One of the most influential contemporary photographers of Latin America, Graciela Iturbide has produced majestic and powerful images of her native Mexico for the past 50 years. Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico is the artist’s most extensive U.S. exhibition in more than two decades, comprising 140 black-and-white prints that reveal the artist’s own journey to understand her homeland and the world.

In The Labyrinth of Solitude (1950), renowned Mexican writer Octavio Paz reflected on Mexico’s national attitude toward death. “The Mexican frequents it, jokes about it, caresses it, sleeps with it, celebrates it…he confronts it face to face with patience, disdain, or irony.” True to this sentiment, in her photographs, Graciela Iturbide (b. 1942) steadily confronts what she calls “Mexico’s death fantasy” as it appears in the street, at festivals, and in the cemetery.

Iturbide’s photographs of death’s imagery connect to her own search for ritual and meaning, as well as to her faith in the power of photography as therapy. Her images are symbolic explorations of loss and mourning that represent and relieve her own grappling with death.

Disguises, worn by the living, are a traditional part of some funerary processions in Chalma. In Peregrinación (Procession) (1984), masked figures surround and support a man dressed as a skeleton. In the background, a baby in white may represent an angel—an indication of life and hope amid the chaos of the procession. The photograph represents the somewhat comic, performative ambiance of the festivities.

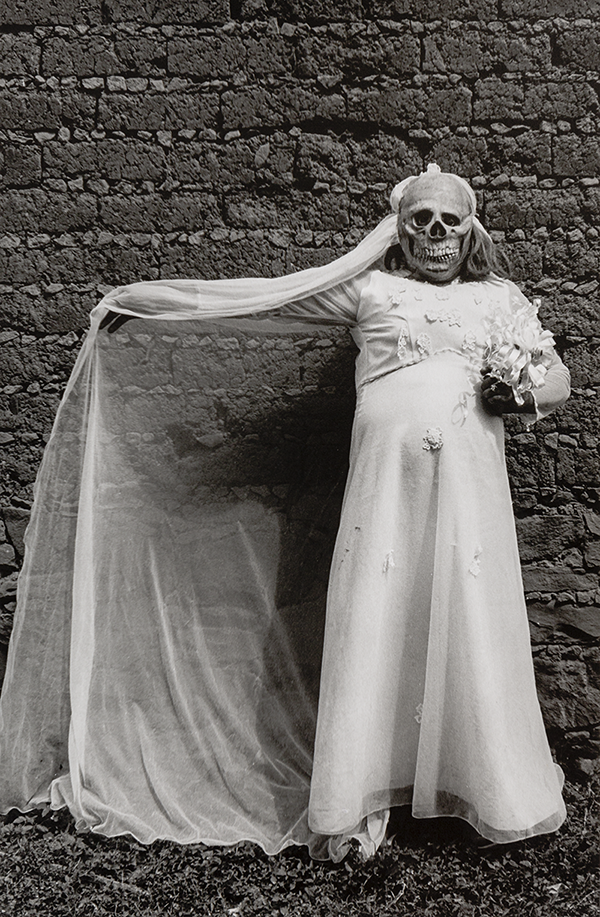

In Novia Muerte (Death Bride) (1990), a man dressed as a bride wears a wig, a death mask, and holds a bouquet of flowers. This costume may also be viewed as comedic, but deeper layers of meaning proliferate. His pose, with one arm out to the side, may be an invitation or a reminder of the presence, absence, or death of a marital partner. A dark shadow covers part of the translucent veil that falls from the “bride’s” arm to the ground.

Iturbide herself is no stranger to death; she tragically lost her six-year-old daughter and subsequently became obsessed with photographing the funerals of other deceased children. While photographing one funeral in 1978, Iturbide came across a decomposing corpse on a cemetery walkway. In an interview with the Guardian, she explained, “I felt as if death had appeared and said, ‘That’s enough! Don’t keep living your suffering in this way. Stop it!’”

That day, Iturbide also photographed Pájaros (Birds) (1978), in which birds appear to emerge from an ominous cloud above the cemetery. To Iturbide, birds represent solitude, freedom, and independence. In Pájaros en el poste, Carretera (Birds on the Post, Highway) (1990), she captures a large flock surrounding a telephone pole in the form of a cross; this photograph poetically communicates the fusion of the sacred and secular. In ¿Ojos para volar? (Eyes to Fly With?) (1991), she portrays herself holding one dead bird and one live bird. She places them with their heads in front of her eyes as a metaphor for the abilities to see, to know, to make known, to photograph, and to fly.

*Unless otherwise noted, information is adapted from Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico: Photographs, by Kristen Gresh, with an essay by Guillermo Sheridan.