***Editor’s Note: A shortened version of this article is printed in the Fall 2010 issue of Women in the Arts magazine. The article is based on letters in the Nelleke Nix and Marianne Huber Collection: The Frida Kahlo Papers, donated to NMWA in 2007.

Letters, like diaries, constitute a very particular genre. It is usually thought that correspondence is quite personal, and that correspondents reveal themselves in their letters, possibly exposing aspects of themselves that would otherwise remain hidden. Letters may therefore serve as a foil to the public persona, which may or may not coincide with the private one. But, as Louis Menand suggests, there is no reason to assume that letters and diaries are more authentic than other written media or ways of presenting oneself to others.[i] After all, no penalty accrues to those who lie, exaggerate, or selectively choose what to include in a letter or diary. Moreover, correspondence can serve a variety of purposes, including transmitting gossip, venting, settling accounts, and confessing, sometimes expressing fleeting sentiments that nevertheless remain captured on paper for posterity.

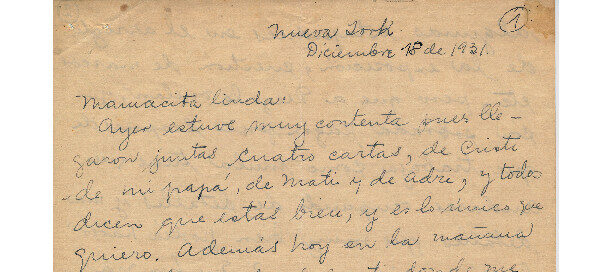

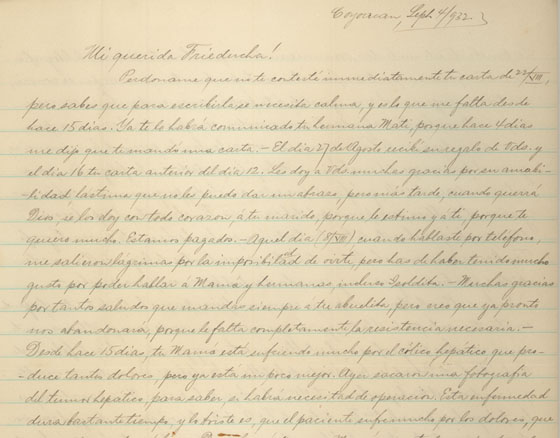

The correspondence between Frida Kahlo and her father, Guillermo Kahlo, is of interest not only because it concerns two figures prominent in Mexico’s cultural history, but also because it can shed light on the personalities of each of the correspondents and on the relationship between them. Here, we refer to those penned by Guillermo Kahlo from 1932 to 1933,[ii] when his daughter was in the United States, reveling in new experiences and leading a life that was very different from the one she had led in Mexico. Although the letters cover a relatively short period of time, these were years of great upheaval for both correspondents.

The letters suggest the trust there was between father and daughter, a relationship that was apparently very different from that between Guillermo and his other daughters. The letters also shed light on Frida’s activities and feelings during a formative period in her life, when she assumed the role of wife of Diego Rivera vis-à-vis his American patrons, the Ford and Rockefeller families, among others; saw the ocean and traveled by airplane for the first time; had to negotiate a new language and adapt to different environments; and began painting not just to pass the time, but with the hope of exhibiting and selling her work. At the personal level, she suffered a miscarriage and the loss of her mother, two events that that left her physically shattered and emotionally distraught. The impact of her mother’s death was exacerbated by the fact that Frida was in Detroit when her mother took ill, requiring Frida to return to Mexico when she was still fragile and recovering from her own medical problems.

For Guillermo, these years were marked primarily by the death of his wife, which left him unhinged and depressed. Although his daughters visited him often and included him in their family outings and activities, Guillermo knew that the comfortable dailiness of his life had changed dramatically. He felt he would never be the same person again, a belief that was self-fulfilling as the loneliness of being a widower accentuated his tendency towards taciturnity and introspection. He had suffered from epilepsy from his youth, and his health issues were now further complicated by loss of hearing in one ear and intestinal problems. In addition, his career as a photographer, which had peaked in 1904–08, when he had been hired by the government of Porfirio Díaz to document Mexico’s architectural patrimony, was now on the wane. Only former clients sought him out, and he did not have enough work to keep him engaged and employed.

