Artist Faith Ringgold (b. 1930) calls upon each of us to tell our stories. During NMWA’s renovation project, we are committed to continuing to share the story—and experience—of American Collection #4: Jo Baker’s Bananas (1997), a quilt by Ringgold in the museum’s collection.

This spring, the New Museum in New York City presents Faith Ringgold: American People, which features Jo Baker’s Bananas as part of a comprehensive assessment of Ringgold’s work across six decades.

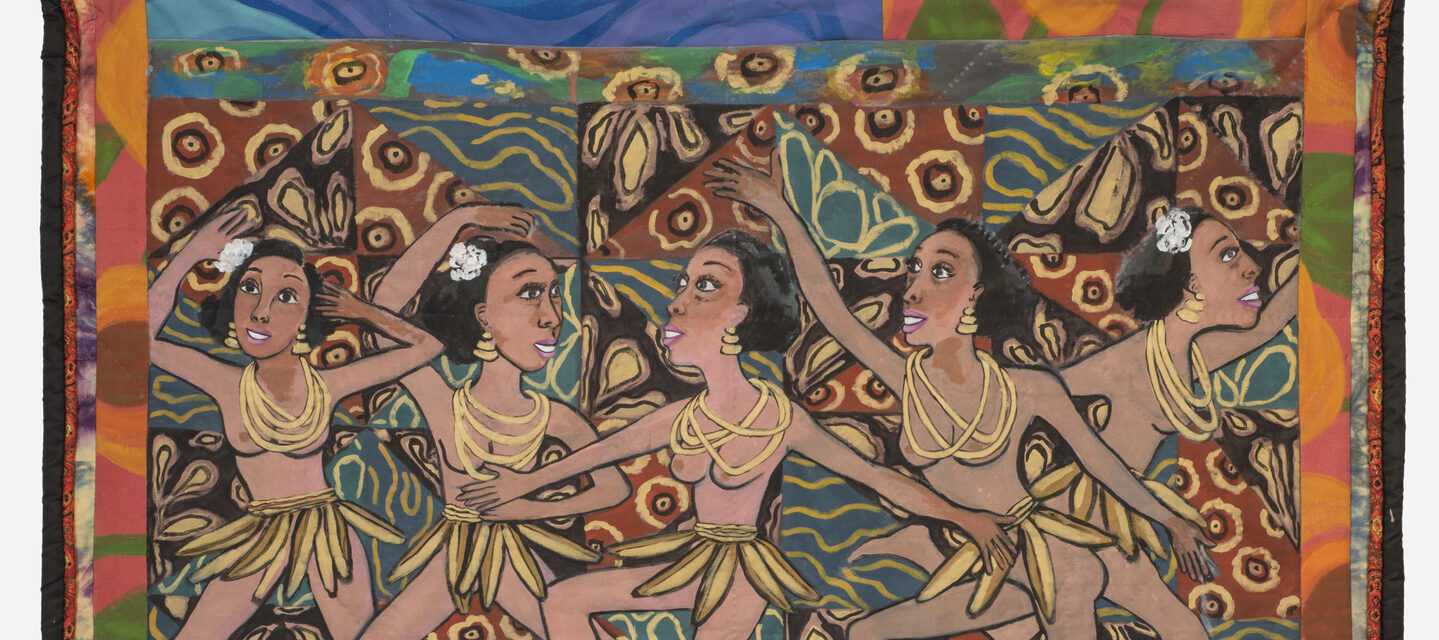

Jo Baker’s Bananas

Acclaimed for her visual art, books, and activism, Ringgold frequently embraces the traditions of quilt-making to depict her personal story as well as interpret narratives from the Black American experience. The artist’s “American Collection” series comprises 12 story quilts that recontextualize symbols like the American flag and the character of Aunt Jemima. Two quilts in the series depict musical performers. Vocalist and dancer Josephine Baker (1906–1975) is the subject of Jo Baker’s Bananas, and blues singer Bessie Smith (1894–1937) features in American Collection #5: Bessie’s Blues (1997; Art Institute of Chicago).

Josephine Baker was born in St. Louis but became a stage legend in France, where she lived most of her life. The so-called “Banana Dance” that Baker performed in 1926 at Paris’s Folies Bergère music hall cemented her fame. Depicting this dance in Jo Baker’s Bananas, Ringgold painted Baker’s figure five times across the top of the quilt, suggesting the movement of the dancer’s body across a stage.

In the early 20th century, Parisians vaunted art and music created by Black artists, yet the audiences’ interest was profoundly shaped by biases about race and sexuality. After the 1920s, Baker succeeded in developing performances that transcended stereotypes about race, becoming an artistic icon as well as an esteemed participant in the French Resistance during World War II.

Baker also used her high profile to call attention to persistent discriminatory practices in her birth country. When she returned to the U.S. to perform in the 1940s and 1950s, she insisted that her audiences be racially integrated. Ringgold references this principle through the varied skin tones of the audience members she painted along the bottom edge of the quilt.

The unique format of Ringgold’s story quilts, with painted canvases stitched into a pieced border, is inspired by both her fashion-designer mother and Tibetan thangkas—paintings on cloth framed with brocade. Ringgold joyfully recalls discovering thangkas during a 1972 visit to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam:

“I wanted to paint big—I had a lot to say. And with no stretcher bars, there was no heaviness. So, if I made it in quilt form, I could pick up a painting that was as big as the room, roll it up, and carry it myself. Before then I had to wait for my husband to get home to move my work, and that was crazy.”

The story of Josephine Baker’s artistry and advocacy— and its amplification in the work of Faith Ringgold—is a vital part of the New Museum’s exhibition exploring Ringgold’s powerful vision. We are delighted to participate in this momentous project.