In celebration of NMWA’s 30th anniversary, and inspired by the museum’s focus on contemporary women artists as catalysts for change, Revival illuminates how women working in sculpture, photography, and video use spectacle and scale for expressive effect.

Charlotte Gyllenhammar (b. 1963, Gothenburg, Sweden)

Although Charlotte Gyllenhammar studied painting in art school, her work consists primarily of film and three-dimensional installations. Even after this shift in medium, a painterly sensibility continues to inform her work. Gyllenhammar often incorporates projections and sculptures to create spatial complexity. Her work invites the viewer into an emotionally charged dialogue through intense contrast between images. By employing the surreal, she masks the familiar in an unfamiliar guise, calling the viewer’s concepts of normalcy into question. Her pieces frequently engage with themes such as inversion, sight, and loss of innocence.

The Artist’s Voice:

“My sculptures are sort of falling, and falling forward, or throwing themselves, and hanging, and hovering, and falling, so I think I have that kind of dynamic—these poles of the more passive, implicit and the more active, explicit.”

“I’m fascinated by that sort of living, sleeping, breathing, resting, and the sort of ultimate point, death. . . . And you don’t know when, you don’t know how, but we know that. But I find it very hard to accept that we are going to die. That’s kind of an unbearable thought that I tried to get used to.”—Charlotte Gyllenhammar, interview in The Parlor.

Revival Highlight:

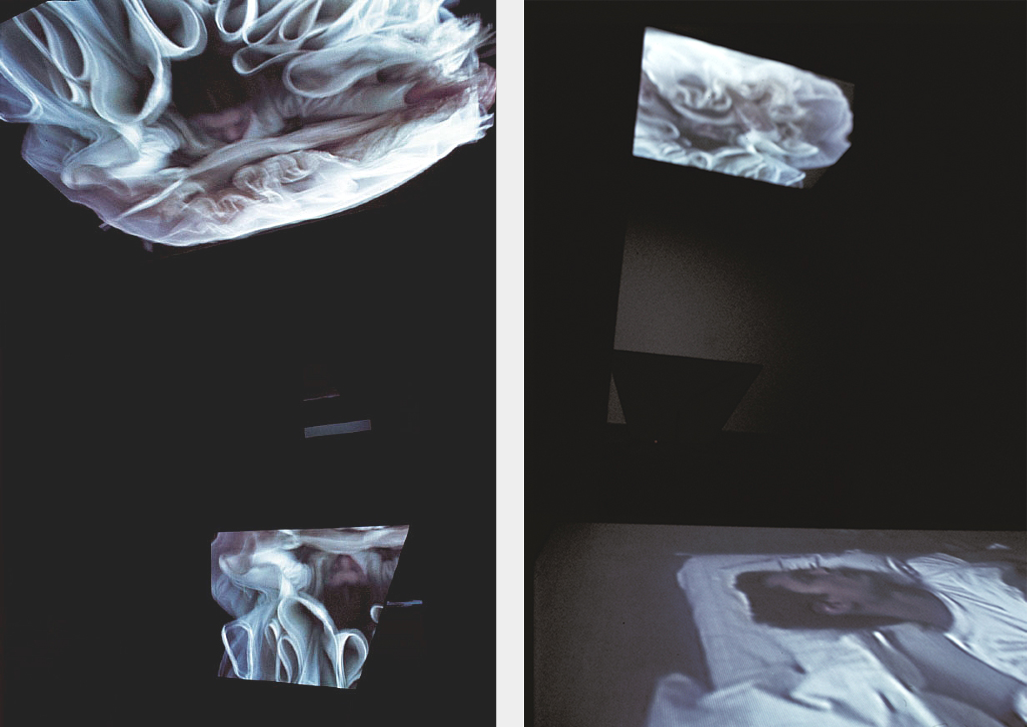

Unrest and repose become bedfellows in Charlotte Gyllenhammar’s Fall (1999), a two-screen video installation featured in Revival. Projected on the ceiling, the video shows a woman hanging upside down, her extravagant dress billowing around her. On the floor another projection shows two men sleeping in a narrow bed. Their occasional movement seems less like an acknowledgement of her frustrated struggles and more like a mundane nighttime reflex.

Rather than employ traditional narratives, Gyllenhammar seeks meaning in contradiction and contrasting visions. While the woman appears trapped by her suspension, the unconventional angle makes it seems as though she is floating freely. Her solitary struggle contrasts with the men’s peaceful companionship, lending a sense of complicity to their rest. Yet even as this unawareness becomes an accomplice in her discomfort, their innocence shields them from even acknowledging her.

Gyllenhammar’s fascination with sight and seeing comes into play as well. The screens function as windows, allowing viewers to observe the characters like voyeurs. What visitors see reverses the dynamics of vulnerability. Although the hanging woman appears vulnerable through the unwilling exposure of her body, she retains agency in the camera’s concealment of that exposure. The men slumber in a safer environment, yet suffer complete exposure to the audience, completely open and vulnerable in their lack of awareness. Attentive to the unseen as well as the seen, Gyllenhammar crafts a scene that leaves viewers hanging, unsettled but ultimately intrigued.

Visit the museum and explore Revival, on view through September 10, 2017.