Although the letters written by Guillermo Kahlo appear to be fairly complete,[iii] we have none of his daughter’s replies. What should have been a dialogue is therefore more of monologue, or a conversation in which only one of the parties is heard. Nevertheless, Guillermo summarizes the news and alludes to Frida’s comments when answering her letters. As a result, the reader is able to follow the “plot” in the epistolary exchange.

Dramatis Personae: Brief Background

Guillermo Kahlo was born in Germany and did not emigrate to Mexico until age nineteen. Although several books state that his family was Jewish, a provenance that Frida stressed and around which some historians have woven an intricate web,[iv] more recent research has found that Guillermo came from a long line of Lutherans on both his maternal and paternal sides.[v] Although his family was financially comfortable and he was not seeking to make a fortune in the new world, he was in search of a new home and the opportunity to follow a new path. His mother had died, and his father had remarried. Because the young man did not get along well with his stepmother, his father gave him enough money to sail to Mexico, a country which the youth adopted as his own. He changed his name from Wilhelm to Guillermo, learned Spanish, and never again returned to Germany.

In Mexico, Guillermo was able to find employment in different businesses operated by German immigrants. He also married a Mexican woman who died shortly after her second delivery, having given birth to two daughters. When he was twenty-six, Guillermo married again. His wife, Matilde Calderón, encouraged him to take up photography, which was her father’s line of business. This was the field to which Guillermo would devote the rest of his life. According to his business card, his specialty was taking photographs of “landscapes, buildings, interiors.”[vi] By 1904, Guillermo was well settled into his new calling. This allowed him to buy a plot of land and build a house in Coyoacán, then a town outside Mexico City. By that date, he and Matilde had had two daughters, a family that they would complete with the births of Frida in July 1907 and Cristina, a mere eleven months later.

Guillermo Kahlo never lost his German accent, but he learned to write correctly in Spanish. His letters, in contrast to the very spontaneous ones of his daughter, are examples of deliberate thought, careful penmanship, and skilled writing. They reveal a relationship based on affection, respect, and a desire to protect his daughter from the traits and personality flaws that he and his daughter shared. Years later, Frida would describe her father as “interesting, rather elegant in the way he moved, […] calm, hard-working, brave, with few friends.”[vii] As Raquel Tibol has written, it was he who taught his daughter “the ability to overcome physical pain, latching on to life not with complaints, but with facts and products.”[viii]

