One of the most influential contemporary photographers of Latin America, Graciela Iturbide has produced majestic and powerful images of her native Mexico for the past 50 years. Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico is the artist’s most extensive U.S. exhibition in more than two decades, comprising 140 black-and-white prints that reveal the artist’s own journey to understand her homeland and the world.

In 2005, just over 50 years after Frida Kahlo’s death, Graciela Iturbide (b. 1942) was commissioned to photograph the contents of the artist’s bathroom at her home, Casa Azul, open to the public as the Frida Kahlo Museum. The room had been locked for decades after Kahlo’s mourning husband, Diego Rivera, entombed 300 of her personal belongings there and ordered the space sealed for 15 years following his own death. Iturbide’s photographs construct an intimate portrait of Kahlo’s personal life through her belongings. Stark images of corsets, crutches, painkillers, and prosthetics convey a venerated life of suffering, resilience, and determination. Yet the photographs are more than documentary. In one intimate image, Iturbide responds, and pays homage, to Kahlo’s cultural legacy, creating an artistic dialogue between the two women.

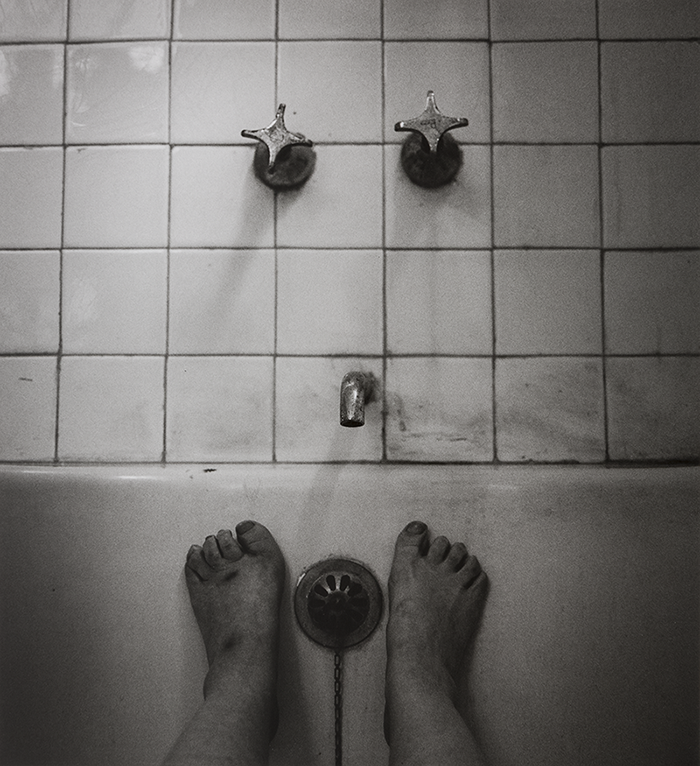

Of all the images in Iturbide’s “Frida’s Bathroom” series, there is just one self-portrait; it evokes Kahlo’s famous painting What the Water Gave Me (Lo que el agua me dio) (1938). In this photograph, Iturbide rests her feet against the side of the artist’s bathtub. This placement mimics Kahlo’s painting of her own feet partially submerged in a tub, her right foot bleeding, a collage of surreal images floating in the bathwater. By recalling the painting, Iturbide acknowledges Kahlo’s art historical precedence and the importance of this private space. Iturbide portrays her own suffering in the self-portrait by revealing, in her signature photographic style, her pained feet after a recent operation. The profound image conveys the experiences of both Kahlo and Iturbide, connected across 50 years.

Other objects in Kahlo’s bathroom included sunglasses, nail polish, shoes, political imagery, and clothing, however, Iturbide primarily focused her series on those objects that related to the artist’s pain. This choice echoes themes that have surfaced in Iturbide’s own work: death on both personal and cultural levels; illness, including a focus on ailing cacti; and ritual, including animal slaughter. Iturbide does not turn away from pain, but instead looks unflinchingly at it. In one of Iturbide’s photographs, Kahlo’s hospital gown hangs against the bathroom’s tiled wall, marked in many dark stains. In black and white, it is impossible to tell if the stains are blood, evidence of her suffering, or paint, evidence of her salvation.

As Kahlo’s life, work, and legacy have grown to mythic status over the years, Iturbide has said that she is not a “Frida-maniac.” However, the intense experience of photographing the artist’s intimate, long-shuttered bathroom helped Iturbide learn that Kahlo “was a marvelous woman who contended with a lot of pain…I feel like I got to know her better.”

*Unless otherwise noted, information is adapted from Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico: Photographs, by Kristen Gresh, with an essay by Guillermo Sheridan.