Gego (1912–94) was born Gertrud Goldschmidt in Hamburg, Germany, to a Jewish banking family. Her family fled Nazi Germany for England in 1939, but Gego stayed behind for a few months to complete her degrees in architecture and engineering at a technical university in Stuttgart.

She joined her family in England after shutting down the family business and dispersing their remaining possessions, dropping the keys to their home in a river. However, unable to gain resident status in England, she immigrated to Venezuela later the same year. There she combined the first syllable of her first and last names, “Gego,” to ease pronunciation in her new country. According to the Jewish Women’s online Archive, Gego never publicly spoke about her experience as a Jew in Nazi Germany. She eventually became a citizen of Venezuela.

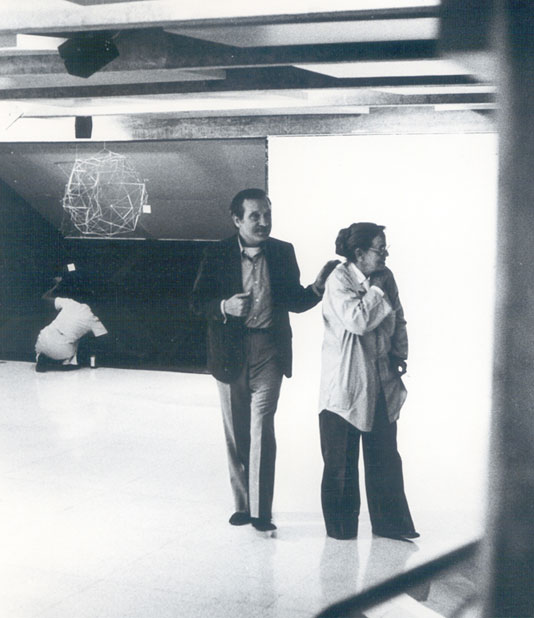

Gego worked on architecture and design projects in her first decade in Venezuela. She married a fellow German immigrant, Ernst Gunz, with whom she had two children. They divorced in 1951. The following year, she met artist Gerd Leufert (1914–98), who became her lifelong companion. Leufert encouraged her to focus completely on her art, though she retained a keen awareness of space from her architectural training.

Gego first worked at the Tamarind Institute, then located in Los Angeles, during a 1963 trip to the United Stateswith Leufert. She returned for a two-month Tamarind fellowship in November and December of 1966, when she completed the two works in NMWA’s exhibition, as well as many other prints. The two works on view in Pressing Ideas stand out as the only artworks that do not hang on the walls: Gego created two book-like sets of prints, one foldable and the other a more “traditional” book with pages. According to Tamarind’s archives*, each work was printed as one sheet and torn or folded to Gego’s specifications after printing.

Critic Robert Shuster stated in a review of a 2007 Gego exhibition, “Ah, humble line! …Gego was your champion.” The works in Pressing Ideas are no exception. Lines (1966) is completely dedicated to linear experimentation. A sea of wavering horizontal lines fills the left page, broken by a harsh, bold, vertical zig-zag. Gego allows more space between the lines on the right page. These appear almost as waves, with two bent lines like an open drawbridge at the top. Of course, this is only one set of pages in Gego’s lithographic book, which alternates between two red and two gray pages.

Untitled (1966) is a multi-panel, folded print, intended to be displayed upright. Documentation from Tamarind compares the display of this work to that of a Japanese screen. Bold yellow stripes line the top of most panels, in contrast with delicate, light gray and barely-visible white lines beneath. The print’s irregularly spaced folds add a third dimension of linear patterning. Gego achieves a high level of precision and detail in both Untitled and Lines, demonstrating mastery of the subtleties of the medium of lithography. Tamarind’s worksheet on Gego’s fellowship states, “In her lithographs, intuitive in approach and direct in appearance, line builds into patterns that involve the viewer in the movement and rhythm of linear structure.”

Gego was also working in other mediums at this time. She called her hanging wire works “dibujos sin papel,” or “drawings without paper.” Don’t label these works “sculpture,” however. She wrote, “Sculpture: three-dimensional forms of solid material. NEVER what I do!” Gego’s twisting, delicate wire forms activate void and shadow as part of the artwork. It is easy to see Gego’s drawings on paper, in the style of her work at Tamarind, come alive in space in these hanging works.

Gego’s art resists labeling and categorization in traditional terms of artistic movements and styles. She achieved quite original compositions both on paper and in three dimensions. Her work requires careful, close-up viewing that cannot be accurately conveyed in a blog post! Don’t miss Gego’s prints in the Pressing Ideas exhibition, on view through October 2. For more information on Gego, particularly on her later career, please visit the website of the Fundación Gego.

*Many thanks to Tamarind Institute director Marjorie Devon for access to Gego’s 1966 Tamarind Fellowship information sheet!