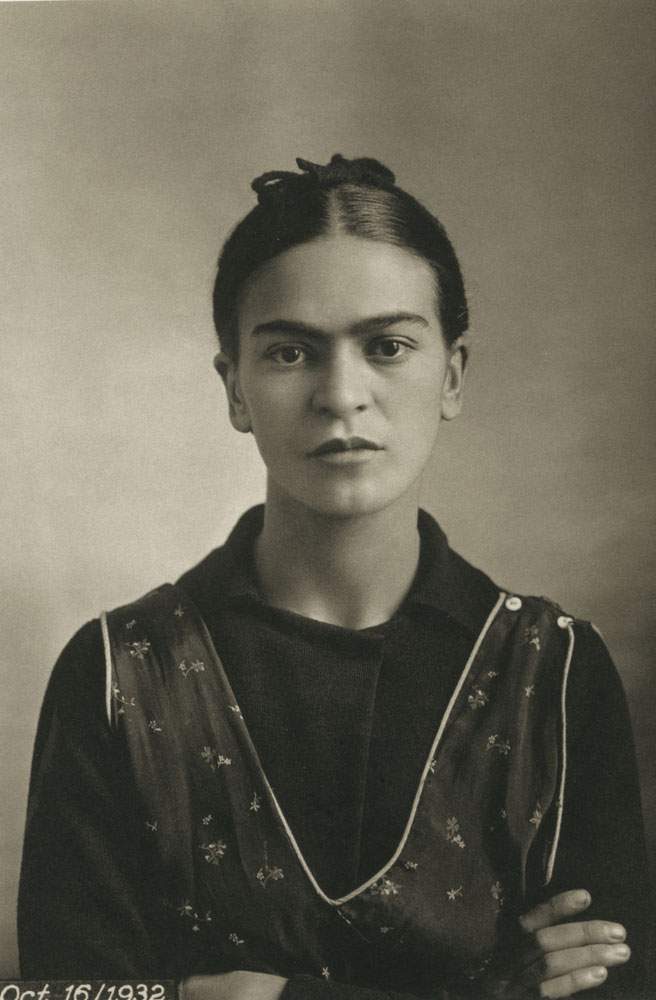

Frida was twenty-four during most of the period captured in the letters. Although she had hardly left Coyoacán and the Federal District prior to 1931, she had had unique experiences that had broadened her world view and given her a certain sophistication. As a student in the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria in Mexico City, Frida (one of only thirty-five females in a student body of two thousand), had joined a group of young intellectuals who called themselves “Las Cachuchas” (“The Hooded Ones,” after the special hats they wore) and who shared the romantic nationalism that was then being promoted by Minister of Education José Vasconcelos.

Two extended convalescences nurtured the close relationship between Frida and her father. The first took place when Frida contracted polio at age six and was house-bound the better part of nine months. The condition left her with a leg that was thinner and slightly shorter than the other. Guillermo devoted himself to her recovery, encouraging her to exercise and practice sports. Always attentive and affectionate towards his daughter, he made sure that Frida would swim and play ball in addition to riding a bicycle and climbing trees.[ix] And Frida would later reciprocate his ministrations, taking care of her father when he suffered epileptic seizures.

The second convalescence, also lengthy, took place when Frida was eighteen. A streetcar accident injured her spinal column and clavicle, and lacerated her hip and her pelvis, serious wounds that would keep Frida hospitalized and bed-bound for many months and would leave emotional and physical scars for the rest of her life. But the long recovery also gave the young woman an opportunity to read, write, and reflect. Equally important, she began to paint, an activity which was nurtured by her father. Her new pastime in turn provided her with a new field in which she could fulfill her talents and ambitions. Even as an amateur, Frida had no misgivings about seeking out the advice of Diego Rivera, twenty years her senior and well-established as a muralist of original and impressive frescos, concerning her potential in the world of art. The encounter would eventually lead to a romantic relationship and marriage.

As Diego Rivera’s wife, Frida had unusual entry into the political, intellectual and artistic life of Mexico in 1929, when the world economy was on the verge of crumbling but the Mexican muralists were gaining increasing recognition on the international scene. By that date, Rivera had already received important commissions, and was about to leave for the United States, where he would paint frescos in San Francisco, Detroit, and New York. Frida accompanied him on these trips but was in close contact with her family through the many letters that traveled back and forth between the United States and Mexico.

The letters of Guillermo Kahlo to his daughter are not only a chronicle of his activities and the afflictions of the extended Kahlo family, but also a touching expression of paternal love. Two themes are recurring motifs: (1) his desire to spare Frida some of the problems that beset him (2) his descriptions of what he perceives to be his physical and psychological decline. At the same time, the letters capture some of the ideas proposed by Frida to lift her father’s depression, as well as his reactions to her suggestions.

Epistolary Hugs

Guillermo Kahlo was known for his strong personality, often attributed to his Teutonic culture; his daughters mocked his irate temperament, nicknaming him “Herr Kahlo.” The letters, however, show another facet of his personality: he was an affectionate and expressive father who did not hesitate to launch a scathing criticism when he considered it justified. The letters are sprinkled with many examples of his love. Even in the salutations, he addresses his daughter effusively, using the original German spelling of her name and calling her “My dear Frieda!”, “Dear Frieducha!”, “Dearest Frieducha!”, “Beautiful Frieduchita of my heart!”, “Adored Frieducha.” Repeatedly, the writer expresses his sadness over Frida’s absence, as well as his desire for her safe and prompt return:

Oh, Frieducha, every time I read your letter, I shed tears of sadness over two persons, because I am unable to show the letter to one of them because she left for good and is underground, and because the other is above ground but is frighteningly far away and I have no guarantee of seeing her again. (December 2, 1932)

Respect God above all, because he reigns over everything (even when many say otherwise), then your husband, because he is good to you and deserves it, and thirdly, remember sometimes, when your thoughts wander, that in the Federal District you have people who adore you, including the one who signs this letter! (February 5, 1933)

Remember, Frieducha, that every time I receive one of your letters, I am very pleased at the same time that I get sad, please do not forget that. (April 21, 1933)

