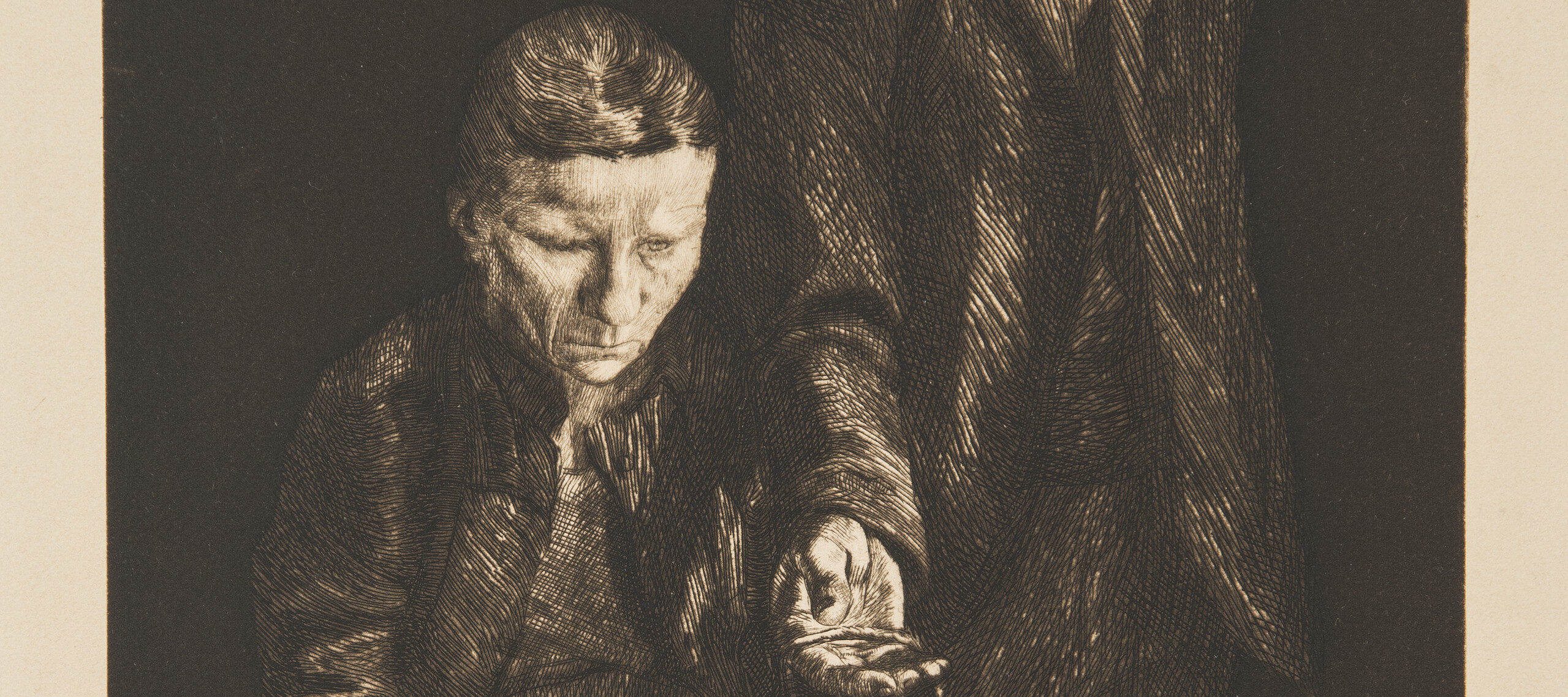

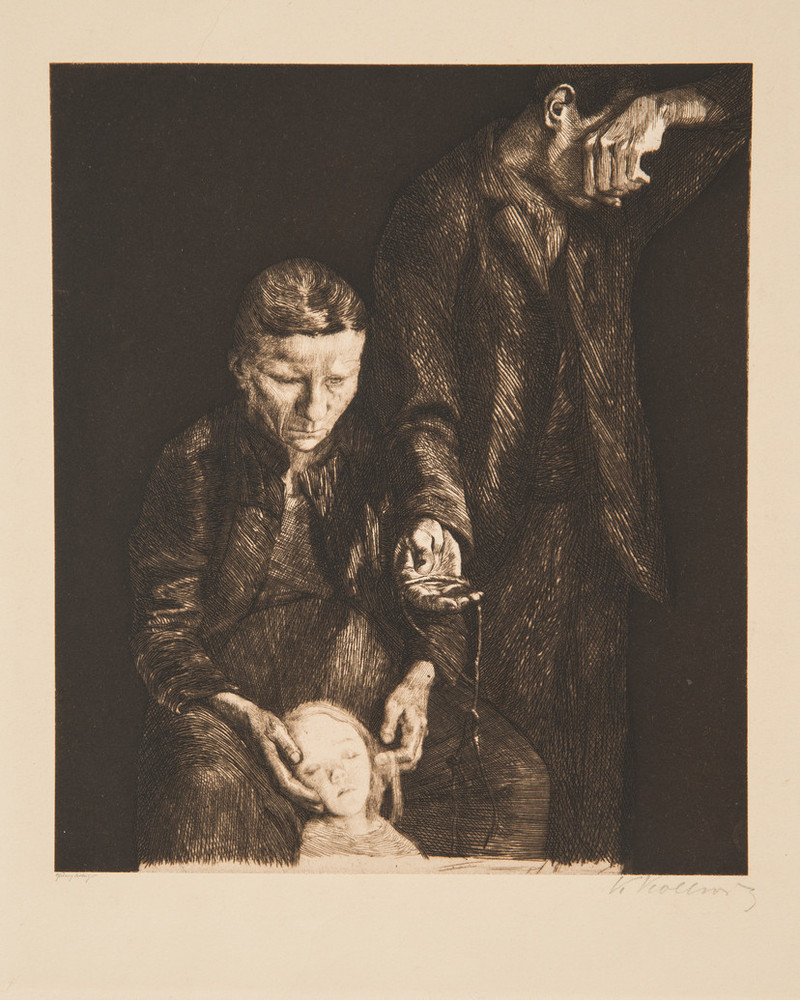

The Downtrodden (1900), an etching by German printmaker and sculptor Käthe Kollwitz, is back on view in NMWA’s exhibition galleries. This work by Kollwitz—whose art was labeled “degenerate” by the Nazis—calls to mind recent news such as the reappearance of looted art, discovered at the residence of the son of a Nazi-connected art dealer, as well as a current exhibition at the Neue Galerie that includes many “degenerate” works displayed by the Nazis. The media has consistently focused on the resurfacing of paintings by canonical artists such as Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Claude Monet, but has done little to explain the Nazis’ complex treatment of and interaction with artists.

Picasso and Matisse were among the group of artists targeted by the Third Reich, though German artists such as Käthe Kollwitz also had their artwork labeled as “degenerate” by the Nazis. The term defined any artwork seen as “un-German”: art the Nazis perceived as foreign, elitist, Jewish, or Communistic in appearance. “Degenerate” art was removed from German museums in the 1930s and many works ended up in the Nazis’ notorious Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich in 1937. There is evidence that Kollwitz’s works appeared in the Munich exhibition, though it seems Kollwitz’s art was removed from the show in 1938 upon arrival in Berlin.¹

A bizarre aspect of Kollwitz’s initial inclusion in Degenerate Art is that the Nazis appropriated her work for their own propagandistic uses on multiple occasions. As recalled by Kollwitz’s friend and fellow artist, Otto Nagel, the Nazis reprinted her series Hunger, claiming the images showed victims of communism, and reproduced Kollwitz’s print Bread! without crediting the artist: they gave the image a fake signature, St. Frank.²

