“These are my favorites,” said Amy Sherald, gesturing to two of her paintings on view in NMWA’s collection galleries. “It was a relief to walk in here and see these. There’s absolutely nothing that I would fix because I had all the time in the world.” After winning first prize in the 2016 Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition for the National Portrait Gallery, the Baltimore-based artist keeps a busy schedule. During an Artists in Conversation program at NMWA on May 9, Sherald shared her sources of inspiration and what she hopes viewers will take away from her work.

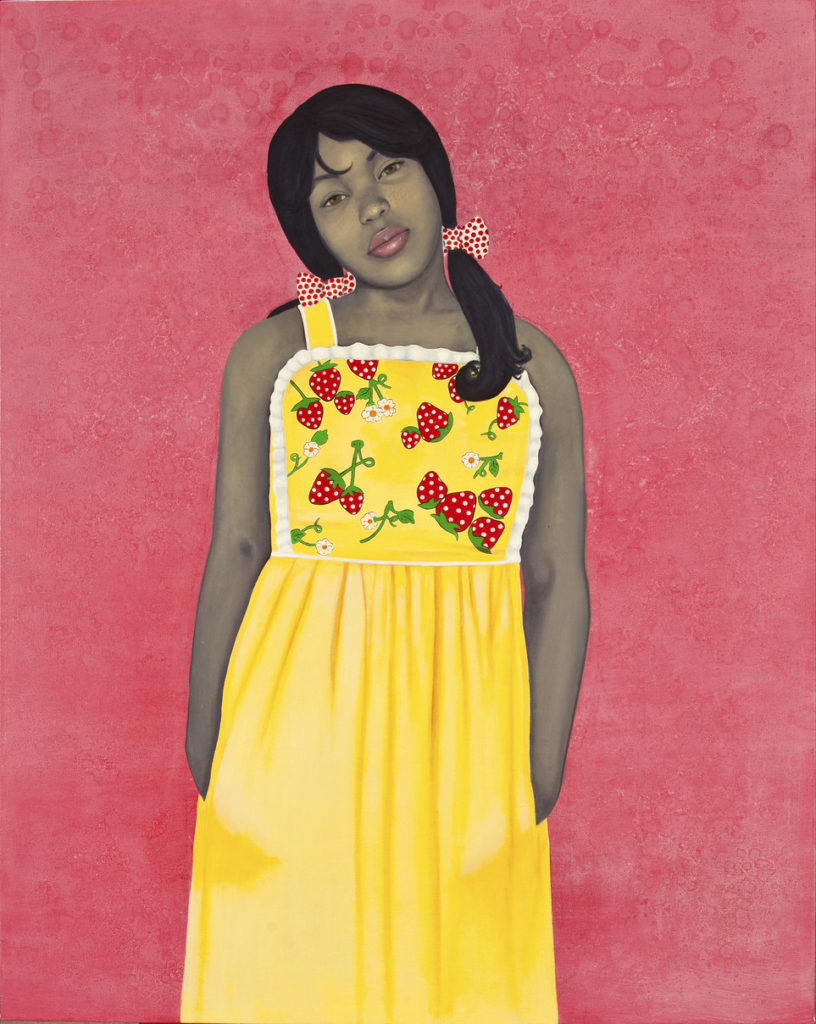

They Call Me Redbone but I’d Rather Be Strawberry Shortcake (2009) relates to Sherald’s life in Columbus, Georgia. “Once I moved to Baltimore I realized no one called me a ‘redbone,’” explained Sherald. “If you don’t know what a ‘redbone’ is…it refers to someone who is supposed to be of Native American, African, and European descent. So, in the South it was very race conscious. . . . My basketball coach called me ‘redbone,’ which I really didn’t mind. And then there were other people who I didn’t know who called me ‘redbone’…and I didn’t like it so much.”

Sherald explained her personal connection to the subject of It Made Sense…Mostly in Her Mind (2011), portraying a horseback rider holding a children’s toy unicorn. “I went to an equestrian riding camp when I was an adolescent,” said Sherald, who later developed the idea for the painting after seeing her friend’s mother do dressage. Sherald asked her friend, Christina, to model for the painting because she embodied the sophistication Sherald wanted to capture.

Both paintings are displayed on the same gallery wall as Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky (1937). “Frida Kahlo was one of my inspirations,” said Sherald. “When I changed my major from pre-med to painting, I had these ideas of painting a lot of the same things she did. I was talking to my art teacher Arturo Lindsay and he said, ‘look up Frida Kahlo.’” Sherald added, “I’m honored, to say the least.”

When discussing the impact of her paintings, Sherald told attendees, “I received emails from all kinds of people that see themselves in this work, and that’s really important too.” Sherald noted, “When you walk through a space like [the museum] you don’t always see this [gesturing to the figures in her paintings]. For me, this became really important, interjecting images of the underrepresented in the dominant circle narrative and making work that I felt would resonate in a way that art history can’t be told without it. . . . I consider myself an American Realist, maybe with a post-modern flare.”

Visit the museum to see Sherald’s paintings in person. Stay tuned about future programs through the online calendar and by signing up for e-news.