Last night I learned that you will not come back to Mexico until your husband has finished his work. On the one hand, I am pleased that you are always with him. But I am also sorry that the pleasure of giving my Frieducha a hug and a kiss will not happen for a long time still. (August 8, 1932)

Paternal Advice

Despite considering Frida energetic and feisty, Guillermo Kahlo worried about her, because he also perceived her as fragile and helpless. In addition, he felt she had inherited his character and what he called the “Kahlo stubbornness.” He therefore sensed that his own life experiences and what he had learned during his sixty-plus years would be useful for her. When Frida wrote that she would travel from Detroit to Mexico during her mother’s illness, her father informed her that he would remain uneasy, “not because of your arrival, but because of any mishap that may occur during the trip, without having anyone to take care of you.” (June 30, 1932)

Commenting on the end of a streetcar strike that left the inhabitants of the capital without transportation, Guillermo pointed out that, although he had not read the newspapers and therefore did not know who had prevailed during the conflict, it would “probably be the company and not the poor workers. You know how wicked humanity is!” This exclamation is then followed by the following comment: “I advise you to deal with others as little as possible. Get along well with your husband, and laugh off the rest, or treat them with indifference. You will therefore have neither friends nor enemies, and will be at peace with yourself.” (August 8, 1932) He also gives her the following advice:

If you think that you have inherited from me a dislike for people and a desire to deal with others as little as possible, you may be right. But I can assure you, from all my heart and experience, that with that you have gained a lot. You will not have so-called friends, because they tend to dupe you, but neither will you have enemies. I don’t know which is of the two is more valuable. (February 5, 1933)

[…] the best thing is not to interfere with people, although at times there is no alternative, and it is the stomach or the head that suffers. (February 5, 1933)

At the same time that he was proffering his comments, Guillermo was aware that his advice would not be heeded, because Frida had a mind of her own and could be domineering. He therefore writes her the following:

Much time has to elapse before we can know someone well. At times I doubt that you and I understand each other in depth, after 24 years! (August 29, 1933)

It’s a pity that you did not become an orator, not to say a dictator, because you have the ability, and after I have read your letters, I become a submissive dog, at least for a while, because then my stubbornness takes over […] (August 29, 1933)

Before Frida knew she was pregnant, when she was feeling very ill, her family was very concerned with her health. Her father reiterated his daughter Mati’s advice, who counseled Frida to “do everything the Dr. tells you. Be good and obedient so that our minds can be at rest.” Some two weeks later, Guillermo underscores the following:

In your letter you say that I should not worry about you because your health is all right. Don’t be such a liar, Frieda, because I know very well that you are still sick. I can only pray to God to relieve your pain, even if it is little by little, but surely, because your illness is not the kind that will disappear from one day to the next. (December 21, 1932)

Complaints and consolation

Even when Guillermo shows himself to be a concerned father worried about his daughter’s wellbeing, he also uses his letters to share his own woes and afflictions. The letters to Frida therefore become a way for him to share his grief and communicate the loss of his will to live. As result, even his chronicle of family activities is interspersed with reports of his multiple ailments. Guillermo often alludes to his declining health, as well as his mourning, his sadness, and his feelings of loneliness:

Now, the one who is in the worst shape is the signer of his letter. In addition to dealing with his physical illnesses, such as anxiety, constant inflammation of the throat, a ringing in the ears and therefore virtual deafness, and an occasional inability to talk, last Saturday he suffered a misfortune [the loss of a photographic lens] that he could have very well prevented, if he had not been so stubborn. (June 30, 1932)

Oh, Frieducha, how much longer will I have to face others wearing a fake expression, when my soul is in constant turmoil. (April 2, 1933)

[…] it would not be bad for the final voyage to happen soon, because it is time for me to be taken away […] moreover, I am more than eager for it to take place, which is the main thing. I no longer harbor any illusions […] perhaps because they know that I no longer have any use for them, why should they fool me? Sometimes I begin to laugh […] but that laughter is a sham! Only tears are real, even when they are hidden, because in public one would look ridiculous. (April 21, 1933)

My tombstone will probably have an engraving saying: In memory of an unhinged person, who could have achieved “marvelous things” if he had not been so stubborn […] (April 21, 1933)

