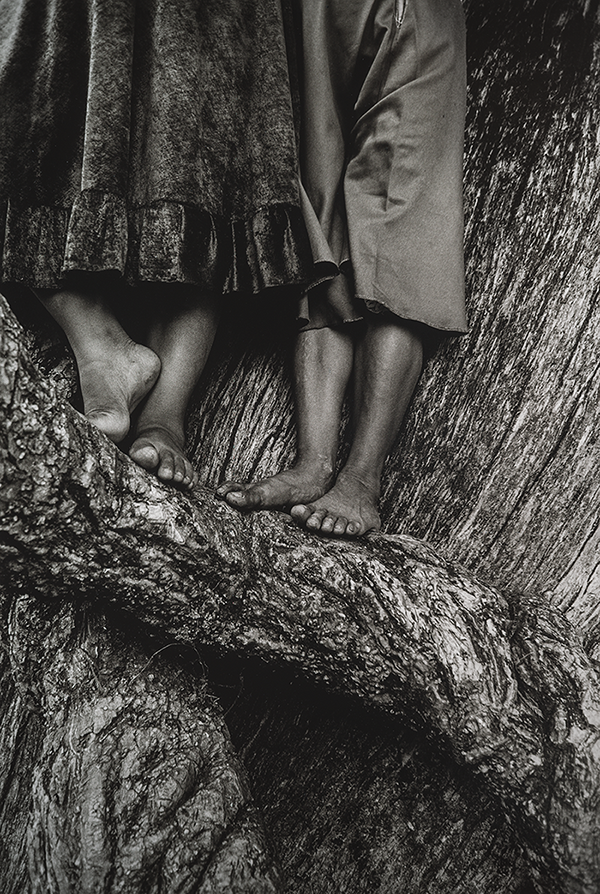

For the past 50 years, Graciela Iturbide (b. 1942, Mexico City) has produced majestic, powerful, and sometimes visceral images of her native Mexico. One of the most influential contemporary photographers of Latin America, Iturbide elevates ordinary observation into personal and lyrical art. Her signature black-and-white gelatin silver prints present nuanced insights into the communities she photographs, revealing her own journey to understand her homeland and the world.

Opening at NMWA on February 28, Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico is the artist’s most extensive U.S. exhibition in more than two decades. The monumental survey is organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and comprises 140 poetic photographs bearing witness to the rich and complex culture of the artist’s homeland. Including images from 1969 through 2007, the exhibition encompasses compelling portrayals of indigenous and urban women, explorations of symbolism in nature and rituals, and haunting photographs of personal items left after the death of Frida Kahlo.

Exhibition Themes

The exhibition is organized into nine sections that illustrate Mexico as a rich tapestry of cultures, through daily rituals, social inequalities, and the coexistence of tradition and modernity. In Early Work, Iturbide’s attraction to unusual urban geometries and her eye for the unexpected is apparent. Three sections focus on her photographs of indigenous societies: Juchitán, home to the matriarchal society of the Zapotec people; the Seri, who live in a transitioning culture in the Sonoran Desert in northwestern Mexico; and La Mixteca, chronicling the Oaxacan herding community’s annual goat slaughter festival.

The Fiestas, Death, and Birds sections further demonstrate the artist’s deep awareness of cultural symbols. Beginning in the 1970s, Iturbide traveled throughout Mexico recording a variety of lavish fiestas, which incorporate elaborate costumes, ceremonies, and spectacles. Early in her career, following the tragic loss of her six-year-old daughter, Iturbide described her need to photograph the deaths of others as a way to come to terms with her own pain. Birds, too, became a vehicle for her spiritual and emotional journey.

In the Botanical Garden section, Iturbide’s photographs of Mexican flora and fauna are rendered with as much as sensitivity as her images of people. In 1998, Iturbide photographed the Ethnobotanical Garden of Oaxaca, which tells the story of the relationship between the people of Oaxaca and the region’s native plant life—the cactus, in particular. In Mexico, cacti are used on a daily basis for food, alcohol and medicine, as well as being a national symbol.

The final section, Frida’s Bathroom, refers to Iturbide’s 2005 commission to photograph Frida Kahlo’s belongings in the painter’s bathroom at Casa Azul, where Kahlo was born and died. Iturbide’s stark photographs provide an emotional narrative of the intimate space. Her images focus on objects that underscored Kahlo’s chronic illness and physical pain. Iturbide relates to Kahlo personally, as a fellow Mexican woman artist who has used her art to grapple with the hardships and tragedies of life.

Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico is on view through May 25, 2020.