In the late 1980s, quilt-lovers and feminists Jane Benson and Nancy Olsen approached Euphrat Gallery director Jan Rindfleisch with an idea for an exhibition on political quilts. After two years of research, the women published The Power of Cloth: Political Quilts 1845–1986 to accompany the exhibition. In the book, the authors state that while men were allowed to vote and participate fully in political events, some women took to quilting as a means of expressing their own political alliances and opinions.

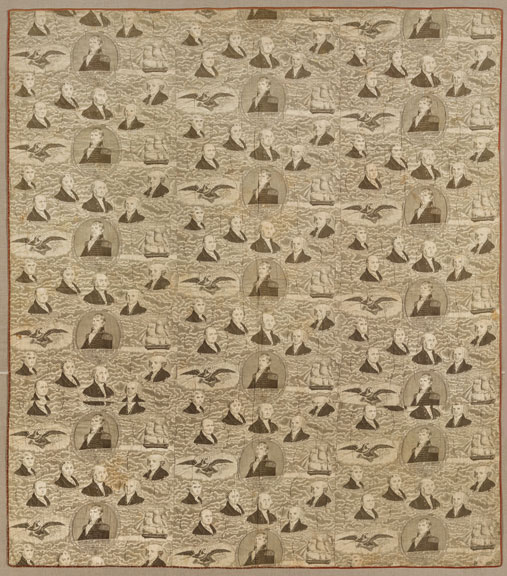

For example, Whole Cloth Quilt, ca. 1830s, uses a special cotton fabric that depicts the portraits of the first seven presidents. The inclusion of the phrase “Magnanimous in Peace, Victorious in War” beneath Andrew Jackson’s portrait suggests that the quilter was his strong supporter. However, political positions were usually not so overtly expressed in quilts, and women relied on symbolic imagery to state their opinions.

Medallion Quilt, ca. 1830, depicts an image of an eagle, derived from the American Bald Eagle, which was adopted as the great seal of the United States in 1782. As Benson and Olsen state, the eagle became a popular national symbol for “strength, power, and keenness of vision,” which made them and other patriotic icons prevalent in the first half of the 19th century due to the War of 1812 and the territorial expansion to the west. Therefore, both male and female viewers would have quickly understood the quilter’s nationalistic stance.

Yet there were also many instances when men were oblivious to the female subculture around quilting. Women found ways to exert power and take ownership of the practice of quilting, one of which was by naming patterns in such a way that their significance was only understood by fellow quilters. In fact, names of quilt patterns, much like titles of artworks, had the power to transform a seemingly traditional quilt into a highly politicized one. Benson and Olsen give a few examples of the way changing the names of quilting patterns can, in turn, change their connotations. For instance, in response to the issue of slavery, quilters changed the name of the “Jacob’s Ladder” pattern to “Underground Railroad” (though this has been disputed by other researchers, who say that the pattern did not appear until after the Civil War), and the “Whig Rose” pattern changed to “Radical Rose” when a black circle was sewn into the center of the flower.

In a sense, this “secret language” of quilting was a way for women to compensate for their lack of political representation. While men were able to express their political stances in the public sphere, women did the same thing, albeit quietly, as they stitched their views into the very fabric of history.