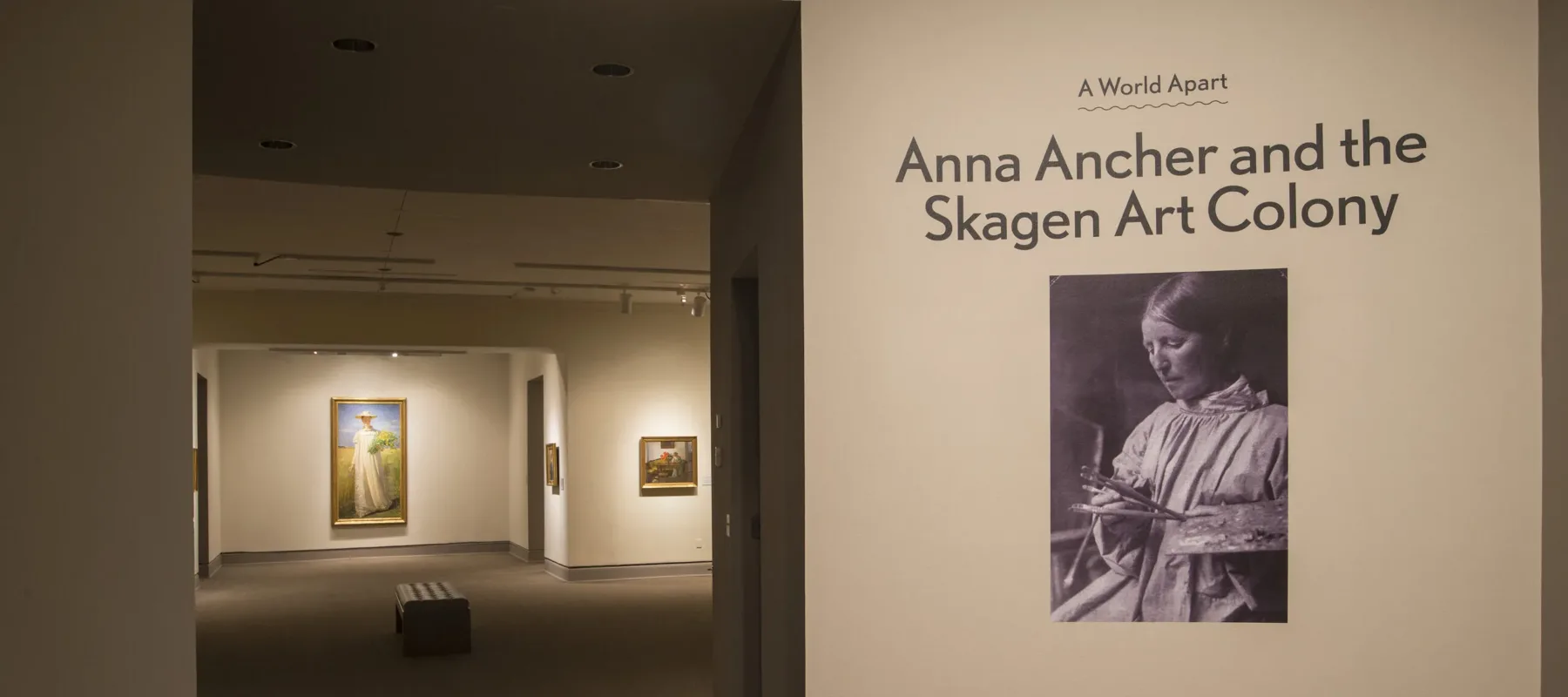

In honor of A World Apart: Anna Ancher and the Skagen Art Colony, we’re researching other delightful, innovative, and interesting Danish women in the arts. Seeking success (and stirring up controversy) a generation before Anna Ancher was the Danish painter Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann (1819–1881).

A Polish-born Danish painter, Elisabeth was trained at the leading Dusseldorf Academy in Germany. She moved to Rome, where she met her husband sculptor Jens Adolf Jerichau. In 1849, her husband became a professor at the Academy and the couple moved to Copenhagen, where Elisabeth struggled to find acceptance within Danish art circles. As a woman artist, she was a rarity at the time, and her German heritage made her unpopular. Ultimately, she managed to appeal to Danish national identity in Danmark. Her triumphant painting personifies the country as a heroic woman and commemorates its victory over Germany in the First Schleswig War (1848–50).

Jerichau-Baumann’s accomplishments, both at home and abroad, gave her validation as an artist. She attracted attention as a portraitist for Danish royalty, but her big break occurred in 1866, when the Danish National Gallery purchased and exhibited her genre painting A Wounded Danish Soldier. In London, Queen Victoria even requested a private presentation of her works, including her 1850 portrait of Hans Christian Andersen. As a friend of the iconic author, Jerichau-Baumann painted him several times. Mermaids and the Grimm brothers are also among the fantastical themes of her paintings.

Enthralled with the “exotic,” she trekked throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East in the 1870s. It seems she could not be confined to any one subject, or nation. Adept at networking, she was granted rare access to paint at several harems in Constantinople. However, she often had to resist rendering her models in the way Europeans imagined because they too wore cutting-edge Parisian fashions. Her works from this period, often characterized by sensual subjects and golden hues, were considered controversial, and many were kept in museum storage rooms in Denmark until recently.

Traveling frequently and forging a career in a male-dominated field, the astounding Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann also gave birth to nine children in her lifetime. Like the fairy tales and dramatic histories that inspired her, the story of this risk-taking Danish dame is truly spectacular.