Given how prevalent these sentiments are in Guillermo’s letters, it is not surprising that Frida attempted to find activities to distract her father. Besides requesting copies of photographs he had taken, Frida asked him to take photographs of the house that she and Diego Rivera were building in the San Angel neighborhood, in the Federal District. The house, which was designed by architect Juan O’Gorman, combined the straight lines of Le Corbusier and the functionalism of the German Bauhaus with touches of Mexican vernacular architecture. Reflecting its owners, the house combined two separate residences of unequal size, “the big one painted in a reddish tone, the smaller one pale blue.”[xi] Guillermo keeps Frida informed about the construction, and sends her photographs taken with a panoramic 135 degree lens, which allowed him to “get both facades together, without any trees.”[xii]

Frida was also interested in getting her father involved in a project which would result in a book. She suggested that Guillermo draft a series of pointers on photography, so that his life’s work and experiences would be passed on. But he quickly vetoed that idea, with the following comment:

How do you want me to write a sort of book, when I feel it’s a triumph to pen a simple letter. Each task requires a talent; I have a talent for reading and not understanding the content of a book, but not for writing one. Furthermore, so many books have been written already that undoubtedly there are more than enough for them to be used as toilet paper, and you would not want my work to be put to that use (February 5, 1933, NMWA).

A Poison Pen

As the above suggests, Guillermo’s tendency to focus on his sadness and afflictions does not mean that he lacked a sense of humor. His letters show his wit and critical eye, for which he and his relatives were common targets. Because two of his daughters (Mati and Adriana) were both overweight and garrulous, Guillermo writes Frida the following:

Both Mati and Adriana should cede you part of their volume, which is increasing and will burst. It’s a pity that the words that leave their mouth cannot be applied to the diminution of their bodies’ circumference! (June 14, 1933)

These daughters had married very different men: one of the husbands was very talkative; the other hardly opened his mouth. Guillermo thus describes his sons-in-law:

Two days ago Adriana invited us to dinner, and for 1½ hours I had the pleasure of hearing the record-player, which was on my left (where I have some hearing). I could not clearly make out the words that Veraza [a son-in-law] sent into the air, but I had the pleasure of hearing a constant sound that was not interrupted even when its source was chewing. Adriana joined Mati in trying to outdo him, because they also chatter like magpies, but he still emerged the winner. I don’t know if he was talking about astronomy, mathematics, or philosophy […] (December 2, 1932)

Guillermo also pokes fun at his own behavior, pointing out what he sees as his flaws and stupidities:

[After describing the loss of a photographic lens] If up to now you have doubted that I am dumb, with this description of what happened to me, you will be convinced that I am indeed so! All you have to do is look at my facial features. In comparison with your mother’s face, which turned out very well, I have the expression of an idiot! (June 30, 1932)

I hope that next time I will be in a better mood, but today not even I can stand myself! (June 30, 1932)

When he tries to paint, he is constantly frustrated:

Now that I once again try to dabble somewhat in art, I get a sudden urge to slap myself, because, you know: It is not the same thing to have paint, brushes, etc. etc. and the ability to copy a painting that you have in front of you, than to have, in the first place, the talent to invent an image and then send it from the brain to the hands and through brushes on to canvas […] I am very dumb, and that is why I suffer from bilious tempers and much sadness. (February 5, 1933)

[…] when I am within my own four walls, working on exposing or copying [photographs], I slap myself because of the many stupid things that I have done and continue to do. But now the only result is the confirmation that I have been very dumb for most of my life! (June 14, 1933)

Despite his many expressions of affection for Frida, Guillermo does not spare her from his epistolary barbs. His criticism must have been particularly wounding, because it was aimed at the occupation in which she aspired to make her mark: painting. Any censure in this area must therefore have had a deep effect on her self-esteem. In consecutive letters, Guillermo writes Frida the following:

I thought that you’d never write to me again because f my scolding concerning your art work, but I see that, in spite of everything, you love me. (August 17, 1933)

The main thing is […] that you are fully recovered from your foot injury, so that you’d be able to walk to Mexico if anything happened to the trains. It would not be a bad idea for you to figure out (but correctly, not like your painting) how long it would take to make the trip from New York to Mexico’s Federal District, solely on foot. (August 29, 1933)

