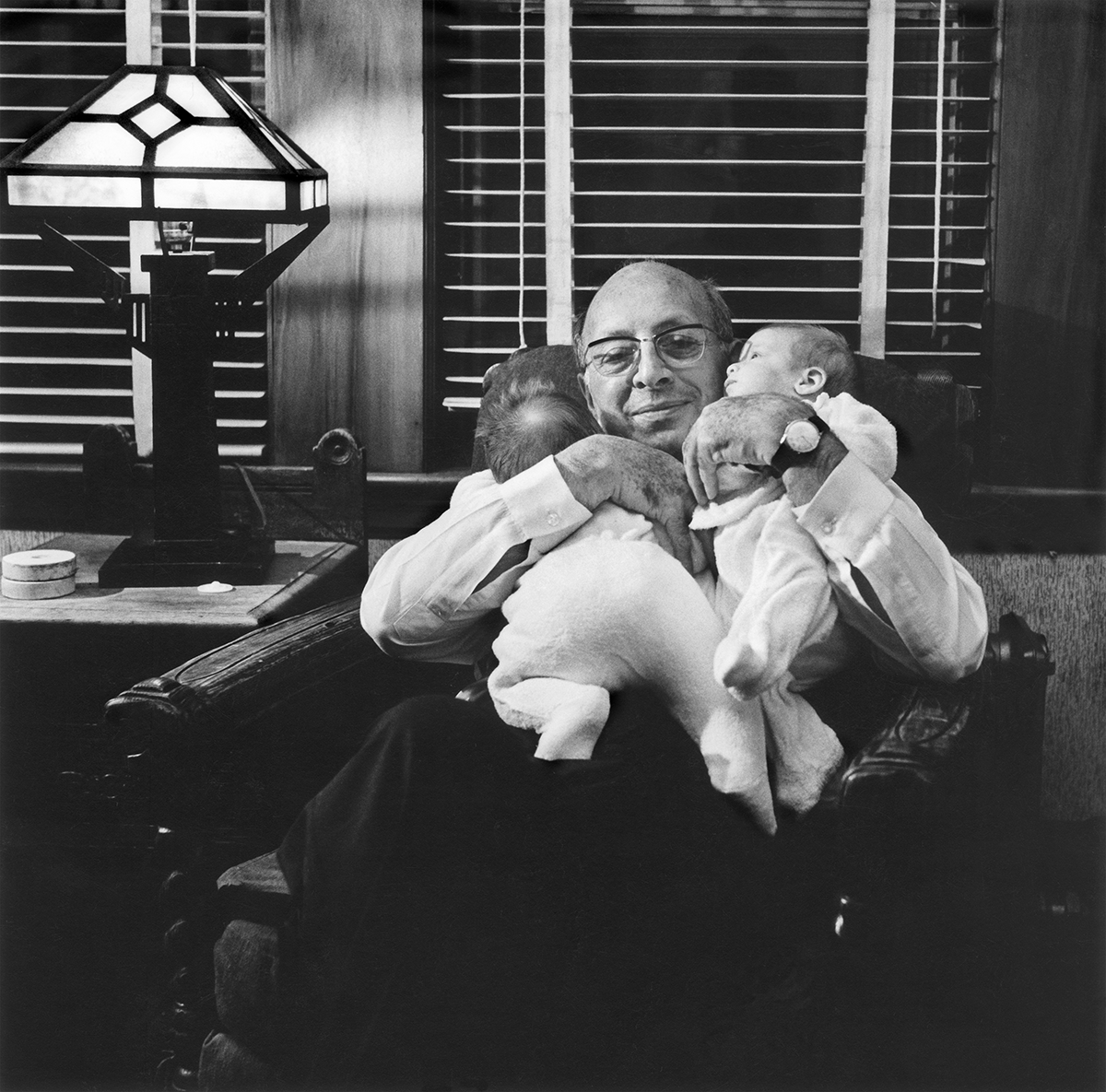

GT: It is still rare to see images of men made by women and even more rare to see them in vulnerable positions. Can you speak to the presence of men in your work?

JL: I’ve photographed male partners and family members nude, in the shower, shaving, in bed, asleep, and with children because each moment was a crucial part of my central project to capture the daily life around me. If my photographs of men stand out, perhaps it’s because the general expectation is to see men in public and powerful roles…not in more private realms.

GT: What do you think your influence has been on the field of photography?

JL: I hope it would be for [making] images of things, places, and people from women’s realms and private spaces—from a woman’s own perspective. But a large body of my work is in photo collage, made with the goal of juxtaposing the intimate with social questions or political issues that are circulating today in the world. I would happily be known for distinguished photo collage work as well.