Dynamic women designers and artists from the mid-20th century and today create innovative designs, maintain craft traditions, and incorporate new aesthetics into fine art in Pathmakers: Women in Art, Craft, and Design, Midcentury and Today, now on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Each week, compare and draw parallels between works on view in Pathmakers and NMWA collection favorites.

On view in Pathmakers

Eva Zeisel (manufactured by Manifattura Mancioli), Belly Button Room Divider Prototype, 1957

Eva Zeisel is one of the best-known designers of the post–World War II era. Imbuing industrial products with a sensual and organic appearance, Zeisel won wide acclaim for her abstracted ceramic designs. Few people knew that Zeisel had been falsely accused of conspiring to assassinate Stalin, was imprisoned in Moscow in 1936, and later fled Nazi-occupied Austria. After her imprisonment, most of which she spent in solitary confinement, Zeisel said, “I hadn’t seen any colors in over a year and a half.” Her works after this period, including her work in Pathmakers, are often characterized by graceful, vibrantly colored designs with a sense of humor.

Who made it?

Hungarian-born designer Eva Zeisel (1906–2011) is the only woman whose works appear in both the midcentury and contemporary sections of Pathmakers. With an unprecedented 87-year-long career, Zeisel designed ceramics in Hungary, Germany, and the Soviet Union before moving to the U.S. in 1938. She was the first artist to have a one-woman show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1946. She worked well past the age of 100.

How was it made?

Zeisel became known for her furniture, rugs, tiles, and ornamental objects but revealed “ceramics is my favorite, because I can feel it with my hands.” Designed for Manifattura Mancioli in 1958, Belly Button Room Divider consists of double-ended porcelain vessels with slight “belly button” depressions. Rebelling against the straight-line aesthetic of Modernism, Zeisel threaded her ceramic forms into long rows, creating sensual S-curves. Zeisel explained, “the inspiration for my work has been the human body—belly buttons, which I used quite often—nature, and the Hungarian folk art of my youth.” With candy-colored glazes and a sense of playfulness, her work in Pathmakers exemplifies Zeisel’s design goal “to be very friendly.”

Collection connection

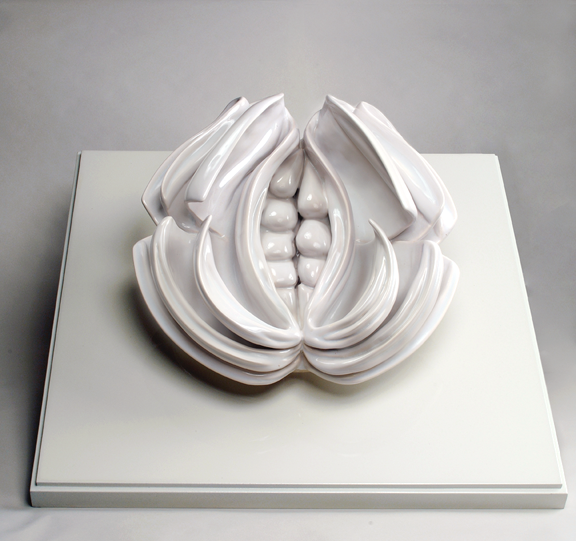

In NMWA’s collection, Judy Chicago’s Test Plate for Virginia Woolf (1978) is also a glazed, porcelain prototype. Chicago created the test plate in preparation for her large installation The Dinner Party. On view in a permanent installation at the Brooklyn Museum, The Dinner Party is one of the best-known works of the 1970s feminist movement, comprising three tables with place settings for 39 prominent women in history.

The test plate has the same dimensions as the final place setting. Each plate is unique to the woman it represents, but they share similar butterfly and vulvar forms. The floral imagery of Woolf’s plate—particularly its seed-like core and petals—may represent the fruitfulness of Woolf’s writing career. The curled petals also evoke an open book’s pages.

Visit the museum and explore Pathmakers, on view through February 28, 2016.