We do not have a copy of the letter to which Guillermo alludes in the first of these two missives, nor do we know what painting he was referring to in his criticism. But by that date Frida had already completed some of the works for which she would later attain worldwide recognition.[xiii] She had focused on self-portraits, although with inconsistent results. Both the tone of the criticism and the chronology suggest that Guillermo was referring to a 1933 self-portrait to which Frida later added self-accusatory remarks around the painting of her head. These graffiti include the following comments: “Oh! Boy,” “No good,” “Very ugly”.[xiv] Nevertheless, there is the ironic possibility that “Herr Kahlo” was referring to another self-portrait of the same period. This, titled Self-portrait with Necklace (1933), has become one of the most iconic and widely reproduced images of Frida, having been used in postage stamps both in Mexico and in the United States.[xv]

Historical Postscript

Despite her father’s harsh judgment—or perhaps because of it—Frida continued to advance her artistic career. And she not only received the approval and support of her husband, but also that of Pablo Picasso and French surrealist André Breton. During Guillermo’s lifetime, Frida’s work was exhibited in New York and Paris, although not in Mexico. While she did not have great expectations concerning her career, and stated that “I continue to dabble in paint. I paint little, but I feel that I am learning something,”[xvi] painting was more than her occupation; it was her calling.

Although Guillermo was eager for the “final voyage” (i.e., death) following the loss of his wife, he would survive her by nine years. When he died of a heart attack in 1941, his favorite daughter was devastated. Writing to her medical advisor and good friend Dr. Leo Eloesser, Frida stated the following: “My father’s death has been something awful for me. I think that is why I have gone very much downhill and lost a lot of weight once more. Do you remember how handsome and how good he was?”[xvii]

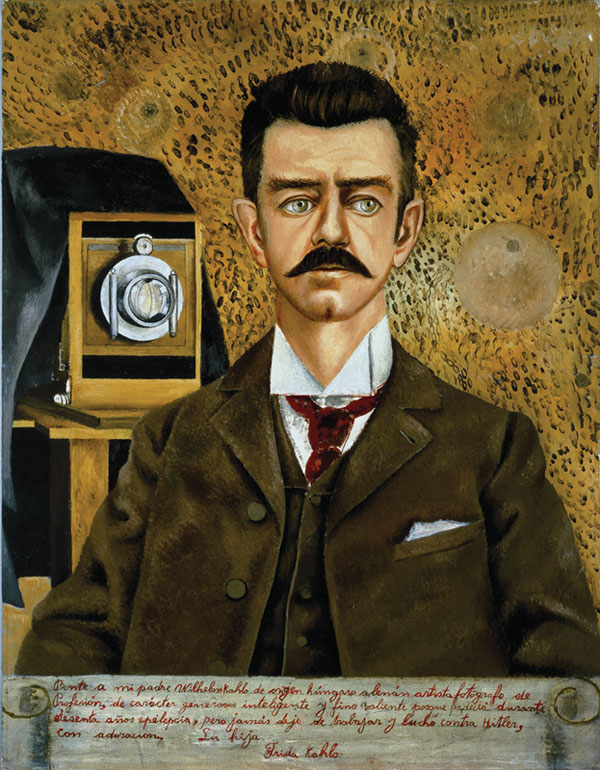

It would take Frida ten years to honor the memory of her father in the manner most appropriate for her: in an oil portrait. In this Guillermo appears looking sideways, accompanied by the photographic equipment that was so much a part of his life. As in the traditional ex votos, the painting includes a written garland with the following explanation: “I painted my father Wilhelm Kahlo, of Hungarian-German origin, professional artist/photographer, whose nature was generous, intelligent, and polite. He was courageous, having suffered from epilepsy for sixty years, but he never stopped working and he fought against Hitler.[xviii] Adoringly, his daughter Frida.”

Most likely Guillermo Kahlo never expected to his portrait to “speak from the walls,” nor did he believe that he would be immortalized through this medium. He could also have never predicted that his daughter would reach the heights of artistic recognition, being lionized after her death and having her work exhibited internationally. But as “Fridomania” has spread throughout the world, the legacy of both Kahlos has been enhanced. In recent years, the work of Guillermo Kahlo has found a new audience, and his photographs have been the subject of exhibits and books. His photographs of churches have been gathered in a special volume,[xix] and his architectural work has been the subject of a calendar published by a private foundation.[xx] He has therefore entered the pantheon of Mexico’s cultural heroes. And we have added to the reassessment of the man and his work, underlining his niche as the writer of a unique set of letters to his daughter.