In Clues in the Calico: A Guide to Identifying and Dating Antique Quilts, Barbara Brackman discusses the ways in which certain characteristics of a quilt can disclose important information on its origins and the time is was made. In addition to dating quilts through their style and patterns, she also dates them in a more scientific way through their dyestuff.

The book talks about two types of dyes: natural dyes and synthetic dyes. Natural dyes are extracted from natural substances such as animals, plants, and minerals, and generally need the help of a substance, called a mordant, that allows the color of the dye to adhere to the actual fabric. On the other hand, synthetic dyes are human-manufactured and came into prominence in last half of the 19th century. At the time, most of them were imported from Germany, which held internationally-honored patents for their dyes. It was not until after World War I (when the German patents were awarded to Americans) that the American dye industry began to thrive.

Brackman illustrates that both natural and early synthetic dyes were difficult to work with. Often, the dyes were not as colorfast as quilters would have liked, and they would slowly begin to fade. This made conservation difficult, especially if the maker intended to pass a quilt on to future generations. To add to this, many types of dye, especially ones with iron or tin mordants, can deteriorate the fabric itself, again causing problems for conservation.

Until the first half of the 19th century, green dye was specifically difficult to both produce and manage. Many quilters had to perform a painstaking double-dyeing process that consisted of first dyeing the fabric yellow and then dyeing it again with indigo or Prussian blue, or vice versa. The final product was a vivid green color many quilters referred to as “poison green.” According to Brackman, single-process synthetic dyes came after 1860 and were able to provide quilters with a much simpler process. However, many of these later synthetic dyes were not as colorfast, especially when exposed to light, and ended up fading to beige.

Although the color of a quilt can play a major role in its aesthetic value, not many people realize how useful the condition of the dye really is to justifying the historical significance of a quilt. Changes in the process of dyeing fabrics and the ingredients used in dyestuff parallel the chemical and technological advancements of the time. These facts can not only help date a quilt, but can also help in informing the quilt’s conservation.

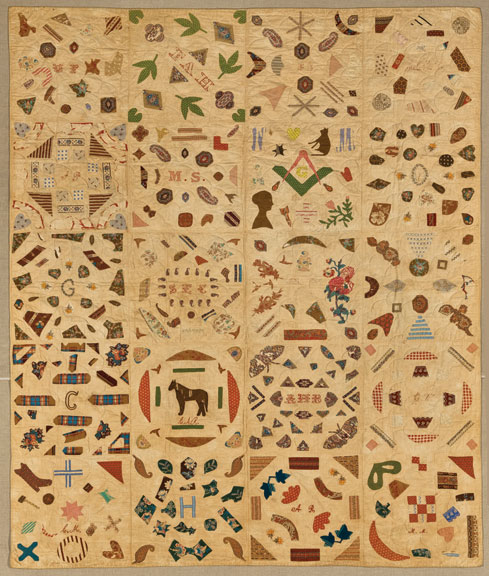

To learn more about quilts, as well as the people who created them and the ways society saw them, visit “Workt by Hand” at NMWA, on view through April 27!