In celebration of NMWA’s 30th anniversary, and inspired by the museum’s focus on contemporary women artists as catalysts for change, Revival illuminates how women working in sculpture, photography, and video use spectacle and scale for expressive effect.

Cathy de Monchaux (b. 1960, London, England)

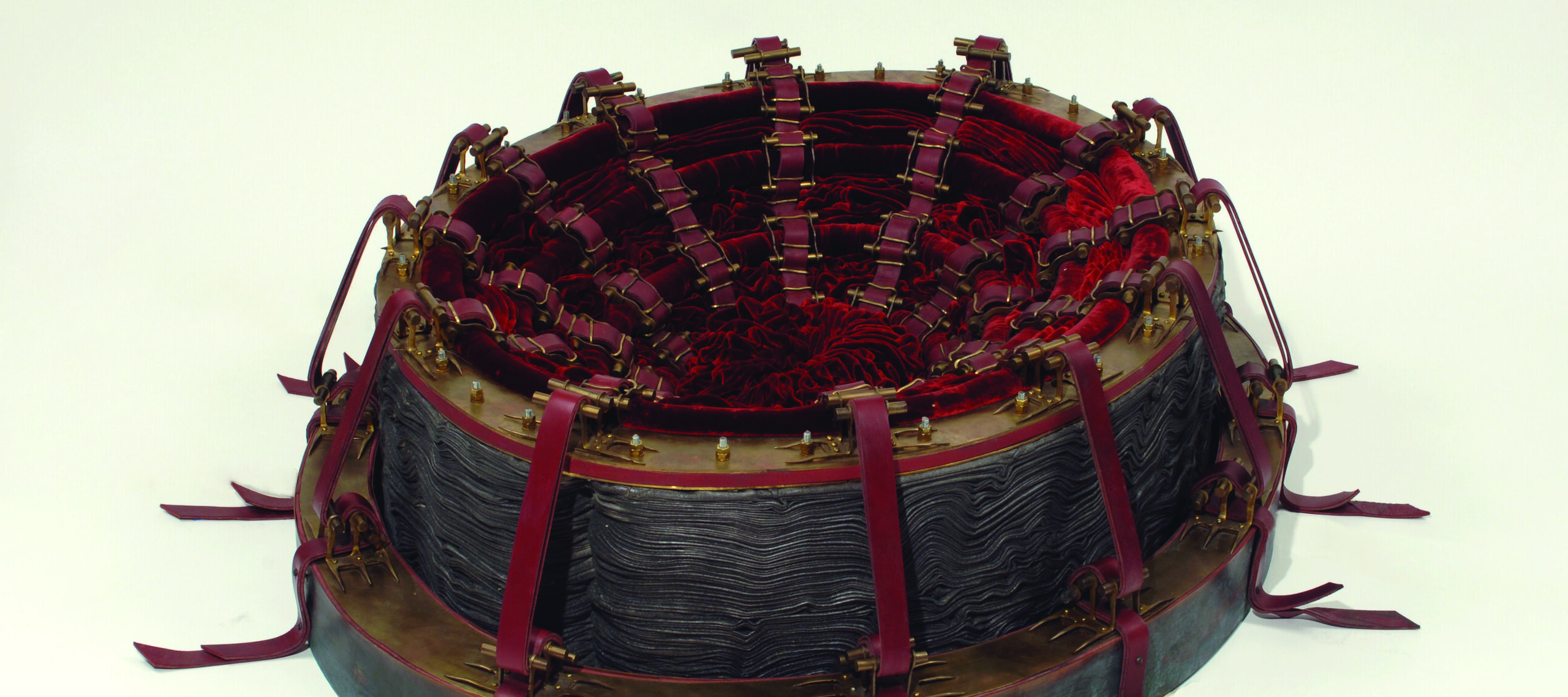

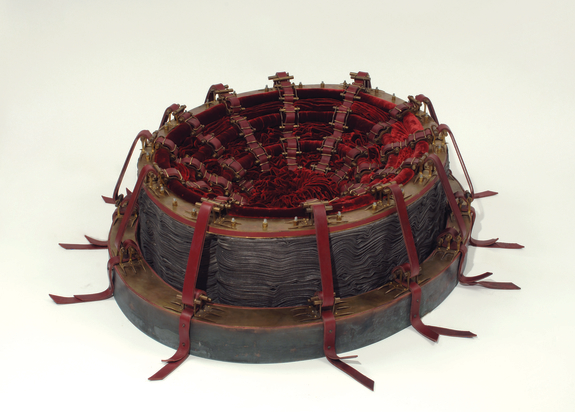

Although at first glance Cathy de Monchaux’s work seems to mimic bodily forms, closer inspection reveals an act of fusion at work. With obsessive attention to detail, de Monchaux joins soft, vulnerable, seemingly organic components with sharp metallic points or hooks. The marriage of paradoxical materials elicits contradictory feelings from her audience. While the flesh-like material evokes an uncomfortable recognition, the cruel, protruding metals inspire an awed fear; if the soft, voluptuous shapes summon lust, the jutting spikes repulse empathy.

The Artist’s Voice:

“I use the erotic as a metaphor for angst. A lot of people’s angst comes from how they relate to other human beings, and a lot of that is to do with attraction and repulsion. Every relationship becomes fraught after the first burst of enthusiasm, and I suppose I use the whole erotic thing as a metaphor for that fraught-ness.”—Cathy de Monchaux, in an interview with The Telegraph

Revival Highlight:

Rather than rely on representation, de Monchaux uses the power of suggestion to draw in her viewer, promising manifold possibilities within a singular form. Her luxurious wall pieces Don’t Touch My Waist (1998) and Clearing the Tracks Before They Appear (1994) lure the viewer in with appearances evocative of sumptuous, feminine clothing. But the former’s jagged hooks and the latter’s subtle metal teeth keep any would-be-wearers at bay, promising pain in place of any decorative pleasure that might otherwise be derived. Blending pain and pleasure, distance and proximity, injury and protection, de Monchaux simultaneously evokes the joys and the fears of femininity, revealing how eroticism encompasses the whole spectrum of danger and safety.

A floor sculpture featured in Revival, Red (1999), contains fewer elements of dangerous elegance, opting instead for a more subtle approach. It appears less threatening and direct than both hanging works, lacking sharp blades or hooks. Instead the work contains a cascading center that blossoms into tender, fleshy velvet folds. But for all its sumptuousness, the central structure seems contained within the base, suggesting constriction that the surrounding belts only complement. Red’s foreboding presence underscores de Monchaux’s capacity for creating disquieting work in all shapes and forms.

Visit the museum and explore Revival, on view through September 10, 2017.