Despite everything we learned in school about sticks and stones, language has an immense impact on the world. Words transform perceptions, and once words are spoken they can continue to inform our thinking whether they are true or not. In her 1989 painting Untitled (141,257), Jane Hammond employs this transformative effect to demonstrate the ways in which words can negatively impact women artists before anyone even sees their actual work.

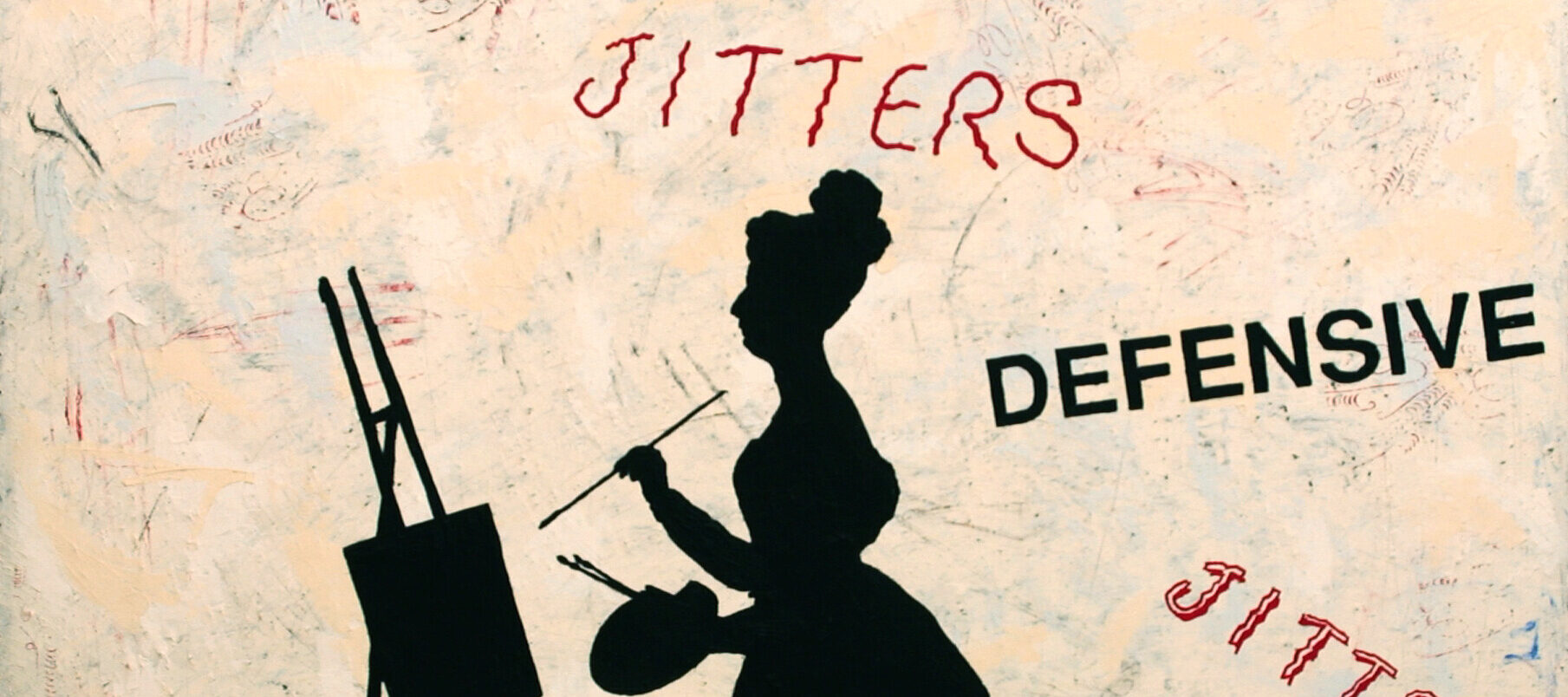

Hammond, a self-described conceptual artist, has demonstrated throughout her career a fascination with the ways in which recognizable images shape our understanding of the world. She culls these images, which include superheroes, celebrities, and miscellaneous household objects, from postcards and pulp literature that she finds at garages sales and flea markets.¹ The center of Untitled (141,257) contains an example of that frequently appearing stock imagery, a familiar silhouette of a Victorian woman painting. However, what makes painting distinct in her oeuvre is the bold inclusion of language. Two words are repeated several times across the picture plane in boldface capital letters: “defensive” and “jitters.” These words form a loose frame around the woman, who is something of a cliché with her easel, brushes, and palette.

However, despite what she holds and what she is doing, viewers cannot solely see this woman as an artist. As a result of the proximity and visual intensity of the printed words that surround her, we cannot help but associate the depicted artist with the jitters and defensiveness. Due to their official-looking font and imposing black and red coloring, the words become like labels, informing the viewer what is before them. Whether we like it or not, these labels state that she is a defensive, jittery artist.

Two questions remain: Is she really defensive and jittery? And what kind of artist is she? Those questions will remain unanswered and her true identity will remain hidden, as the silhouette prevents the viewer from seeing what she or her work really looks like. But perhaps if we could see her face, we could note her calm demeanor. Or if we could just see her work, we could see a groundbreaking moment in the history of art. Unfortunately, there is no legitimate evaluative process that can take place here. All we have is the barrier of words.

As the feminist art collective Pussy Galore have shown us with their recent update of the Guerrilla Girls’ iconic 1986 report card, New York’s blue-chip galleries are far more likely to represent male artists than female artists, despite the fact that women make up the majority of practicing artists today. Untitled (141,257) speaks to the impact that reality has on women artists. If only we could see their work and evaluate it without preconceived labels, perhaps then we could see the full picture.

Note:

1. Douglas Dreishpoon, “Interview with Jane Hammond,” in Jane Hammond: Paper Works, exh. cat., ed. Marianne Doezema (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007), 30.