At the National Museum of Women in the Arts, we regularly rotate our collection to spark new thematic connections. This is an essential part of our curatorial philosophy. In a six-post series, I will explore the themes featured in our most recent collection installation. Read about our “Family Matters,” “Rebels with a Cause,” and “Space Explorers” themes, and stay tuned for more.

Awed by nature’s beauty and complexity, generations of women artists have celebrated and interpreted the environment through art. In the 17th century, artists embraced botany and entomology, uniting science and aesthetics in meticulous illustrations of flowers and insects. Whether investigating familiar or far-flung regions, artists have responded to nature as an expression of their desire to expand human knowledge.

As a setting for human activity or a visualization of an artist’s memories and emotions, landscape imagery piques our curiosity and invites subjective responses. Other artists extend their vantage point beyond the horizon, inspired by the cosmos as a means of understanding the universe and our place in it.

Gallery Highlights:

Spider III (1995), a bronze sculpture by modern art legend Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010), proves that natural beauty comes in all forms. Bourgeois, whose mother died when she was 21 years old, associated arachnids with maternal protectiveness. She frequently remarked that her mother shared the admirable attributes of spiders: patience, industriousness, and cleverness.

Abstract Expressionist painter Joan Mitchell (1925–1992) celebrated an often-overlooked element in nature within her exuberant painting Sale Neige (1980). The work’s French title translates to “dirty snow,” alluding to the grit and grime that spoils the pristine white over time. Mitchell associated cold weather with silence and loneliness, yet her vigorous brushwork and blend of black, white, purple, and green pigments communicate an energetic, even joyous quality.

Between 1997 and 2002, photographer Justine Kurland (b. 1969) focused her camera on landscapes as she drove across the United States. In her series “Girl Pictures,” Kurland staged teenage girls in various outdoor settings, creating a dreamlike, dystopian world where they “claim territory outside the margins of family and institutions,” as the artist has said. Her photographs are also on view in NMWA’s exhibition Live Dangerously (September 19–January 20, 2020).

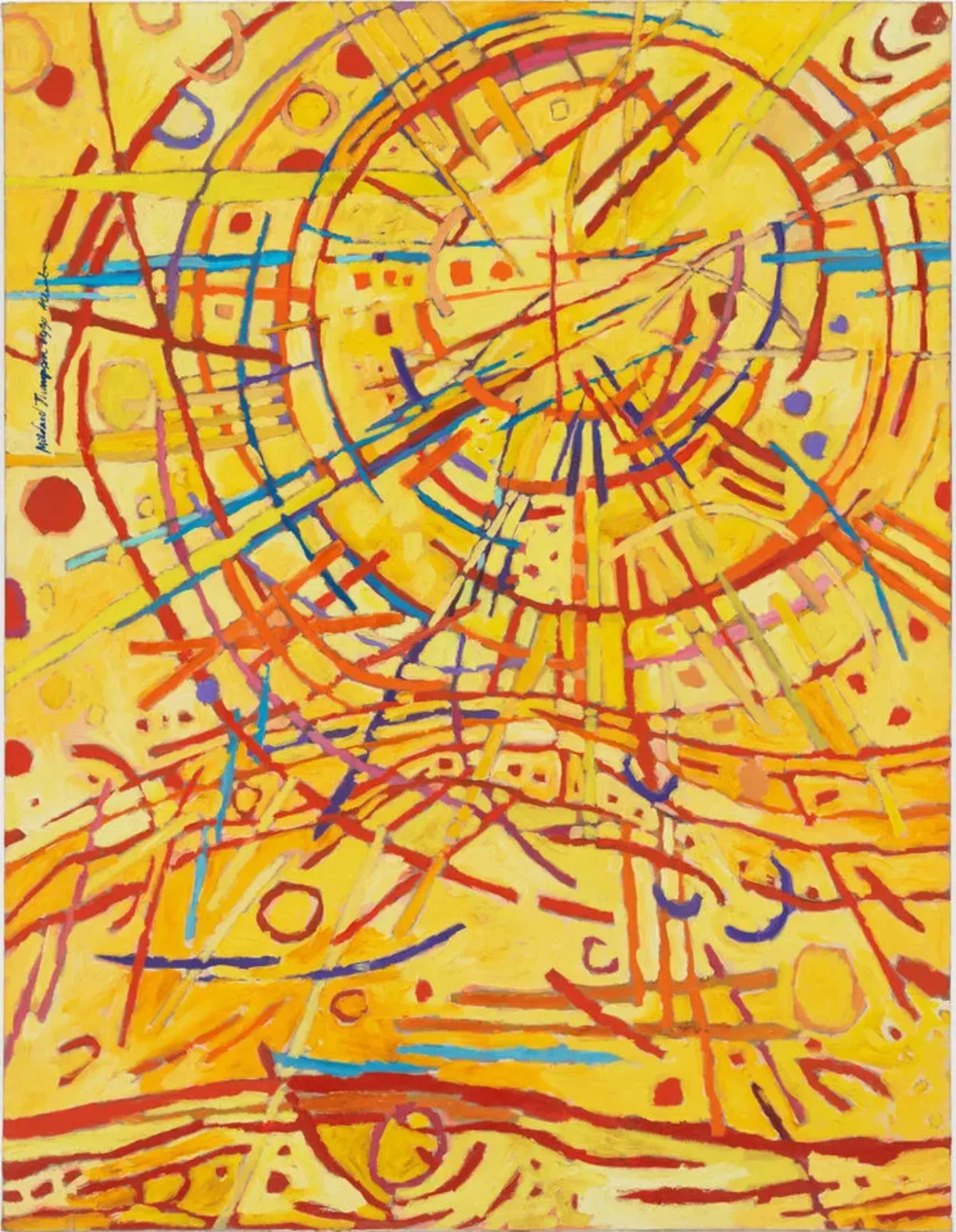

“Magnetic Fields,” a series of intensely colored abstract paintings by Mildred Thompson (1936–2003) convey phenomena not visible to the naked eye, as well as the artist’s personal interest in quantum physics, cosmology, and theosophy. Through her art, Thompson sought to connect scientific knowledge and metaphysical philosophy.

Dutch still-life painter Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750) was renowned during her lifetime. Over centuries, however, she was written out of art history because of her gender. Ruysch created works for an international circle of patrons and served as court painter to the Elector Palatine of Bavaria. With razor-sharp technical accuracy, her floral compositions artfully combine blooms from different seasons, many dotted with insects and spiders. More of Ruysch’s work is featured in NMWA’s exhibition Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age, opening October 11, 2019.