Works such as The Downtrodden give clues to the Nazis’ contradictory behavior. The etching shows a family in the midst of hardship: a sorrowful mother holds her deceased child, while the father turns away from the scene, his forearm concealing his face from the viewer. This scene, coupled with the stark, monochromatic medium of etching, gives the image a universal quality: it could take place anywhere at any time. Though the Nazis did not reproduce The Downtrodden, nor did it appear in Degenerate Art, its universal quality is typical of Kollwitz’s body of work. This universality allowed the Nazis to remove her works from their original context to serve their Fascist agenda. Why the Nazis decided to label Kollwitz “degenerate,” only to remove her from this degenerate status in 1938, however, is more of a mystery. Evidence points to her stylistic similarity to the Expressionist movement and her sympathy for the Communist party. Scholars’ ambivalence toward Kollwitz’s fate at the hands of the Nazis proves the need for greater exploration of the final years of Kollwitz’s career, especially the Nazis’ condemnation and appropriation of her work.

Notes:

1. Christoph Zuschlag, “An Educational Exhibition: Precursors of Degenerate Art and Its Individual Venues,” in “Degenerate Art”: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany, ed. Stephanie Barron (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1991), 92.

2. Otto Nagel, Käthe Kollwitz, trans. Stella Humphries (Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society Ltd., 1971), 81.