One of the most influential contemporary photographers of Latin America, Graciela Iturbide has produced majestic and powerful images of her native Mexico for the past 50 years. Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico is the artist’s most extensive U.S. exhibition in more than two decades, comprising 140 black-and-white prints that reveal the artist’s own journey to understand her homeland and the world.

The Seri are an indigenous group that lives in the Sonoran Desert of northwestern Mexico, along the Gulf of California near the U.S.–Mexico border. In 1979, with anthropologist Luis Barjau, Graciela Iturbide (b. 1942) stayed with the Seri community for more than two months, recording their lives with her camera—particularly their forced adaptation to modern life, which began in the 1940s.

Commissioned by the Mexican government, the project was initially designed to document the once-nomadic indigenous population. Yet Iturbide’s works extend beyond documentation: embracing an empathetic approach to photography, she seeks to see and learn through her subjects’ eyes. “I lived with them in their homes, so they would see me always with my camera and know that I am a photographer. In this way, we were able to become partners,” Iturbide said.

Iturbide’s time with the Seri culminated in a book, Los que viven en la arena (Those Who Live in the Sand). According to the artist, she had selected the photographs and the book was all laid out when fellow photographer and book editor Pablo Ortiz Monasterio noticed on her contact sheets the image of an ethereal woman seeming to fall into infinite space. This “discovery” would become one of Iturbide’s most famous photographs, Mujer ángel (Angel Woman) (1979).

This photograph presents a seemingly contradictory image. A woman in traditional Seri dress walks down to the empty desert plain holding her boom-box, a reminder of the technological and material influence of the United States on her indigenous culture. The title transforms the figure into a celestial being: we cannot see her face, and she appears to be floating into another realm, arms spread and hair blowing in the wind.

Other photographs highlight daily life, the landscape, and Seri customs. In Saguaro, Sonoran Desert (1979), a large cactus becomes a pedestal for a flock of black crows; in the distance, the dry desert landscape unfolds. With no people in the photo, and no markers of the encroachment of the modern world, viewers may be left to consider this harsh climate that the Seri people call home and nature’s dominance.

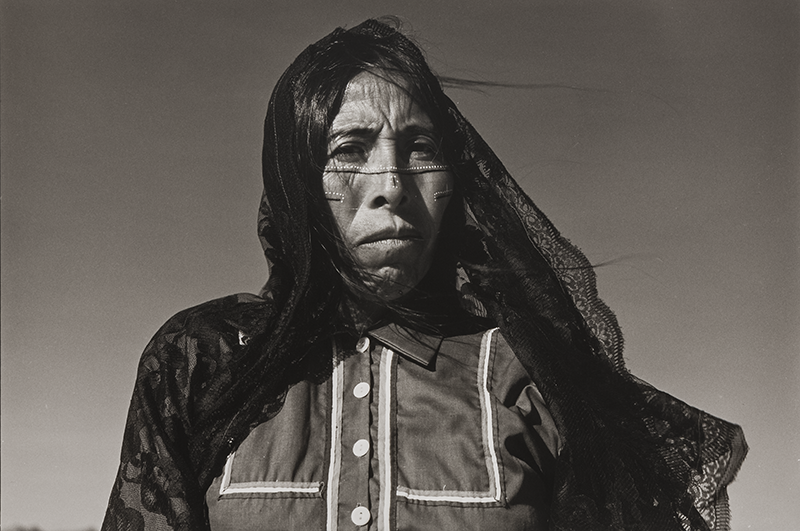

In both Angelita (1979) and Autoretrato como Seri (Self-Portrait as Seri) (1979), Iturbide shows traditional Seri face painting—on both a Seri woman and herself, an outsider. This was a sign of Iturbide’s acceptance into the community, as the Seri women asked to paint her face as they did their own. Iturbide does not exoticize or mimic the practice. Instead, this self-portrait represents her own self-interrogation and integration with her role as a photographer in the indigenous community.

*Unless otherwise noted, information is adapted from Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico: Photographs, by Kristen Gresh, with an essay by Guillermo Sheridan.