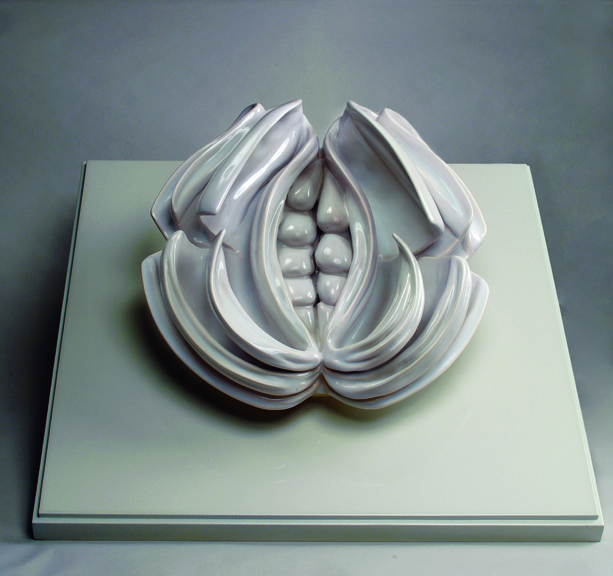

Judy Chicago’s installation The Dinner Party premiered in San Francisco on March 1979. Soon after, it received backlash from the public because the recurring “butterfly” motif in Chicago’s dinner plates was viewed by many to have the appearance of female genitalia. A 1980 People Magazine article on the installation quoted the New York Times chief art critic, Hilton Kramer, describing the installation piece as “vulgar.” Chicago responded to this, saying, “If there is an affirmation of femaleness in my work, what’s wrong with that, given all the phallic imagery around?”

This is not the first time a feminist artist received criticism for depicting images of sexuality in her art. In 1972, Anita Steckel opened her solo exhibition The Feminist Art of Sexual Politics, at the Rockland Community College. Those who were concerned about the school’s public image criticized the artist for her illustrations of male genitalia. In fact, a 1972 New York Post article, “Artist Anita Wins a Battle Over Her Male Nude Show,” illustrated that the complaints drew attention to the double standard in art when it came to sexual representations of the body.

Steckel believed that it was unreasonable for people to consider male representation of female nudes as an acceptable practice in art, when, at the same time, they reject female representation of male nudes.

It is difficult to appease an indecisive public that—within the same decade—could not reach a consensus as to whether what bothers them more is the representation of female or male sexuality. But as Chicago and Steckel have shown in their refusal to censor their works, a feminist artist’s job is less about pleasing the public and more about provoking thought and discussion about issues of gender. As president of the Rockland Community College Dr. Seymour Eskow stated in response to Steckel’s exhibition, “If the purpose of the show was to raise consciousness…it succeeded.” Chicago also suggests that her art’s purpose is to inform rather than censor. She states, “I want to show how women’s experience can be a metaphor for human experience.”

Recently on view in NMWA’s recent exhibition Judy Chicago: Circa ’75, the artist’s Virginia Woolf test plate is a perfect example of her butterfly motif. Additionally, Equal Exposure: Anita Steckel’s Fight Against Censorship, currently on view in NMWA’s Betty Boyd Dettre Library and Research Center, includes some artworks presented in Steckel’s 1972 exhibition, as well as archival documents and articles that surrounded the controversy.