In celebration of NMWA’s 30th anniversary, and inspired by the museum’s focus on contemporary women artists as catalysts for change, Revival illuminates how women working in sculpture, photography, and video use spectacle and scale for expressive effect.

Maria Marshall (b. 1966, Bombay, India)

Although Maria Marshall began her career as a sculptor, her fascination with film led her to explore the short video as an art form. Marshall credits filmmakers with inspiring the lean visual narratives she so adeptly maneuvers. Despite frequently featuring her own children in fantasies inspired by parental fear, her video works and photography never quite fall into the category of autobiography. They straddle the division between personal and universal, serving as “concise metaphors” for the fear lurking in each viewer’s subconscious. Marshall’s surreal images promise narrative but deliver further intrigue. The often dreamlike atmosphere of her photos and video works hint at a setting where the imaginary blends with reality, and assumptions clash with truth.

The Artist’s Voice:

“My work is very constructed, and I have learned a great deal from filmmakers in this regard. . . . I also look for clean visual information. The language of film is full to the brim of seduction. I like beauty and I like to draw in the viewer, so I get very moved by certain sequences.”

“I purposefully try to create confusion, to muddle the boundaries. . . . I try to make films that go directly to the psyche, that probe it and manipulate it.”—Maria Marshall, in an interview published in Maria Marshall (modo Verlag, 2002)

Revival Highlight:

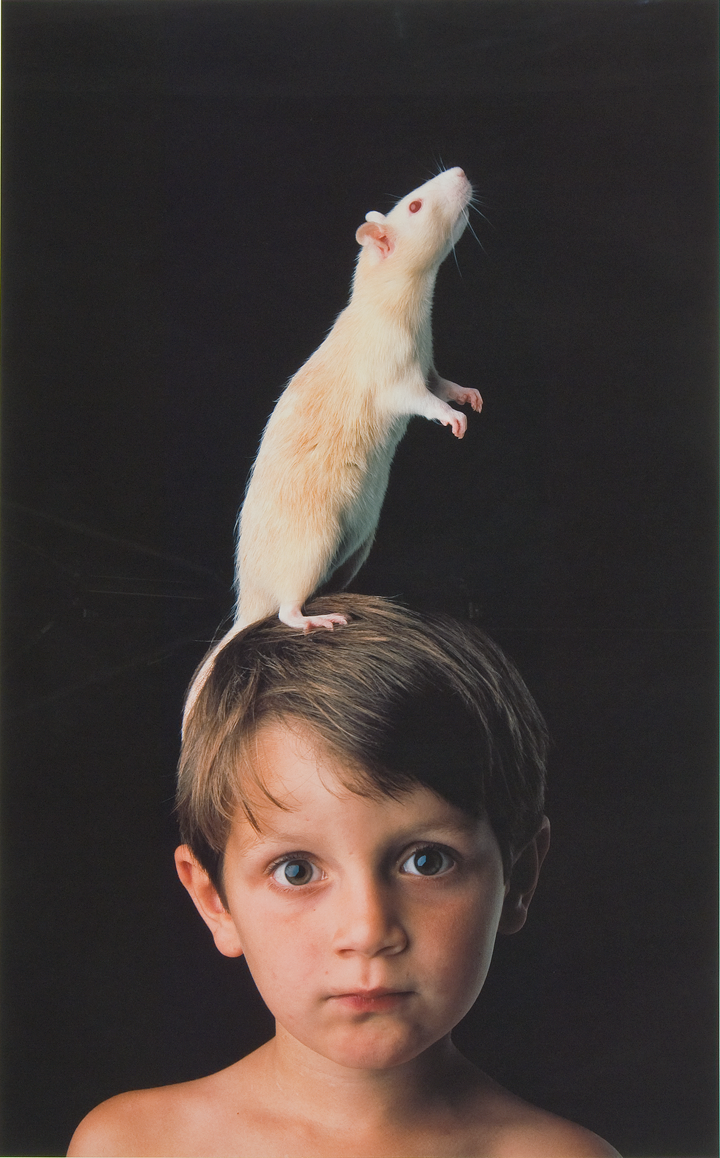

According to Marshall, her oeuvre stems from fear. Her works featured in Revival are no exception. Striking images of a toddler smoking, a boy in a fur coat, and a rat standing on a child’s head not only catch the viewer’s eye, but may also elicit outrage or concern. Through the portrayal of her own children in apparent moments of endangerment, Marshall plays on traditional conceptions of children as innocent or passive, asserting their personhood with unconventional tactics. Even as she plays on the audience’s expectations, however, she admits her own concerns as a mother unable to protect her children from the harsh realities of the outside world.

Future Perfect (1998) further reflects these complex feelings about growing children. While an adult might scrutinize rats due to the fraught associations they summon, the boy seems accepting of the live rat standing on his head. Whether this reveals his trusting, childish innocence, or a mature acceptance beyond what adults expect, Marshall reveals an incongruity between children and their parents, a dissonance that forms the core of her work in expressing anxiety while acknowledging a parent’s tendency to project. The title of the work alludes to the grammatical tense for a completed future action, hinting at an ambiguous but foregone conclusion.

Visit the museum and explore Revival, on view through September 10, 2017.