Conflict zones have historically been male-dominated spaces, for those participating in war and struggle as well as those documenting the events. Photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White and multimedia artist Ambreen Butt offer alternative perspectives to the field’s predominant male viewpoints. Though their work spans different mediums, times, and regions of the world, the two women are united by their incisive interpretations of conflict.

Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971) began her career photographing architecture and documenting the poverty of the Dust Bowl as Life magazine’s first female photojournalist. During World War II, she became the first female war correspondent after initially being denied accreditation to accompany U.S. forces overseas. From the frontlines, she produced matter-of-fact photographs that documented Europe’s war-torn cities and the liberation of concentration camp survivors, among other important events.

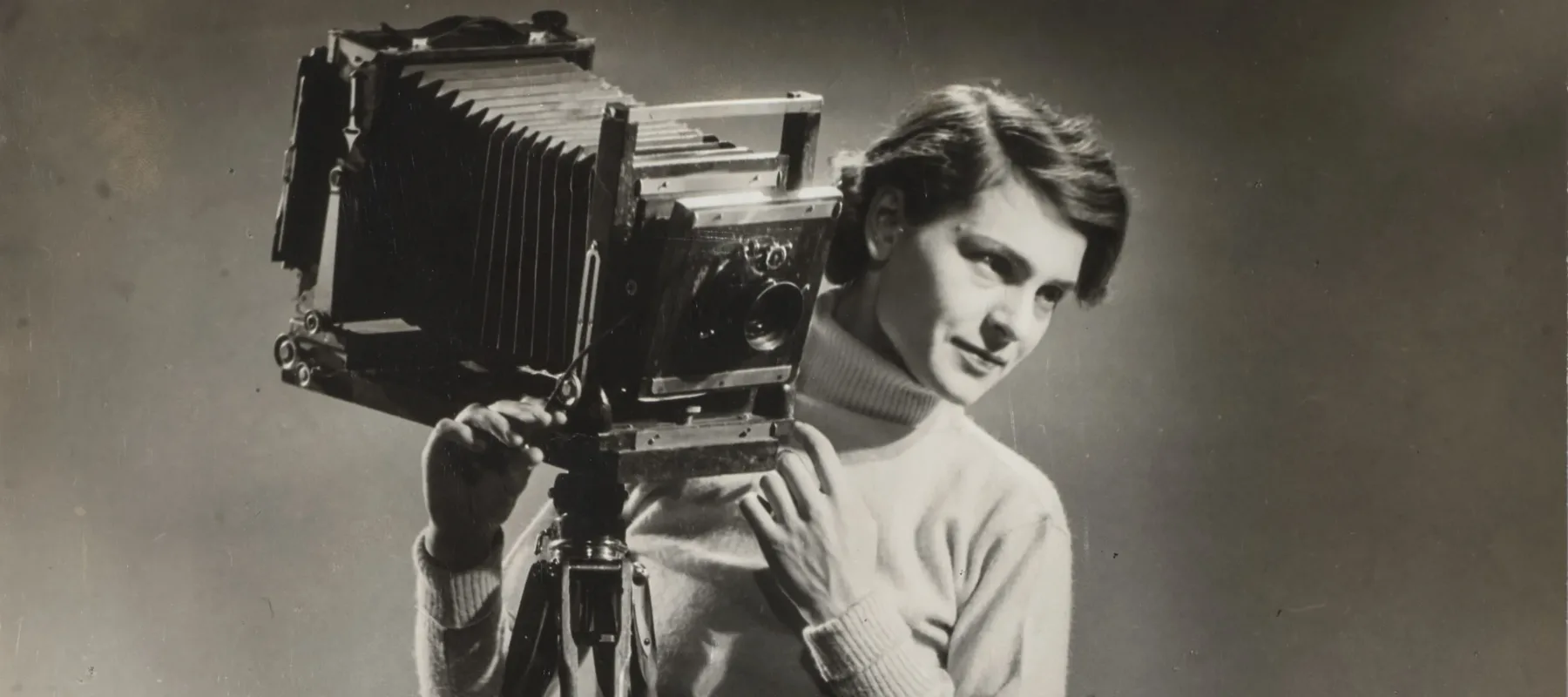

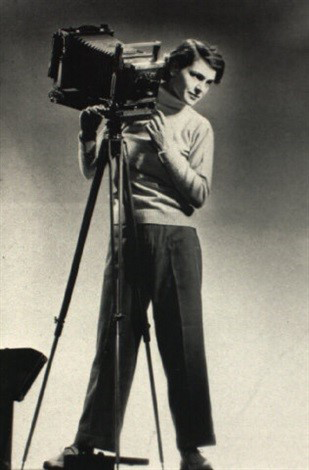

Bourke-White’s self-confidence and conviction—two qualities necessary for the work she was doing—are evident in her own Self-Portrait (1933). Standing next to her camera, she gazes confidently into the distance. Here she presents herself as the subject: a professional photojournalist. Her wide-legged stance and androgynous clothing convey her defiance at being treated like a “girl,” which she often was during missions. Bourke-White crafts a very specific persona for her audience: a fearless, strong woman whose eye does not flinch at war, death, and destruction.

Differing from Bourke-White’s unflinching photographs are the layered and lyrical depictions of conflict from artist Ambreen Butt (b. 1969). Her mixed-media works are rendered in the tradition of Persian and Indian miniature painting, with collaged shredded text and systemic mark-making that show her contemporary art influences. They explore the relationships between beauty, violence, strength, and vulnerability, as Butt methodically layers images and processes her difficult subject matter. In all of her images, heroines—both historical and contemporary—are redefined through the gaze of a female artist.

In the series “Dirty Pretty” (2008), Butt portrays female Pakistani lawyers protesting the government’s suspension of the country’s Chief Justice in 2007. Instead of looking on as passive bystanders, the women demonstrate alongside their male counterparts as intrepid activists. Butt communicates their sorrow and horror—yet, above all, it is their act of resistance that stands out. Their faces are hand-stitched in a prominent red thread over layers of historical imagery, which appear like apparitions in the background.

“My protagonist is not an idealized character; she is a mirror in which a million women see their faces,” Butt has said. This universality is also seen in Bourke-White’s work—her photographs and writings offer her perspective as a woman in a male-dominated society and profession, helping other women to see themselves and their own potential. Butt’s works center around heroines, while Bourke-White becomes a heroine herself. Ultimately, in both of their works, women are portrayed as active witnesses—they claim agency, and they make their marks on society.

Ambreen Butt: Mark My Words was on view at NMWA from December 7, 2018–April 14, 2019.